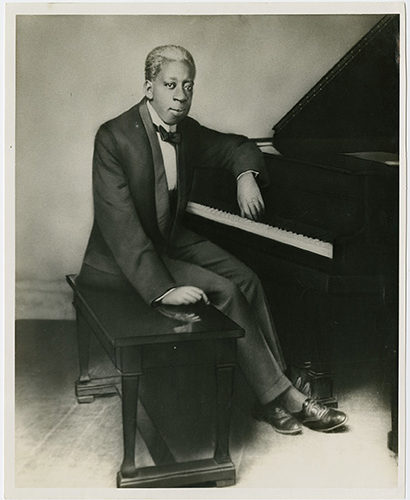

Tony Jackson; gelatin silver print; The William Russell Jazz Collection at The Historic New Orleans Collection, acquisition made possible by the Clarisse Claiborne Grima Fund, 92-48-L.241

There’s a segment in the 1947 movie New Orleans, starring Louis Armstrong and Billie Holliday, that depicts Storyville–the city’s notorious red light district–on its final night before closing a century ago.

“You have all the madams and the women congregating with the musicians….and bemoaning the demise of the district and packing up their little suitcases and parading out of Storyville,” says Pamela Arceneaux, author of Guidebooks to Sin: The Blue Books of Storyville, New Orleans.

And like most film depictions of New Orleans, “it’s inaccurate,” says Arceneaux.

In reality, by the time Storyville closed on November 12, 1917, “…a good number of the madams had moved on to greener pastures elsewhere, and a number of the brothels were already closing down. The red hot Storyville wasn’t quite as red hot by the time the closing bell sounded,” she adds.

A more accurate look at the district can be found at the Historic New Orleans’ Williams Research Center through the exhibit “Storyville: Madams and Music.”

“The idea was that we wanted to commemorate the centennial of the closing of the district,” says Arceneaux. Visitors will be able to see documents that established the district in 1898, maps showing prominent locations where the musicians worked and gathered after work, and of course, the famous “blue books.”

These directories would list the district’s working women by name, race and address, says Arceneaux. “The madam is almost always complemented as a queen among queens, her ladies are celebrated entertainers, all fine ladies welcoming gentlemen who are in need of release and entertainment during their visit, that sort of thing.”

The house itself is also always complemented. “The best oil paintings from Europe, cut glasses, artifacts from exhibitions are on display,” Arceneaux says. “It’s almost like visiting an art museum, and oh by the way there’s commercial sex available.”

But the blue books were more marketing than reality. As Arceneaux says, “Storyville was all about selling the sizzle, not the steak. The blue books promoted glamour, promoted the exotic, the taboo. The reality is that there were a handful of these top of the line houses, but the majority of the houses were working class, the kind of brothel that you’d find just about anywhere.”

At the lowest end of the scale were the “cribs,” which were rented. “People didn’t actually live there,” says Arceneaux. “They supported shift work by prostitutes and they were pretty much 24 hours, 7 days a week.”

Race factored in a number of ways. “There were several houses that advertised in the blue books or through word of mouth on the street as octaroon houses,” says Arceneaux. “These houses featured light skinned women of color and it played into an antebellum fantasy harkening back to the so-called quadroon balls, where white men of means would be able to secure the attentions of a woman of color, and Storyville actually marketed this kind of a nostalgic look back at an old south that certainly wasn’t to be admired.”

Entrepreneurs like Lulu White made the most of marketing women of color and marketing this fantasy, Arceneaux says. “Lulu was quite skilled in self-promotion. She issued her own guidebook to Mahogany Hall [her brothel]. She was also known as the diamond queen, as she wore her entire collection of fabulous diamonds all at once, descending the staircase to the sounds of ‘When the Pale Moon Shines’, her signature song.”

But White would ultimately lose all of her property, and she died ill and broke. And Storyville itself was fading fast toward the end. Over its twenty years of existence, “attitudes changed,” said Arceneaux. “A new generation had arisen, and instead of trying to keep prostitution into one area, they wanted to wipe it out forever and for all. “

Also in 1917, the United States entered World War I, “and recruiting offices were discovering that a great number of recruits were already infected with venereal diseases,” Arceneaux says, “so the idea that prostitutes carried disease affected legislation that demanded that the district be closed and broken down.

“It didn’t really stop prostitution of course, it just scattered it all over town,” she adds. “The situation reverted to what it had been before the Story ordinance had been enacted.”

Storyville: Madams and Music has been extended to run through December 9th. For more information, visit http://www.hnoc.org/exhibitions/storyville-madams-and-music.

NOLAbeings

Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings

Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

Data corner: Adobe Suite (create a PDF, social media graphic, presentation, edit a photo and video

Data corner is where you go to work with analytics and top tech skills. It takes on everything from PERL and SQL to Canva and Sprout Social.

Data corner: Adobe Suite (create a PDF, social media graphic, presentation, edit a photo and video

Data corner is where you go to work with analytics and top tech skills. It takes on everything from PERL and SQL to Canva and Sprout Social.