Editors Note: The following series “Beyond the Beignets: A deeper look at New Orleans” is a week-long series curated by Rena Repenning as part of the Digital Research Internship Program in partnership with ViaNolaVie. The DRI Program is a Newcomb Institute technology initiative for undergraduate students combining technology skillsets, feminist leadership, and the digital humanities.

Because I live in New Orleans as a Tulane student, I often feel like a visitor instead of a resident because Tulane’s social life is disconnected from the city’s year-round residents. When creating Beyond the Beignets, I compiled 10 articles that articulated an often overlooked part of city life. Nestled in the heart of the famous French Quarter lies The Historic New Orleans Collection’s French Quarter exhibit. Although the museum’s name sounds as if it is simply a collection of artifacts, the HNOC is an immersive experience that allows visitors to immerse themselves in the French Quarter’s history. For further information visit https://www.hnoc.org/. This was originally published on May 3rd, 2019.

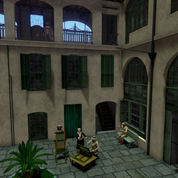

The Historic New Orleans Collection. (Photo courtesy of: The Historic New Orleans Collection)

If your impression of The Historic New Orleans Collection is that of a rather stodgy, somewhat academic museum that tells the history of the Gulf South and Lower Mississippi, THNOC’s newest Seignouret-Brulatour Building, focusing on the Vieux Carre, will shatter those dreary misconceptions. Evidently, the French Quarter is – and has been for over 300 years – a pulsating commercial center where people of diverse origins have lived, worked and celebrated life.

The renovated, three-story townhouse built in 1816 at 520 Royal St., showcases 300 original artifacts, including texts, illustrations, maps, paintings, photographs, retail and household items, artfully interspersed with interactive technologies to allow French Quarter history to become immediately accessible through imaginative, augmented reality. (There’s also a new rotating exhibition space; stay tuned for a story about its inaugural exhibit, Art of the City, next week.)

“Connecting with an original artifact is a powerful experience…but these interactive experiences provide other ways for people to understand the objects they are looking at and see them in a whole new way,” explained John H. Lawrence, director of museum programs.

THNOC’s 10 historic buildings include the Merieult House, which houses the Louisiana History Galleries, as well as the (Gen. Lewis Kemper and Leila) Williams Residence at 533 Royal St.; Williams Research Center at 410 Chartres St., which catalogs 35,000 items; and the Boyd Cruise Gallery and Laura Simon Nelson Galleries for Louisiana art. All told, THNOC’s holdings comprise one million objects, documenting local history. Until now, however, there was no large-scale, permanent exhibit that helped people understand the French Quarter, Lawrence said.

Entering the historic building, visitors board an elevator to the third floor and immediately step back in time. As the elevator car rises, a virtual window recreates a scene on the main floor inside Pierre Brulator’s 1850 wine shop. Rising to the entresol, they view a modest apartment from 1880. The third floor view shows an elegant 1920s salon when William Ratcliffe Irby owned the building.

Aeolian organ built in 1926. (Photo courtesy of: The Historic New Orleans Collection)

In the entry to Irby’s home, a massive Aeolian (Opus 1583) organ, built in 1926 symbolized his prominent social status. Restored by the Holtkamp Organ Company, it is one of only five surviving residential, player organs. Popular in homes before radio or phonographs, the organs played operas, symphonies and popular music – even Ragtime – recorded on a roll like a player piano, that could be heard throughout the house.

Many still remember the look of the Brulatour courtyard in the 1960s when WDSU-TV studio occupied the rear building (depicted in an enormous collage by graphic designer Tana Coman). The familiar patio can be re-imagined during four time periods (1820, 1880, 1920 and 1960) by peering through three “chronovoiseurs,” time-travel virtual reality binoculars, merging live action with historic photographs. To produce the videos, staff members enacted servants feeding chickens, black artisans building furniture, gentry languidly promenading and Arts Club members painting canvases en plein air.

Virtual reality binoculars show the courtyard in 1920. (Photo courtesy of: The Historic New Orleans Collection)

“Chronology can get complicated,” because so many events occur at the same time, according to Lawrence. By rejecting a rigid, sequential order, a team of historians, curators and designers conceived of eight separate themes, including maps, transportation, commerce, population, architecture, arts, and communication and music, to explore the quarter over long periods of time through a textural approach. The collection defines the museum, Lawrence said.

The first gallery displays 10 maps, highlighting different geographical perspectives. The oldest map in the exhibition,”Amplissimae Regionis Mississipi,” dated 1718-1724 and penned by Johann Baptist Homann, shows the entire Mississippi River Valley. Later maps illustrate the Vieux Carre’s street grid laid out by the French engineer Adrien de Pauger. Un Plan de La Novelle Orleans shows the city only four blocks deep. There is also a pictorial view from the West Bank and an 1883 (post-Louisiana Purchase) D.H. Holmes Dry Goods map detailed in Spanish and English. A lot has changed, especially after two major fires, but much has not.

One of the earliest maps. (Photo courtesy of: The Historic New Orleans Collection)

If Bienville were here, he could still find his way around, Lawrence chuckled. Additional details about each topic can be found by consulting electronic kiosks. Video of an extended interview with Tulane architecture professor Richard Campanella explains Pauger’s plan and other aspects of urban development.

An “animated word cloud” trickles down one gallery wall, showering hundreds of words that characterize the quarter. Particular verbiage is activated by sensors that pick up what visitors are touching and viewing. History is dynamic, but the way people engage with it changes, Lawrence remarked.

The so-called “Murmural” (mur being the French word for wall) was designed by New Orleans new media artist Xiao Xiao and Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Media Lab designer Don Derek Haddad whose specialty is responsive environments. Xiao Xiao collaborated with fellow MIT alumni, Haddad, Alan Kwan and Bjorn Sparrman on three interactive projects for the historic site.

“These pieces provide visitors with instant immersion into scenes from the past,” said Xiao Xiao who called the visual experiences “cinematic.” “In addition to reading about events or looking at isolated objects, they are able to explore richly detailed worlds. All of these technologies also play off the physical space in unexpected ways and in doing so give people experiences that they can have nowhere else.”

Since the French Quarter owes its existence to the Mississippi, the next gallery covers the important topic of transportation. The invention of steamboats in 1812 permitted goods to be shipped upriver, not just floated down, sparking an unparalleled era of prosperity. Arriving in 1835, the St. Charles streetcar was segregated by race, denoted by a “for colored patrons only” sign on display.

The St. Charles Avenue streetcar was segregated. (Photo courtesy of: The Historic New Orleans Collection)

In 1956, the Federal-Aid Highway Act allotted funds for a six-lane riverfront expressway to run through the French Quarter. Local preservationists opposed and achieved National Historic Landmark with National Register Places status to halt the project. Lawrence called their fight “a defining moment” in the quarter’s long history. “Maybe one person in 100 will want to read through the expressway plan,” Lawrence said, but the booklet is available in the research library and on an electronic kiosk for anyone who does.

In the commerce gallery, standout merchandise include African slaves, bought and sold at public auction. A St. Louis Hotel’s auctioneer’s 1859 sales pitch is chillingly recorded and audible on headphones. An authentic 1838 advertisement by J.B. Blache lists slaves by name and skill, describing them as “acclimated” and “first-rate house servants.”

Louisiana’s many residents began with tribal groups before 1700, including Chitimacha, Choctaw, Natchez, Tunica and others. Immigration continued with the influx of Spanish and French colonists, Senegambian slaves, Canary Islanders, Acadians and Haitian refugees through Sicilian immigrants. Photographs of 130 individuals underscore the city’s longstanding diversity, including Asians, gay and lesbian residents. For every image, there are 100 more in the research library, Lawrence remarked.

Paul Morphy’s chessboard. (Photo courtesy of: The Historic New Orleans Collection)

The quarter has long been the center of a thriving arts scene, especially during the early 20th century when writers William Faulkner, Sherwood Anderson and Tennessee Williams, as well as painters, performers and those of bohemian spirit gathered in clubs and private residences to share inspiration. Displayed objects include the first book of poetry written by Free People of Color and an armoire designed and built by the owner of the townhouse Francois Seignouret (1783-1852) who was a leading furniture manufacturer. For 30 years, the building was headquarters for the Arts and Crafts Club, one of the most important creative gathering places.

The French Quarter became the backdrop for several Hollywood Films, King Creole starring Elvis Presley and Panic in the Streets with Richard Widmark and Zero Mostel Burlesque and clarinetist Pete Fountain arrived on Bourbon Street. It goes without saying that New Orleans’ history is inextricably entwined with music – first opera, classical, then jazz and R&B.

The piece to resistance of the exhibition is an immersive film showcasing the history of the French Quarter after nightfall, developed by New Orleans writers and producers Michelle Benoit and Glen Pitre of the production company Côte Blanche. Projected on four walls, the film fills the space with imagery and sound. Over the course of a 17.5-minute journey, viewers are transported from a mosquito-infested Mississippi River bank prior to Native American settlement, to a contemporary night amid the Krewe de Vieux parade. The production employed hundreds of actors, musicians and film technicians, and some scenes, such as a Choctaw encounter with Europeans or a visit to the famed French Opera House, were produced in cooperation with Louisiana State University’s Screen Arts program. Animator Charlie Lavoy added movement and life to paintings, photographs and more from THNOC’s holdings.

****

The Royal Street campuses, including The Shop at The Collection Hours: Tuesday–Saturday, 9:30 a.m.–4:30 p.m. and Sunday, 10:30 a.m.–4:30 p.m.

The Chartres Street campus, including the Williams Research Center Hours: Tuesday–Saturday, 9:30 a.m.–4:30 p.m.

NOLAbeings

Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings

Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

Data corner: Adobe Suite (create a PDF, social media graphic, presentation, edit a photo and video

Data corner is where you go to work with analytics and top tech skills. It takes on everything from PERL and SQL to Canva and Sprout Social.

Data corner: Adobe Suite (create a PDF, social media graphic, presentation, edit a photo and video

Data corner is where you go to work with analytics and top tech skills. It takes on everything from PERL and SQL to Canva and Sprout Social.

Thank you for rerunning this piece. More people should know about this wonderful gallery.