(Photo: Courtesy Nola DNA / Intelligent Archives)

Last month I sat down with writer, print maker, and founder of New Orleans DNA Joseph Makkos to talk about his local preservation project, it’s evolution, and what he hopes the future holds.

***

David Benedetto: A little background for our readers here — you randomly stumbled across a Craigslist ad about a historic collection of local newspapers from over 100 years ago spread into 30,000 airtight tubes that was being given up. When you arrived there, in that moment, what were you thinking?

Joseph Makkos: I don’t think it was so random because the truth of the matter is my first job ever was as a paperboy. And I also have worked in paper and books and grew up in antique shops. So I think I was prepared to respond to that ad and to get on my bike and get there as fast as I could so that I could stand and behold whatever it was that I was about to see.

And when I walked in the door of this storefront behind the Dixie Brewery, I saw this archive in these tubes, in these boxes filling up the space. And at first I couldn’t really believe [it], but as I started to see really what it was, I realized in that moment that this was something that had to be saved.

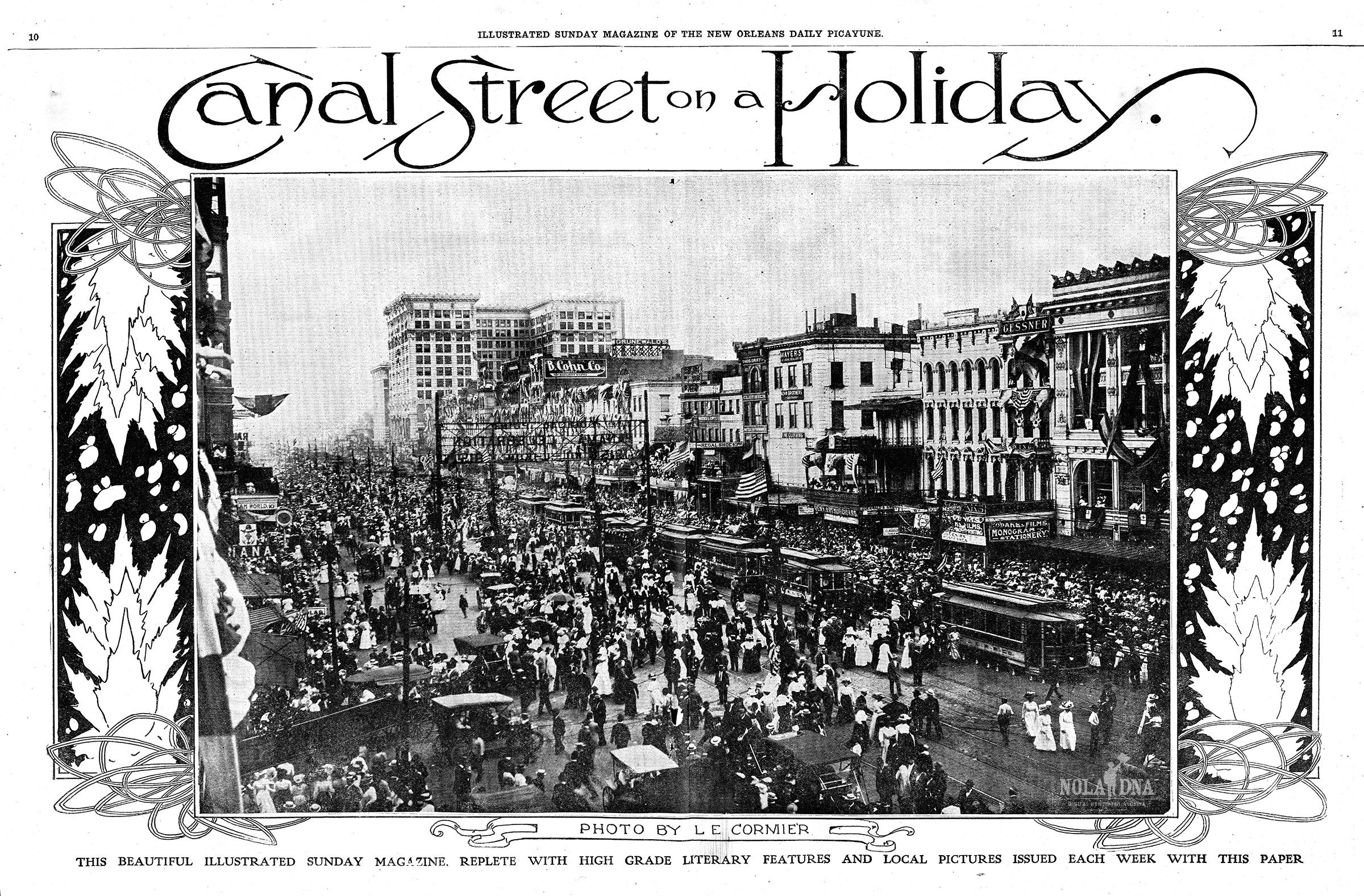

DB: I think that’s really beautiful. And so you now have this collection of historic documents from I think 1885 to 1929?

It’s actually a little bit more expansive. There’s a Harper’s Weekly collection that goes back to 1857, and I would say a good three-fourths of that collection is actually Louisiana and New Orleans-related Harper’s content. So it’s a real interesting collection that focused on Louisiana and the South from this Antebellum—1857 through Reconstruction— time period. And that really ends around 1899 when Harper’s changed into more of a magazine [and] less of a newspaper.

And then the Picayune Archive— which is the Daily-Picayune at first and then that sort of comes into the Times-Democrat. And [then] there’s a merger, and we have some really cool Times-Democrat/Daily Picayune double masthead papers kind of like what people in New Orleans would remember the States Item/Times-Picayune double masthead, or, as we have it now, the New Orleans Advocate and The Times-Picayune double masthead.

(Photo: Courtesy Nola DNA / Intelligent Archives)

So there’s actually precedence for having these merger periods where there’s both brands sort of coming together under a single paper. And so we get to see this really particular time period in New Orleans history and this Louisiana scope done by this Northern paper ,and then leading into the Picayune and the age of Eliza Jane Nicholson— this woman entrepreneurial, literary poet—who married the Colonel who owned the newspaper and, when he passed away, got the paper and in this strange way she became the de-facto first female publisher of a major American newspaper here in New Orleans.

So the beginning of our archive begins right there sort Eliza Jane’s last decade. And then as her sons take it over in the 1890s and then into the 1900s where it gets picked up and merges with the Times-Democrat. And it’s really a dizzying history, but it’s a really important time period. If you start to dig into what’s been written about this era, and specifically in relation to the newspaper, it’s not much so [this archive] really leads us onto a lot of areas for exploration and re-exploration.

DB: How did this evolve into your New Orleans DNA project?

JM: I’ve talked about this in other pieces that have covered the story, and sometimes we stay too much in the origins, and I’m really ready to move beyond the origin story of how this thing came to be. But it’s important I suppose to note because in talking about the fascinating story of how this archive survived a Nazi bombing in England and how it was owned by the British Museum and how they got rid of it and how it made its way back to New Orleans — the fact that it’s in Louisiana and there’s new resources that are opening up and I’m taking a really particular look at ways that we can really bring this into the digital humanities, looking at literature and looking at really getting into the way it relates to writing, but also the way it relates to research and archives and tying it into — [making art] into a capital ‘A’ to make ‘STEM’– Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math– into STEAM. [Because] the arts and humanities really can empower the rest of all that in a way that really nothing else can.

(Photo: Courtesy Nola DNA / Intelligent Archives)

We can pull all these ideas into STEM through the A. And the A becomes like an access point for so much content. Because you can know technology and you can be the best web designer, but unless you have really good driving content that moves us more into understanding of ourselves through technology, through the human condition, through cutting it up in a way that’s maybe attuned to our interests and our senses in new ways — unless we can do that with really good content than the programming is all for nothing. You can have the most sophisticated algorithm, but unless you’re powering it with clean data that can really show us something specific in particular that’s really exacting then, what are we doing it for? I love all this technology and embrace it, and I can firmly say that I am a futurist in thinking about ways that this can work in ways that it can become accessible in all different directions, and that’s what gets exciting is to be able to build with a new set of tools.

I think we’re in a time period where society is actually announcing to us that we’re ready for a shift. We’re in a shift. I don’t know from the beginning or the middle of the end, but I think we’re kind of in a shift that leads up to a bigger shift. And I actually push first for technology literacy because I think the more that we can really understand what these things are as the technology curve rises I think we just need to become more literate about the way that these things that we see and perceived as advanced can be boiled down and then used in ways that are very functional for us. And I think that’s where technology literacy can help us and reinforce our ability to curate and our ability to use it for better pathways.

DB: And I guess you see Nola DNA as a kind of a focalizing force in this?

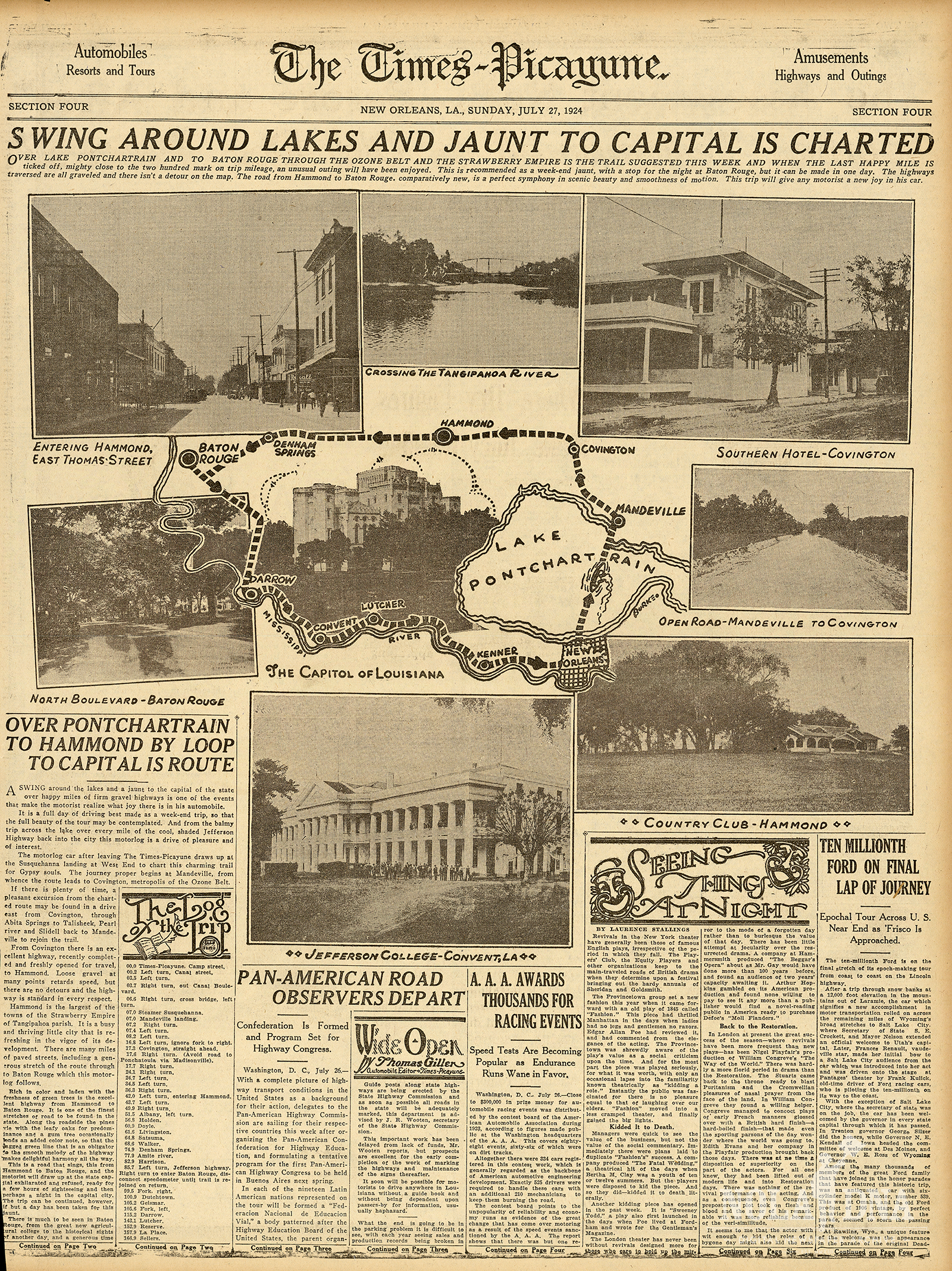

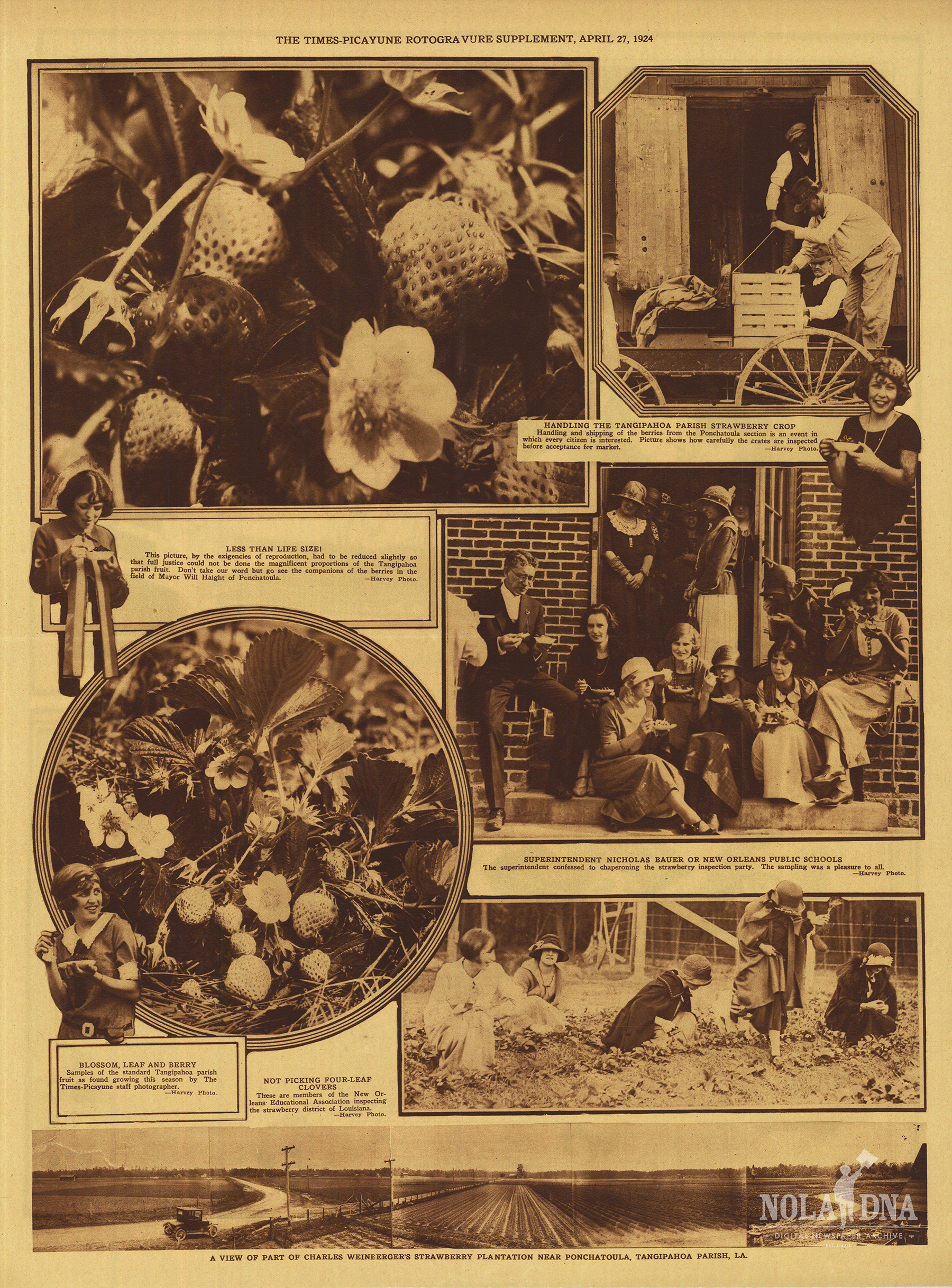

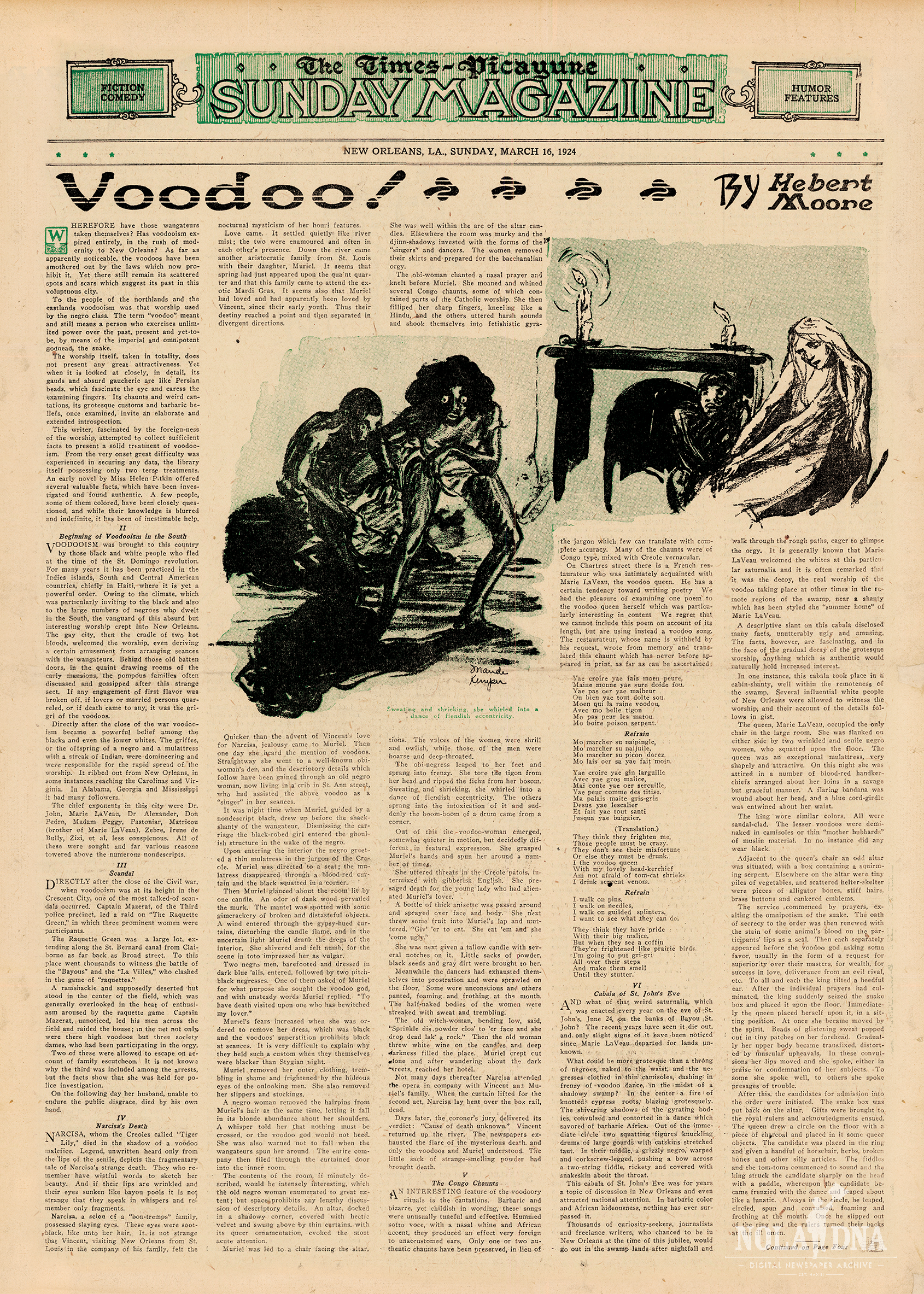

JM: I got off track there. [Laughing]. But, yeah. I want people to like close their eyes and consider what is possible with 700,000 sides of newsprint. It’s a lot of content, and I want people to consider what it is really instead of just thinking of it as a newspaper archive. One thing that people think is it’s just this black and white thing on this rag paper, and it’s ephemeral. And, yes, it’s ephemeral, but these copies are in impeccable condition, and it’s not just newsprint, but color [and] there’s all sorts of dynamic photographs, puzzle sections, all sorts of really amazing stuff. And if we re-contextualize it and we re-curate it — it’s not really newspapers anymore; it’s an encyclopedia of knowledge about New Orleans.

(Photo: Courtesy Nola DNA / Intelligent Archives)

And once we take all that and bring it in and then allow it to be accessed to a bunch of different programming languages, there’s all sorts of really dynamic ways that we can visualize the data. That’s what gets exciting is thinking of the large scale, like over the course of decades, and being able to look at a data-set and then also be able to take one week or one three-day flashpoint in New Orleans history and add a data-set and geo-tag it and then bring in the different voices of people that are interviewed in the paper and look at who they are and then grab biographical data for them. And what about if we take another news source in the city and then grab their information about that flash point and then that becomes another layer? If we start to really consider all the different things in that intersection then [people can] start to have this different view of their environment. I think could become really illuminating. It could become incredibly dynamic.

DB: That’s a really interesting way of making the macro and micro of tangible history approachable. In the short term right now, moving forward in 2019 to 2020, what are your hopes for this short period of time going forward?

I think what we’re doing now is working on the scan plan and thinking about process — how do we go from a stack of newspapers over here and bring that in and digitize it and then do the optical character recognition and start to do metadata. Like, how do we go from ink and newsprint to quantum? There’s a certain point where we have the data where all of a sudden you can take a bunch of different pathways [so now] we’re making our scan plan and we’re gonna experiment with photography and do a little bit more fine tuning on. We’re also gonna be launching a [merchandise] site soon, so we’re gonna have some really interesting products that we’re gonna be making from the archive and we have a print shop so we try to really respect the content and make these really beautiful products that people can enjoy and have a piece of it something really authentic also.

And then we’re going to start ramping up our scanning process and one of the first projects we’re gonna do in 2020 is we’re gonna do this whole collection, and we’re gonna come out with and show people what we can do. It’s gonna be these Sunday magazines from 1905 through 1914, and it’s really captivating stuff because they have color covers. They have really crazy awesome ads on the back, color ads for Cornflakes, 1899 Coca-Cola — it’s like the beginning of color advertisement in a certain sense. And then inside of these there’s photo sections [where] these amazing photographers [went] out and they just shot these amazing Louisiana landscape shots ,and they go into cities, and they photograph 12 photographs in Morgan City or all these different cities around the state, and they’re going and capturing this really specific time period. And also there’s syndicated fiction and syndicated non-fiction essays. And then there’s also a lot genealogical stuff because people would send in photographs of their children, so there are these pages where there’s like 12 photos of kids from like 1905 — that’s people’s great grandparents.

It’s a little bit of everything. It’s going to enable us to bring online a really particular set of stuff that’s gonna be, I think, really impactful for looking at what things were like 100 years ago, and it has a lot of reach that I think can be utilized and amplified in many different medias.

***

More information about NOLA DNA and Intelligent Archives can be found at www.intelligentarchives.org and through www.noladna.com.

This interview was condensed and edited for clarity.

NOLAbeings

Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings

Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

Data corner: Adobe Suite (create a PDF, social media graphic, presentation, edit a photo and video

Data corner is where you go to work with analytics and top tech skills. It takes on everything from PERL and SQL to Canva and Sprout Social.

Data corner: Adobe Suite (create a PDF, social media graphic, presentation, edit a photo and video

Data corner is where you go to work with analytics and top tech skills. It takes on everything from PERL and SQL to Canva and Sprout Social.