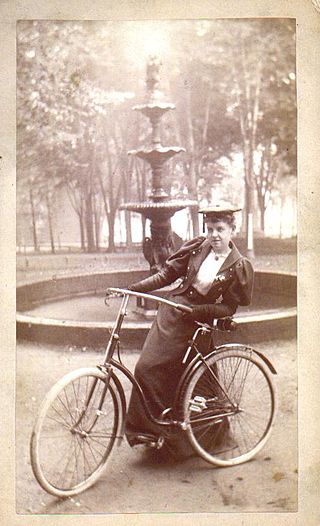

We love and have always loved the ladies who ride — in this case a lady of the 1890s. (Photo: Wiki Commons)

Get your spokes aligned by reading part I and part II of this series “Astride Loft Wheels.”

In the late 1880s, after long efforts by manufacturers to design a less hazardous machine, the “safety” bicycle hit American markets. With two wheels of the same size and chain-driven rear crank, the new safeties were easier to ride and far less dangerous than the “ordinaries.”[16] However, into the 1890s many riders clung to their high-mount bicycles as superior in design. To ride as high a wheel as possible was not only a matter of gaining speed but one of pride and machismo as well as vantage point. Riding high over the crowd one could not only feel superior but see farther. And the attitude of many riders was that the risk in cycling was all part of the caché. To make cycling more safe, so some of them thought, was to take the fun out of it.

As an expensive and dangerous hobby, bicycling in these formative years was mainly a pursuit of the athletic young men of the upper classes. When Pope Manufacturing Company began selling high mounts 1879, twenty-five hundred bicycles were sold in the United States, one going to the New Orleans jeweler, A.M. Hill. An amateur athlete and member of the Young Men’s Gymnastic Club, Hill soon became the pioneer wheelman of the South. When he started cycling in 1879, there were only two other bicycles in the whole state of Louisiana.[17] Two years later, Hill organized New Orleans’ first bicycle club, with twenty members, at a meeting at his jewelry store at St. Charles and Commercial Alley.[18] This was the business Hill had started when he moved to New Orleans at the age of 19, in 1866.

Hill had grown up in Pennsylvania and been educated at the early public schools there known as “common schools.” He’d then gone on to Iron City Commercial College in Pittsburgh, the first business school in the United States, graduating at 15. After working for a few years for his brother in Louisville, Kentucky, the nineteen-year-old Hill moved to New Orleans and began a business making and repairing gold pens for the businessmen of downtown New Orleans. He lived above his shop at No. 86 St. Charles. Hill gradually expanded his business as a jeweler, and in 1882 bought out the jewelry store at Canal Street and St. Charles Avenue. He would eventually build it into one of the most successful jewelry businesses in the South.[19]

At the first meeting of the New Orleans Bicycle Club in 1881, Hill was, predictably, elected Captain.[20] (Although A.M. Hill served as Captain of the NOBC for only the first few years, he continued to be referred to as “Captain Hill” ever after.) The NOBC soon contracted to have a square of Canal Street paved with asphalt—some of the first in the city– to give the club a practice ground.[21] A man of pioneering mind, Hill was intent on promoting bicycling as not only an enjoyable sport but a means of practical transportation. As stated in the club’s charter, the object of the club was both mutual enjoyment among cyclists and the promotion of the bicycle as “a practicable and enjoyable aid to locomotion by the general public.”[22] In service to this aim the club made regular runs around the city and to the resorts on the outskirts, wearing uniforms and riding together in coordinated rows with enforced procedures for passing wagons and carriages on the street. Captain Hill’s NOBC, laboring against stigmas that had plagued the bicycle from its invention, sought to represent bicycling as a dignified occupation that could greatly serve the public weal.

In publicizing their activities, the NOBC often got help from its friends at the Daily Picayune. In 1881, the first year of the club, the Picayune reported a ride that Captain Hill made from downtown New Orleans, up Canal Street, and along Bayou St. John out to Spanish Fort, the resort area situated on the shores of Lake Pontchartrain. Marveling that he accomplished the six-mile ride in thirty-two minutes, the paper remarked, “This almost appears impossible, taking into consideration the state of the roads to Bayou Bridge.”[23] Doing what others deemed impossible was the nature of Captain Hill. With a receding hairline, swooping forehead and beaked nose, he was small in stature but made of grand ambition. By 1885, having made for himself both fortune and reputation as a businessman and active citizen, Hill was looking to make a name for himself as an adventurer. At the November meeting of the NOBC, he joined others in proposing a bicycle tour from New Orleans all the way to Boston, the site of the 1886 national meeting of the League of American Wheelmen.[24]

Inspiration for this proposal came from the famous bicycle tours being reported in newspapers at the time. Thomas Stevens was somewhere in Asia, having nearly completed his pioneering ride around the world. Outing, a popular sporting magazine, sponsored the trip and periodically published his travel accounts. His famous tales would later be published in the two-volume Around the World on a Bicycle. That year also, Karl Kron (Lyman Hotchkiss Bagg)[25] was touring the United States, gathering material for his book Ten Thousand Miles on a Bicycle, an amalgam of road guide, handbook, encyclopedia, and personal travel narrative that includes an eighteen-page biography of his dog, Curl, to whom the book is dedicated.[26] Such famous tours and publications stood as proof, according to Captain Hill, that “the cycle is a pleasant, safe, and economical method of journey.”[27] To travel by bicycle meant an entirely new kind of adventure, offering the rider far more independence than boat or rail but greater speed than walking. Besides being slow, to travel by foot carried a social stigma. According to Karl Kron, in the opening chapter of his book, “the very name of ‘tramp’ has come to carry with it the notion of something disreputable or dangerous.” But, “when the solitary wayfarer glides through the country on top of a bicycle . . . the whilom tramp is transformed into a personage of consequence and attractiveness. . .. All creatures who ever walked have wished that they might fly; and here is a flesh-and-blood man who can really hitch wings to his feet.”[28] So long as the roads were in cooperation, cycling was a means of transportation that was in its self a pleasure. To travel on foot was low and unfortunate; to travel by bicycle was noble and romantic. The bicycle traveler was able at once to break free from the confines of the crowd and establish himself as someone to be admired by it.

At the time he proposed the tour from New Orleans to Boston, Captain Hill had recently had a taste of long-distance bicycle travel. That July, after representing the Louisiana Division of the League of American Wheelmen as Chief Consul at the national meeting in Buffalo, New York, he had been the only southern participant in a northern long-distance touring club called the “Big Four” (so called because most of the members were from Chicago, Boston, Buffalo, and New York), a group of a hundred cyclists who rode from Buffalo to New York City in eleven days.[29] Cyclists were trying out the roads all over the northern part of the country, but so far no one had made a long-distance attempt across the South. Hill and Charlie Fairchild, who was at that time Captain of the NOBC, wrote letters to post-masters and well-known cyclists in cities along the planned route, inquiring as to distances and road conditions. From the responses they received, which turned out to be significantly on the rosy side of estimation, they determined that the trip would be more than possible. Originally, seven members of the club agreed to the tour. However, by the time of departure, only three remained game, the others bowing out over business and “other concerns,” possibly the fear that such a trip would prove miserably arduous if possible at all. Many of the New Orleans public were certain they’d never make it as far as Mobile, let alone Boston.[30]

Sources:

[16] Ibid, 225.

[17] Louisiana Cycling Club Spokes Scrapbook, 30.

[18] Daily Picayune. April 30, 1881. “A Bicycle Club.”

[19] Chamber of Commerce Book. Page 131.

[20] Daily Picayune. April 30, 1881.

[21] Ibid., July 16, 1881.

[22] Charter, By-Laws and Road Rules of the N.O. Bicycle Club. New Orleans: Hunter and Ginslinger, Printers, 48 Camp St. 1886. New Orleans Public Library Louisiana Division. Rare Vertical Files. Charters, No. 63

[23] Daily Picayune. “To Spanish Fort on a Bicycle.” May 3, 1881.

[24] Daily Picayune. “Bicycle to Boston.” July 23, 1886.

[25] Emil Rosenblatt, “Introduction.” In Ten Thousand Miles on a Bicycle. (reprint, New York: Emil Rosenblatt, 1982)

[26] Kron, “The Best of Bull-Dogs.” In Ten Thousand Miles on a Bicycle (1887; reprint , New York: Emil Rosenblatt, 1982), 407-425. Kron explains in a footnote that he had submitted this biography to a dozen magazines, and that it had been unanimously rejected. He offers a copy of the biography, along with the heliotype of the dog that appears in the front matter of the book, for twenty-five cents.

[27] Ibid.

[28] Karl Kron, Ten Thousand Miles on a Bicycle, 1.

[29] Ibid., June 26, 1885.

[30] Daily Picayune. “Bicycle to Boston.” July 23, 1886.

NOLAbeings

Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings

Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

Data corner: Adobe Suite (create a PDF, social media graphic, presentation, edit a photo and video

Data corner is where you go to work with analytics and top tech skills. It takes on everything from PERL and SQL to Canva and Sprout Social.

Data corner: Adobe Suite (create a PDF, social media graphic, presentation, edit a photo and video

Data corner is where you go to work with analytics and top tech skills. It takes on everything from PERL and SQL to Canva and Sprout Social.

[…] your spokes aligned by reading part I, part II, part III, part IV, part V, and part VI of Lacar Musgrove’s series “Astride Lofty […]

[…] your spokes aligned by reading part I, part II, part III, part IV, part V, part VI, and part VII of Lacar Musgrove’s series […]

[…] your spokes aligned by reading part I, part II, part III, and part IV of Lacar Musgrove’s series “Astride Lofty […]

[…] your spokes aligned by reading part I, part II, and part III of this series “Astride Lofty […]