Editor’s Note: We at ViaNolaVie know the importance of words and how powerful those words can be when they are spread. We strive to produce a space where equality and fairness can shine. We are reposting Joseph Chanoff’s piece “New Orleans: Recovery Success Story or Case Study in Gentrification?” in honor of his work, his voice, and his ideas that push back and challenge. It originally was published in November 2019.

Gentrification is often viewed as an evil force that must be stopped. Noted gay-rights author Sarah Schulman once decried gentrification as “a process that hides the apparatus of domination from the dominant themselves, […] the removal of the dynamic mix that defines urbanity” [14]. While gentrification is a serious issue that perpetuates oppression and disfigures neighborhoods, the problem has deeper nuance, as must any potential solution. This is particularly evident in New Orleans, where Hurricane Katrina catalyzed gentrification’s timeline from decades to one that occurs virtually overnight. The underfunded Housing Authority of New Orleans (HANO) has had little success in combating gentrification. A holistic approach to curbing gentrification in NOLA must include an immediate expansion of the city’s Section 8 Program and more careful zoning regulations moving forward.

Gentrification has always been a personal issue for me given my family’s relationship with real estate. My father immigrated from Jamaica to Bedford Stuyvesant, Brooklyn in the late 80’s. At the time, BedStuy was considered dangerous, and the real estate prices reflected that. With savings earned driving a taxi, my father purchased a multi-family building for less than one tenth of its current value, which he rented and would later sell. As a function of circumstance, his early tenants were often white folks seeking the cheap rent or alternative lifestyle that Brooklyn had to offer.

For most of my life, I’d never considered this process to be gentrification. To me, it was always the story of my father’s climb from immigrant cab driver to landlord. As I grew older, I watched the great financial crisis shine a light on the harsh economic realities of real estate. At the time, the news was plastered with headlines that foreclosure rates had spiked more than 80% and that millions were losing their homes [6]. With the ugly side of real estate at the forefront of the public zeitgeist, I began to wonder if what my father had been doing for decades was contributing to gentrification.

Certainly, gentrification is bad. As Bruce Mitchell, Research Analyst with the National Community Reinvestment Commission, comments “[Gentrification] qualifies as an emergency in the sense that we have a housing affordability issue, or you have large numbers of renters who might be pushed out of the neighborhoods that become unaffordable” [9] Mitchell is right in that gentrification distorts neighborhood housing, displacing locals, and perpetuating wealth inequality. Using comparable listings from the 1990’s and today, one finds rents in Brooklyn have more than doubled in the past three decades [1,11]. Synchronously, average incomes of Brooklyn residents decreased by more than 13% [3]. These concurrent rent increases and income declines create a dynamic wherein the only non-native residents can afford to live in Brooklyn.

If one accepts the “minimize new development” position espoused by Mitchell, it is difficult to conceive of a middle ground allowing natural neighborhood progression. Mitchell would likely deem my father a gentrifier; my father will happily tell you that he was the BedStuy landlord to rent to the LGBTQ tenants, which while laudable, speaks to the change in BedStuy’s cultural fabric he has helped catalyze. Similarly, it’s naive to think father hasn’t contributed to the rise in rent that has made BedStuy unaffordable for many of his original neighbors. That said, how then can an areas residents profit through improving the local housing stock?

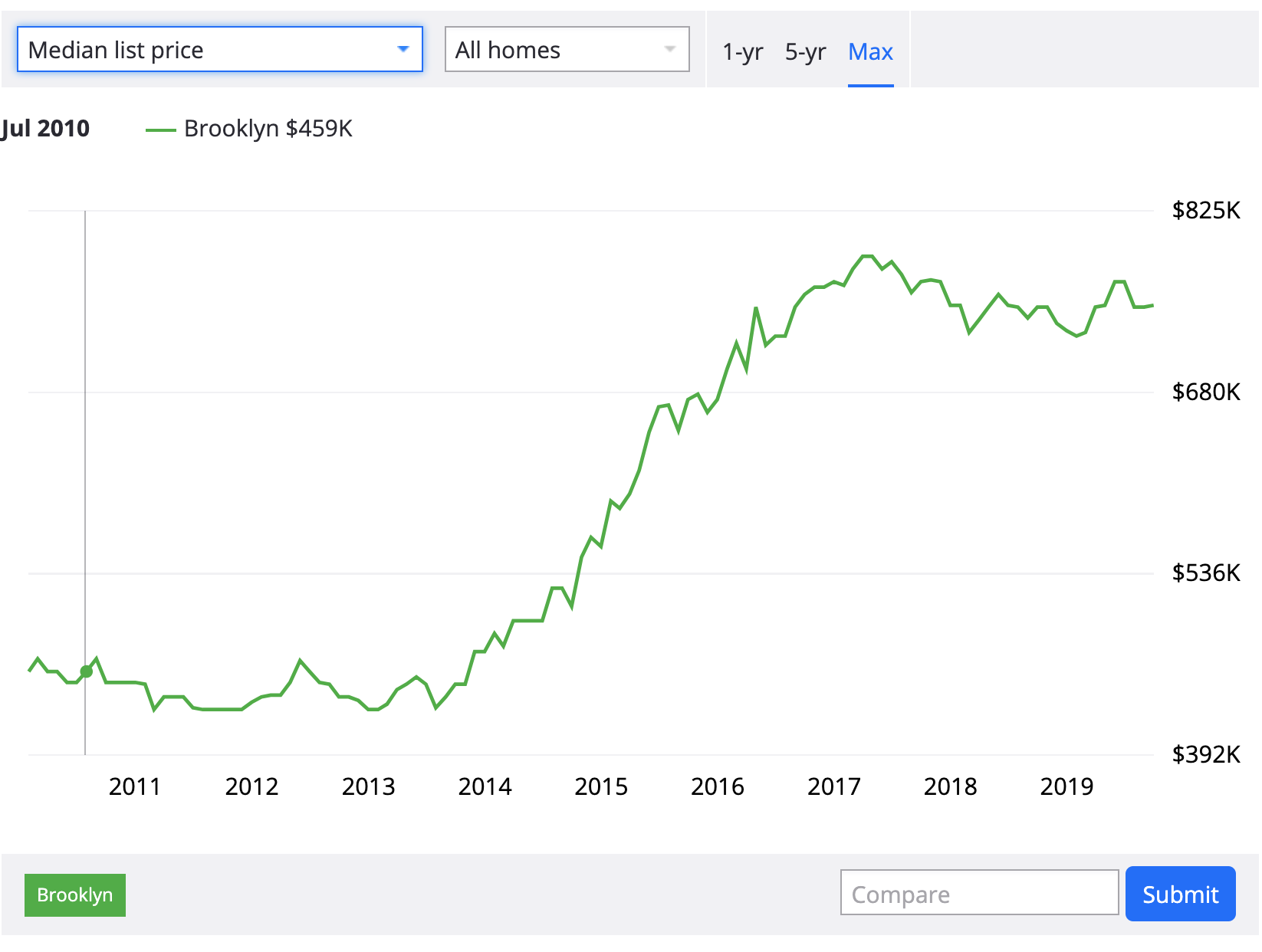

Housing Brooklyn housing price increase trends over last decade

NOLA has historically had a tumultuous relationship with gentrification, largely as a result of the city’s ethnographic makeup. Economically, NOLA is a city largely built on tourism. This is reflected in the ~$20 million in hotel tax revenue and $7.1 in tourism spending reported in the city’s 2019 budget [2]. The fairness of the distribution of the benefits of tourism between NOLA’s residents has been controversial, as Jeff Thought argues in his article for blacksourcemedia.com, “[NOLA] tourism, though unspoken, is largely afrocentric” [16]. The notion that the touristic appeal of NOLA is primarily due to its African inspired culture is difficult to fault; there is no doubt that the culinary and musical traditions that draw many to the city have distinct African influences. Unfortunately, while housing prices in the city continue to benefit from the city’s tourist appeal, NOLA’s black residents have not seen a commensurate rise in their incomes. In the last decade, median home prices in the city have doubled from $121,000 to $247,00, while average wages black residents have remained stagnant [8]. In effect, this means the people whose ancestors shaped the culture of NOLA are being priced out of the city.

While gentrification has been contentious in NOLA for quite some time, Hurricane Katrina was the largest single catalyst of gentrification in America’s history. In their analysis of gentrification’s determinants, van Holm et. al. found damage received during Katrina to be correlated to the likelihood of a neighborhood being gentrified in the ensuing decade.[18] Considering the city’s racial distribution and rebuilding efforts, this is unsurprising. Due to historically prejudiced banking practices, flood-prone neighborhoods like Gentilly and the Lower 9th Ward were more than 90% African American at the time of the storm[9]. This geographic segregation is evident when reviewing statistics of Katrina’s damage, where a black NOLA homeowner was three times more likely to lose their home than their white counterparts [18]. The unequal effects of the storm were exacerbated by the slow rebuilding of low income housing. HANO provides accommodation for just 35% of the residents it did pre-Katrina, even though the number of applicants has grown[19]. Logistical and economic difficulties faced by lower income residents in abandoning then returning to their neighborhoods further compounded their hardship. As journalist Nora Daniel’s notes in her series “It’s the symptom, not the cause,” the Lower 9th Ward was the last neighborhood to be deemed safe or have electricity restored. The city also adopted a form of “shock” austerity, cutting thousands of lower income municipal jobs [7]. As a function of geographic segregation, Katrina disproportionately damaged New Orleans’s lower income black communities, which were further disrupted by the city’s lacking rebuilding efforts, allowing the storm to act as an accelerant to the forces of gentrification.

NOLA has made efforts to combat gentrification through several of economic tools like the Low Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) as well as zoning legislations. According to reports from the Congressional Research Service, the LIHTC is the most widely used housing tax credit in the nation, funding the creation of over 2.2 million units of low income housing. [0] Additionally, NOLA’s Smart Housing Mix ordinance employs elements that have proven successful in New York and San Francisco. [7] The NY neighborhood of Greenwich Village is a prime example of effective neighborhood preservation initiatives. Community groups and City Council representatives fought for legislation preventing alteration of any historic facades in the neighborhood, forever preserving the lowrise brownstones and former factories that distinguish the architecture of the “The Village” from that of the larger city. [4] San Francisco, too, has found success in combating gentrification, mainly through the proliferation of housing vouchers and requiring new developments to have a specific ratio of units designated as affordable housing. Since the implementation of the combined programs, the San Francisco Housing Authority has reported a “meaningful” improvement in the availability of low income housing. [7] A synthesis of the protective zoning and mandatory new low income unit policies strategies employed by NY and San Francisco could benefit NOLA, which still has less than 47 affordable rental units per 100 low income residents [5].

The spread of gentrification in NOLA is nearing a crisis state, requiring a pro tem measure to slow progress while more permanent solutions are implemented. An immediate aid would be to raise a tax that contributes to the city’s Section 8 program, administered by HANO. This solution would be functionally similar to the San Francisco’s increased distribution of housing vouchers. The waiting list for Section 8 vouchers in NOLA is decades long and open only for a brief window every seven years. Recently, HANO has faced difficulty in receiving federal funding for its initiatives [19]. By levying taxes on high end rental units, Air BnBs, and hotel rooms, the city would be able to better fund HANO. A better funded HANO would in turn be able to pare its waiting list, proliferating affordable housing and slowing gentrification. While tax hikes are a difficult pill to swallow, increasing the availability of housing vouchers has proven to be successful tactic against gentrification.

In the long run, to combat gentrification NOLA lawmakers need to implement further zoning controls and promote greater community activism. While the Smart Housing initiative was a sign of progress, it is not comprehensive. Cities like NYC have been able to protect neighborhood cultures through protective zoning decisions and active community input. Residents in NYC China Town fought to establish a “Special District” to “maintain the neighborhood’s affordability for low-income immigrants, including limiting density in some areas, while encouraging affordable housing development in others” [15]. Additionally, as previously mentioned, community activists in NYC’s Greenwich village have passed legislation that protects architectural character of the neighborhood. NOLA would be wise to adopt similar zoning schemes and ordinances, protecting both the architectural and socioeconomic character of neighborhoods from gentrification.

Sources:

[0] 2019 United States, Congress, Keightley, Mark P. “An Introduction to the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit.” An Introduction to the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit.

[1] “ Apartments for Rent in Brooklyn NY.” Apartments.com, 25 Oct. 2019, www.apartments.com/brooklyn-ny/1-bedrooms/.

[2] “2019 Annual Operating Budget .” NOLA .com, City Of New Orleans, 1 Jan. 2018.

[3] Bergad, Laird W. “Trends in Median Household Income among New York City Latinos in Comparative Perspective, 1990 – 2011.” Department of Latin American, Latino and Puerto Rican Studies, Lehman College , Oct. 2013.

[4] “About Us.” Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation, 13 Oct. 2019, https://www.gvshp.org/_gvshp/about/mission.htm.

[5] Brown, Anitra D. “NEW ORLEANS’ AFFORDABLE HOUSING CRISIS:” The New Orleans Tribune, theneworleanstribune.com/new-orleans-affordable-housing-crisis/.

[6] Christie, Les. “Foreclosures up a Record 81% in 2008.” CNNMoney, Cable News Network, 15 Jan. 2009, money.cnn.com/2009/01/15/real_estate/millions_in_foreclosure/.

[7] Daniels, Nora. “It’s the Symptom, Not the Cause .” ViaNOLA Vie, ViaNOLA Vie, 28 Jan. 2019, www.viaNOLA vie.org/2019/01/28/its-the-symptom-not-the-cause-brad-part-1/.

[7] Kalugina, A. (2016). Affordable housing policies: An overview. Cornell Real Estate Review, 14(1), 76-83 . Retrieved from http://scholarship.sha.cornell.edu/crer/vol14/iss1/10

[8] Langston, Abigail. An Equity Profile Of New Orleans . PolicyLink and PERE, 2017, nationalequityatlas.org/sites/default/files/EP-New-Orleans-june21017-updated.pdf.

[9] Lower 9th Ward, New Orleans, LA Demographics. Areavibes, www.areavibes.com/new+orleans-la/lower+9th+ward/demographics/.

[9] Mock, Brentin. “Is Gentrification a National Emergency?” CityLab, 5 Apr. 2019, www.citylab.com/equity/2019/04/where-gentrification-happens-neighborhood-crisis-research/586537/.

[10] Ravo, Nick. “New York Housing: Sellers Finally Sell.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 26 Feb. 1995,https://www.nytimes.com/1995/02/26/realestate/new-york-housing-sellers-finally-sell.html.

[11] Rothstein, Mervyn. “New York Apartment Rents Moving Up.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 27 Feb. 1994,

www.nytimes.com/1994/02/27/realestate/new-york-apartment-rents-moving-up.html.

[12] Rivlin, Gary, et al. “White New Orleans Has Recovered from Hurricane Katrina. Black New Orleans Has Not.” Talk Poverty, 11 July 2019, talkpoverty.org/2016/08/29/white-new-orleans-recovered-hurricane-katrina-black-new-orleans-not/.

[13] Savitch-Lew, Abigail. “Chinatown Zoning Plan Meets Resistance in De Blasio Administration.” City Limits, 2 Nov. 2016, https://citylimits.org/2015/09/15/chinatown-zoning-plan-meets-resistance-in-de-blasio-administration/.

[14] Schulman, Sarah. The Gentrification of the Mind: Witness to a Lost Imagination. California University Press, 2013.

[15] “THE $1 BILLION QUESTION REVISITED.” Bureau of Governmental Research, Apr. 2019, www.bgr.org/wp-content/uploads/BGR_1BillionQuestionRevisited.pdf.

[16] Thoughts, Jeff. “Why Gentrification Is Especially Bad for New Orleans.” Black Source Media , 10 Feb. 2019, blacksourcemedia.com/why-gentrification-is-especially-bad-for-new-orleans/.

[17]United States, Congress, Keightley, Mark P. “An Introduction to the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit.” An Introduction to the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit.

[18] van Holm, E. J., & Wyczalkowski, C. K. (2019). Gentrification in the wake of a hurricane: New Orleans after Katrina. The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 56(13), 347–372. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-856X.00110

[19] Webster, Richard A. “HANO to Open Section 8 Wait List, Accept New Applicants.” NOLA .com, Times Picayune , 26 Feb. 2016,

[20] Webster, Richard A. “New Orleans Public Housing Remade after Katrina. Is It Working?” NOLA .com, 21 Aug. 2015, www.NOLA.com/news/article_833cc3f5-2d6d-5edc-bc0f-ecd55ead7026.html.

NOLAbeings

Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings

Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

Data corner: Adobe Suite (create a PDF, social media graphic, presentation, edit a photo and video

Data corner is where you go to work with analytics and top tech skills. It takes on everything from PERL and SQL to Canva and Sprout Social.

Data corner: Adobe Suite (create a PDF, social media graphic, presentation, edit a photo and video

Data corner is where you go to work with analytics and top tech skills. It takes on everything from PERL and SQL to Canva and Sprout Social.

[…] Many connected these raids to the gentrification sweeping the city since hurricane Katrina in 2005, recently described by Joseph Chanoff. As in many other American cities, working class residents, especially people of color, are being […]