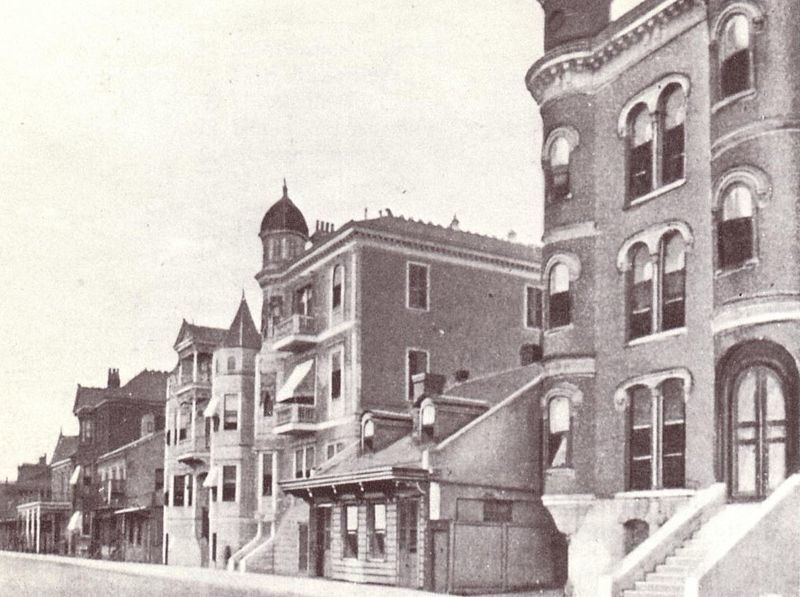

New Orleans: “Basin Street Up the Line”. View is of the high-rent section of the “Storyville” Red light district. Block of visible buildings includes from left to right Tom Anderson’s Saloon (with pillared sidewalk gallery), the brothels of Hilma Burt, Diana & Norma, Lisette Smith, Minnie White, Josie Arlington (with rounded cupola), Martha Clarke (smaller older building) and Lulu White’s Mahogany Hall is closest building at right (photo by: from common collective of 1907)

Editor’s Note: The following series “Boots n’ Blues” is a week-long series curated by Kila Moore as part of the Digital Research Internship Program in partnership with ViaNolaVie. The DRI Program is a Newcomb Insitute technology initiative for undergraduate students combining technology skill sets, feminist leadership, and the digital humanities.

In the toe of Louisiana lies one of the world’s greatest contributions to music: the city of New Orleans. The trumpets and saxophones heard from the city’s infamous second-lines have inspired so much of the music we hear today — from jazz (New Orleans’ specialty), to blues, bounce, and hip-hop — its legacy on the sound of America’s music is unprecedented. This collection of articles explores the presence and impact of New Orleans’ music scene from the red lights of Storyville to the neon lights of Bourbon Street. And while the streets are silent from the effects of COVID-19, it is the perfect time to remember why music is so important to so many. New Orleans’ historic Storyville is most known for once being a redlight district, but the area was also the heart of much of the city’s music scene. Read this article, originally published on August 17, 2017, to learn more.

Storyville might be best known for its legalized prostitution, but the red-light district that shut down a century ago also had more music being played on any given night than any other part of the city.

Many of the Madams who operated the brothels in the district were trying “to create or curate an atmosphere of entertainment and frivolity and fun,” says Eric Seiferth, a curator of Storyville: Madams and Music, an exhibit currently on display at the Historic New Orleans Collection. “So if you didn’t have the right music, it wasn’t going to work.”

Different types of music could be found in different parts of the district, Seiferth says. Along Basin street, home to the most elaborate brothels, “typically there you would have piano players referred to as ‘professors’ playing either by themselves or sometimes there might be a small string ensemble.”

The piano players were called ‘professors’ because they were the highest level of popular musician of the time and place, Seiferth says. “These guys, men and women, were typically able to read music and they were typically very well versed in all of the popular music of the period.”

And you had to be. “This is a time before radio,” says Seifterth. “It’s right at the beginnings of recorded sound, so there’s not a lot of options to hear your favorite song other than to have someone play it on the piano.

“People were spending a lot of money in these places,” he adds, “so you wanted the music to be on demand, and you wanted it to be good. And if you couldn’t do that you probably wouldn’t last very long.”

But some of the best, most innovative music in the district could be found outside the brothels and cabarets, says Seiferth. “There are honkytonks, there are dance clubs, there are saloons…there are lots of places to hear music and go dancing and have a drink in this area, and the music that was being played in these places was not necessarily the same music being played in the brothels.”

In these establishments, you might find six or seven-piece groups like the Imperial Orchestra or the Tuxedo Dance Band, with a front line cornet, (just like a trumpet), clarinet, and trombone, with a rhythm section of three or so people behind it, according to Seifterth. “These are your dance bands, and they’re going to be playing a lot of ragtime, a lot of songs just popular in era…and sometimes popular tunes taken from more classical pieces as well. But I just want to be clear about that diversity of musical types and things you could go listen to while you’re there.”

The abundance of venues and opportunities to play also created some healthy competition, further advancing the music, says Seiferth. There are numerous records and oral histories of musicians playing at bars across the street from one another, “and they go back and forth and there’s probably a lot of exaggeration going on in these stories but the point comes across that there was opportunity to push each other and to experiment.”

One such establishment, the Frenchman, often featured Tony Jackson and Jelly Roll Morton, going back and forth, often all night long, “to see who was the best, who had the freshest idea, the most innovation on the piano, and the best skills,” says Seiferth.

This kind of one-upsmanship, while critical to the development of jazz, does not mean that Storyville was the birthplace of the form, Seiferth says. There is music being played all over the city – it’s just that so much of it was concentrated in Storyville.

And at that point, “jazz is a style of playing music more than anything else,” he says. “Jelly Roll Morton talks about this. He says ‘you can play anything in jazz time if you know what you’re doing.’”

It’s the ability to add syncopation, improvisation, blue notes, Seiferth says, “oftentimes heterophony when you’re in the bands, where you have multiple voices playing the same melody together, just weaving it together, once you have groups that are doing this, you have them playing songs with jazz styles.

“So you could play just about anything,” he adds, “as long as you’re including those techniques, and that’s kind of the beginnings of jazz.”

Storyville, Madams and Music, runs through December 9th at the Historic New Orleans Collection’s Williams Research Center (410 Chartes St.).

NOLAbeings

Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings

Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

Data corner: Adobe Suite (create a PDF, social media graphic, presentation, edit a photo and video

Data corner is where you go to work with analytics and top tech skills. It takes on everything from PERL and SQL to Canva and Sprout Social.

Data corner: Adobe Suite (create a PDF, social media graphic, presentation, edit a photo and video

Data corner is where you go to work with analytics and top tech skills. It takes on everything from PERL and SQL to Canva and Sprout Social.