Editors Note: The following series “Beyond the Beignets: A deeper look at New Orleans” is a week-long series curated by Rena Repenning as part of the Digital Research Internship Program in partnership with ViaNolaVie. The DRI Program is a Newcomb Institute technology initiative for undergraduate students combining technology skillsets, feminist leadership, and the digital humanities.

Because I live in New Orleans as a Tulane student, I often feel like a visitor instead of a resident because Tulane’s social life is disconnected from the city’s year-round residents. When creating Beyond the Beignets, I compiled 10 articles that articulated an often overlooked part of city life. Treme’s Petit Jazz Museum is not your average tourist spot. For the past 22 years Al Jackson has owned the museum’s property, but the museum is only a few years old. Jackson has a love and passion for authentic New Orleans culture and has stayed true to these values with his museum. Read on to see why Jackson spent 22 years putting together this authentic experience in this piece originally published on July 19th, 2019.

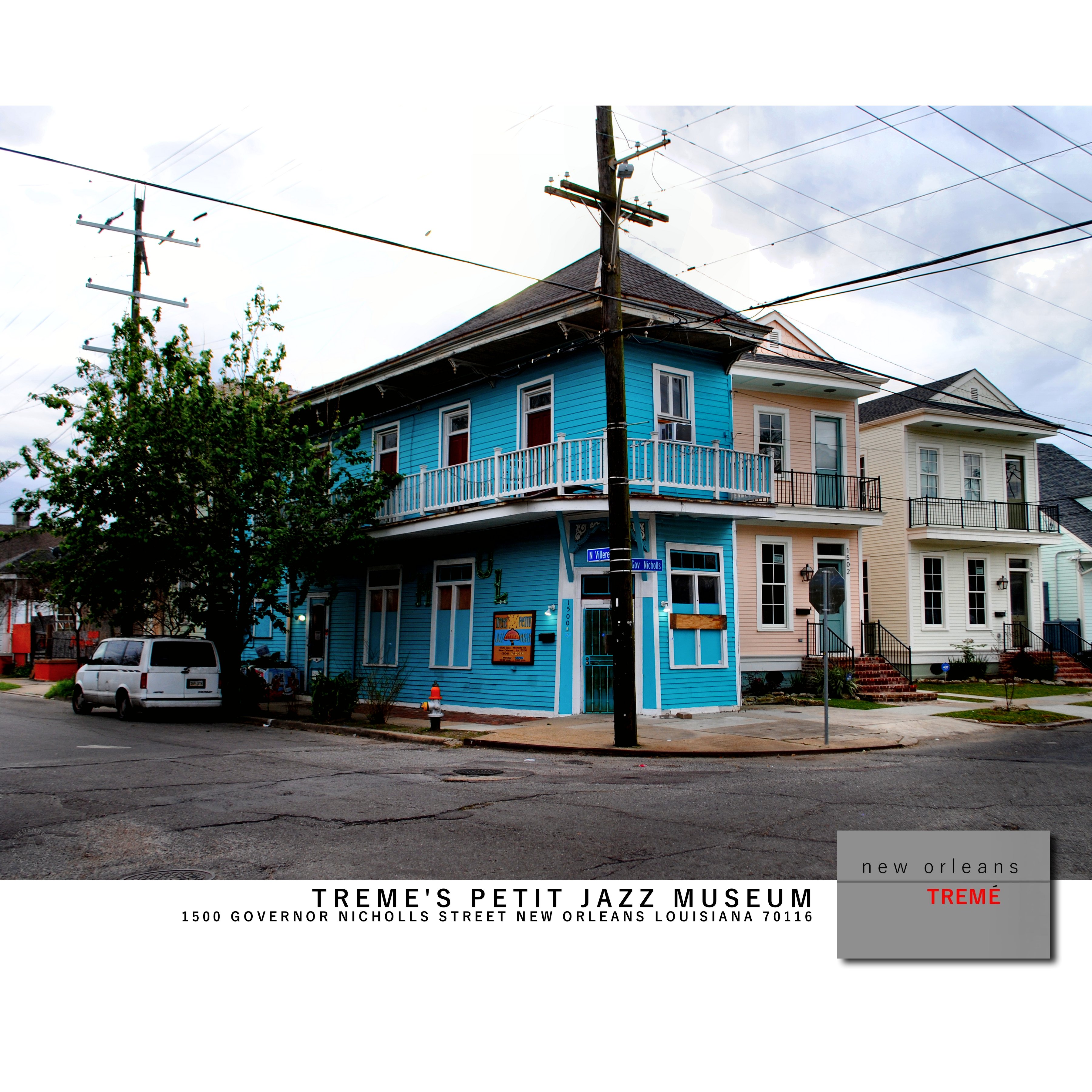

It’s easy, especially when we’re younger, to think of our current day’s culture as the most important and vital thing going on, to feel that it is uniquely singular and defining. What’s harder is placing it into context. That’s something Al Jackson has worked hard at as the curator and founder of Treme’s Petit Jazz Museum, which opened just a few years ago. This long-gestating project provides an excellent lesson about our city’s musical history and Al Jackson is happy share it with visitors both local and from far away. A few weeks ago, audio produce Sarah Holtz and I stopped by the museum to hear all about it from the man himself.

David Benedetto: I know, Mr. Jackson, that you’ve been a number of things in your life–

Al Jackson: Nice guy first! [Laughing]

DB: [Laughing] Nice guy first, but also six years in the Air Force, working for city government, data analysis on rockets–

AJ: Apollo 11

DB: — Apollo 11? Really?

AJ: Yeah! On the booster.

DB: And now you’re running a jazz museum as well. How did this dream for this space kind of start?

AJ: Well not in this particular space, but it started when I bought the home, which was once the Union Hall building on Claiborne and Columbus by Kermit Ruffins’ Mother-In-Law Lounge — that vacant lot. I bought it 18 years after segregation ended and the unions merged. We were going to clean it up, and I found these Louis Armstrong and Little Richard contracts [and I was] like, ‘Oh my God! What is this?’ So we decided then to really try to open a jazz museum. And it took us 22 years, but we’re here.

DB: You just took us on a lovely kind of musical tour of 200 years leading to the development of what we know as jazz. What went into you trying to bring that to a physical space? Because you have you laid it out really well. I know this must have been a challenge of research and trying to figure things out.

AJ: It really was, but it was a labor of love, which is good. I decided to buy some CD players and my brother gave me a little cassette player — to try to keep the music as authentic and real as possible. And that’s been a big help. And of course we love when someone [visits] and can play the piano- – [plays notes] — because she was built in 1898. And the harp is underneath. Take the harp away and there’s no sound from the piano. so we’re so connected [and] history is as important as music.

DB: What are the biggest misconceptions about the history of jazz that you’ve come across?

AJ: That it fell out of the sky. [Laughing]. Actually, the sad commentary is that most folks fail to give a critical thought to, ‘How the hell did this happen? What did it come from?’ Africans don’t play brass instruments, but John Coltrane and Miles Davis were some bad boys, as well as Louis Armstrong. What did it come from? No one connects the dots that the brass side came from the military during the Civil War when freed slaves were taught by Prussians or Germans — who were mercenaries — to play brass and reed instruments; that’s true. That’s real.

DB: One of the things you’ve brought up before is that we talk about the Jazz Fest beginning in the 1970s, but there was one before that, right?

AJ: There were 20 jazz fests before the 1970s. The first was 1949 with George Lewis on clarinet at Congo Square. Louis Armstrong in 1968, his only Jazz Fest; 1955, Papa Celestin’s Band again in Congo Square; and in 1959, Chris Barber came from London to Jazz Fest. So why the folk today are ignoring those folk from back then? It begs the question. George Wein [founder of Newport Jazz Fest] could not have come to New Orleans until 1970, which is when segregation really ended. His wife was black, so he could not come without going to jail for sleeping overnight with his wife. So he could not come until 1970, which is when he produced the first Jazz and Heritage Festival, and it has been known as the Jazz and Heritage Festival ever since. Though it’s always spoken of as Jazz Fest, [which denies] the existence the [original] Jazz Fest when there are posters and other information out there.

DB: I know you grew up in Treme.

AJ: Yes, in the Lafitte condominiums across the street from Dooky Chase.

DB: So you have been watching this neighborhood evolve for a long period of time and you now own a space that is really representative of this wide swath of history of it. How do you feel about that?

AJ: I feel good about it. My only disappointment is when I encounter someone who does not really appreciate the culture and so I’ll ask to buy their home so they can go back where they came from. It’s easy. Don’t fuss, sell your house and leave! [Laughing]. It’s easy.

DB: This is kind of a simple question — what do you personally love about jazz? What keeps you listening to the music and appreciating the music?

AJ: It is not as much about the music as it is about the history of people who understood that we can always come together, have a pint of beer, play some great music, create other great music and life goes on. It’s about the history of the connectivity of people and instruments that we all should know. And I think it would give us a better appreciation for each other. We all can play music, but if you don’t understand where it came from and what it took to get there you’re missing the boat.

It’s sharing information. I don’t want to die and take it with me. You remember King Tut? His gold is still here, 2500 years later. Still, you can’t take it with you, so share it.

DB: Do you have any hopes for the museum growing into something else? Is there anything that you would want to add to the collection?

AJ: Yes, there’s an entire segment which I have not included yet [which is] the local 496, which was the Negro Musician’s Union, and I would hope that the State Museum would find a way to partner with us and incorporate what we’re doing with what they’re doing. Collectively it would become phenomenal and with the state involved, it would outlast me. All of us. That’s what I’m hoping for.

***

Treme’s Petit Jazz Museum is located at 1500 Governor Nicholls St. in the Treme Neighborhood. You can find out more information about it at www.tremespetitjazzmuseum.com.

***

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

NOLAbeings

Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings

Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

Data corner: Adobe Suite (create a PDF, social media graphic, presentation, edit a photo and video

Data corner is where you go to work with analytics and top tech skills. It takes on everything from PERL and SQL to Canva and Sprout Social.

Data corner: Adobe Suite (create a PDF, social media graphic, presentation, edit a photo and video

Data corner is where you go to work with analytics and top tech skills. It takes on everything from PERL and SQL to Canva and Sprout Social.