Underneath the interstate overpass, gleams the smile of Travis “Trumpet Black” Hill, who’s music remains as permanent as his colorful portrait on the cement wall of the Oak Tree Apartment Complex in New Orleans’ historical Tremé neighborhood. Located on N. Claiborne Ave. and Gov. Nicholls St., the two-story mural of Travis “Trumpet Black” Hill was painted to commemorate the late brass musician, who passed suddenly at only 28 years old in Tokyo, Japan following the spread of an infection on May 4th, 2015.

Nicknamed Travis “Trumpet Black” Hill by fellow musician, James Andrews, Hill grew up in New Orleans surrounded by some of the city’s most talented musicians– from his grandfather, Jessie “Ooh Poo Pah Doo” Hill, to his cousin, “Trombone Shorty”– in the 6th Ward (10). After having spent time in juvenile detention centers growing up and having served just over eight years for armed-robbery, Travis Hill focused the latter half of his life on bettering himself and sharing his talent across the globe (10). Following his release from jail in 2011, Hill said, “I was a young kid when I went in and I came out as a man” (10).

The use of vibrant blues and purples, contrasting against the orange and yellow backdrop illustrates to the spectator that this man left a powerful, positive, and bright imprint on the lives and culture of New Orleans and on New Orleanians. The yellow and orange invokes a sense of warmth, appearing as though the sun is setting or rising behind Hill’s body. The blues and purples of his skin, clothing, and trumpet invoke the sensation that he frozen in time on the wall. Hill is painted peering up into the sky grinning, as though he is peering up towards heaven. His sunglasses, white teeth, and trumpet glisten white against his skin. Inscribed at the bottom left-hand corner is “Travis Hill ‘Trumpet Black’” with a small halo around the “T” of “Travis,” indicating that the mural is one of memorial.

The portrait was painted by local muralist and video producer, Brandan Odums, who had met Hill at a music video shoot for Hill’s cousin, Trombone Shorty’s, “Fire and Brimstone” video (3). The pair had intentions of future collaborations, which unfortunately would never come true.

Photography Credit: Gus Bennet

“I knew I wanted to do this mural,” said Odums after hearing the news of his friend’s passing (3).

The inspiration for the portrait was a photo taken by local New Orleans photographer, Gus Bennett. Using the vibrant warm and cool tones, Odums painted Bennett’s photograph of Hill on the apartment complex’s outward facing wall, beaming over a patch of green grass and picnic tables. Despite having had permission to paint the mural in various locations around the city, Odums decided on using the wall off of N. Claiborne because of the Tremé neighborhood’s deep rooted history within the African-American, Creole, and musical communities (5).

The Tremé neighborhood of New Orleans was named after Claude Tremé, a hat maker and real estate developer who migrated from France to New Orleans in 1783, despite only having owned a small portion of the neighborhood for just about a decade (9). Known as being the oldest African-American neighborhood in existence, Tremé was inhabited by free persons of color, whom had earned, bought, or bargained their freedom and who could finally own their own property (9). In 1724, the French, who occupied Louisiana, implemented “Code Noir,” which made Sunday a “day of rest” for enslaved peoples (2). Tremé is home to Congo Square, an area where both free and enslaved Africans would gather to sing and dance, and is commonly referenced as the birthplace of Jazz music (2). Between 1763 and 1802, the Spanish occupied Louisiana and relaxed “Code Noir” to allow the enslaved to sell food and handmade items in the square, allowing the enslaved to purchase their freedom (2). Unlike the rest of the United States, where enslaved Africans were stripped of their cultures, traditions, and even dignities, African food, language, and celebrations were conserved in the Tremé neighborhood. Today, the Tremé neighborhood (and New Orleans as a whole) remains a hotbed for jazz music, Creole cuisine, and African culture– all stemming from it’s deep-rooted history. The neighborhood is additionally home to Louis Armstrong park, commemorating the music legend, of which many second-line and jazz funerals frequent.

To those unfamiliar with the neighborhood’s history, the placement of Odums’ mural might seem strange. Underneath the garbage-ridden overpass, bestrewn with black clouds of passing car’s exhaust fumes, with very little foot traffic– it does not seem to be the ideal location for a beautiful memorial. However, the placement of Travis Hill’s mural in the Tremé neighborhood is a sign of respect and honor to the impact and legacy he made within the African-American and musical communities, and places him alongside legends like Louis Armstrong.

Having studied art and film in college, Odums began experimenting with painting and murals in blight buildings in the 9th Ward of New Orleans, deserted post-Katrina (7). Many of his murals commemorate significant people, events, and places in American history, for example Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Frederick Douglas, as well as many other prominent Black civil rights leaders (7).

“Basically I painted people I really admired throughout history,” he explained. “Since high school I’ve always found an excuse or a reason to draw or paint people I’ve always looked up to. For me it’s a way of connecting with them,” said Odums (7). With this said, Odums is placing Travis Hill on a pedestal in the same way he would place some of the most impactful individuals the world has ever seen, ensuring that he is a man worth remembering.

“Painting those portraits was up-lifting. Portraits in general were often reserved for the rich and royalty, so doing a portrait of a person lends to the idea of that person being valuable,” Odums continued (7).

The value of public art is that no two viewers have the same experience or engagement with the piece, or what they think it is supposedly depicting. To those familiar with the life or work of Travis “Trumpet Black” Hill, his portrait may evoke feelings of remembrance, joy, or perhaps even sadness. In my own reflection with the piece, I found myself curious. Having had no prior knowledge on the background of Travis Hill or of the mural itself, I approached the wall questioning: What did this man do to have earned this level of commemoration? What did his (presumed) impact look like?

Methods of communication rooted in creativity, like art and journalism are meant to make the viewer question the piece’s purpose and meaning. Both mediums intend to convey a message or meaning to the public. Art and journalism both strive to “demonstrate how the new philosophy,” or a new perspective, “could be made relevant to people’s daily lives” (1). Good journalism, like good art, is thought-provoking, confusing, emotional, and reflective. Like music or journalism, art “requires a commitment to experimentation– to the belief that public art and public life are not fixed” (6).

In her journal “Temporality and Public Art,” author Patricia C. Phillips discusses this further by stating:

“Clearly, public art is not public just because it is out of doors, or in some identifiable civic space, or because it is something that almost everyone can apprehend. It is public because of the kinds of questions it chooses to ask or address, and not because of its accessibility or volume of viewers” (6).

The purpose of creating a mural in remembrance of Travis “Trumpet Black” Hill was not to elicit feelings of sadness or of anguish. Rather, Odums’ decision to paint a portrait of Hill was one of celebration and resilience, celebrating his life, recovery from his troubled past, and his ongoing legacy in the music community.

“In New Orleans,” he said, “we celebrate life. We mourn, but beyond the mourning, we have a celebration” (5).

Second-line jazz funeral gathers at Travis Hill’s mural in Tremé. Credit:http://bmike.com/project/commissioned-murals/

Stemming from West African ritual, the concept of festivity at times of loss and mourning is something relatively unique to New Orleans (8). Jazz Funerals take place in New Orleans after the passing of significant community figures, and are common among African-American men (8). Following an individual’s funeral service, funeral attendees and even stragglers from the street, march from the service to the cemetery to upbeat, joyous brass music to celebrate the individual in a positive rather than a negative light (8). Like Odums’ mural, written obituaries are supposed to censor anything controversial that may represent the individual in a negative light.

Rather than touch on Travis “Trumpet Black” Hill’s mistakes in his youth, his mural, parade, and legacy censors the negativity and instead is focused on his successes, and his musical impact. The mural commemorates growth, resilience, and change that resonate not only in the life of Travis Hill, but of the city of New Orleans, and the Tremé neighborhood. Like these second line parades and jazz funerals, Odums’ mural uses the death of Travis “Trumpet Black” Hill as a space and time to reflect on joy and life in the moment of death.

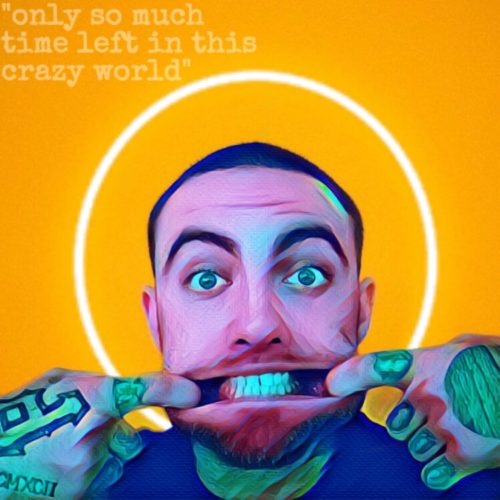

Using Odums’ mural of Travis “Trumpet Black” Hill as inspiration, I created my own mural of Malcolm “Mac” Miller. Mac Miller was a famous rapper who passed September 7th, 2018 of an accidental drug overdose. While Mac had his demons, he brought joy into the lives of millions (including mine) and is continually commemorated for his ongoing legacy. “Only so much time in this crazy world,” as quoted in the image, was one of Mac’s many tattoos.

References:

NOLAbeings

Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings

Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

Data corner: Adobe Suite (create a PDF, social media graphic, presentation, edit a photo and video

Data corner is where you go to work with analytics and top tech skills. It takes on everything from PERL and SQL to Canva and Sprout Social.

Data corner: Adobe Suite (create a PDF, social media graphic, presentation, edit a photo and video

Data corner is where you go to work with analytics and top tech skills. It takes on everything from PERL and SQL to Canva and Sprout Social.