Gentrification is defined as “the arrival of wealthier people in an existing urban district, a related increase in rents and property values, and changes in the district’s character and culture.” The term was coined in 1964 as Ruth Glass noticed that “the whole social character of the district is changed” when a class higher than the original population started to move in and take over.

Gentrification is especially pertinent in large cities like New York, where wealthy people flock to it, and landlords want to take advantage of their available wealth. In 1993, New York State legislators “passed loopholes into laws” that allowed landlords to turn their rent-stabilized apartments into market-rate ones by increasing the rent each time a tenant moved out until the rent hit a threshold, making it lose its rent-stabilized status. The term is often regarded negatively, but the area technically benefits as it sees more economic activity, reduced crime, and more investment in infrastructure. However, these benefits impact people disproportionately, and the original residents are economically and socially marginalized.

With wealthy people and powerful businesses moving in, there is no room for the population that originally made up an area. In America, gentrification appears in the form of white people taking over space where black people have historically existed. While this phenomenon has varying repercussions, the term is almost always negatively charged, and positive aspects are not acknowledged. Observing gentrification holistically will mitigate its damaging factors without unnecessarily removing or revamping the entire idea.

One positive aspect of gentrification is that it brings investment to communities that may be neglected and can lead to more jobs and businesses. Lance Freeman, the director of Urban Planning at Columbia University, explains that gentrification brings “full-service supermarkets that carry fresh produce, restaurants where residents could dine in, and well- maintained parks.” While there are certainly positives, brands like Starbucks are an example of harmful gentrification that bring negative repercussions to a community. There are 240 locations in Manhattan alone taking up space that used to belong to small businesses and driving up prices. The severe increase of chains, like Starbucks, have moved in to satisfy what the industry assumes residents want. Small cafes could be welcomed into neighborhoods to bring diversity to cities and turn the situation into an example of positive gentrification.

Claiborne Avenue in 1966, pre-renovation

Gentrification is an issue present all across New Orleans, and one prominent example is the development of the Claiborne Overpass. It is a highway connecting uptown New Orleans to downtown, replacing the once lively, bustling hub of black culture in the city. In a country where segregation only ended in 1964, areas that catered to black residents were essential in allowing them to establish roots and feel comfortable in America. The overpass was part of the Federal Highway Act of 1956, which originally included a plan to build new infrastructure in the predominantly white French Quarter neighborhood as well. Rich and powerful white residents combatted this part of the plan, and their area was preserved. The residents near Claiborne were not so lucky, and “many in the Treme neighborhood weren’t even aware of the plan… and officials didn’t bother consulting with local residents.” This was devastating for black residents because Claiborne Avenue “served as a center of New Orleans’ Black economic and cultural life” until construction began in the late 1960s, and the overpass eventually opened in 1969. One former resident of the area, Dodie Smith-Simmons, is now a local civil rights activist. She detailed growing up near Lavada’s, an oyster house she would frequent with her friends. The property is now a parking lot. Lavada’s is not unique in the fate it suffered; the 123 businesses that stood in 1950 on Claiborne have dwindled to only 44 just 50 years later. Another former resident, Edgar Chase III, said in response to the displacement the community members experienced, “When you uproot something, it’s hard to plant it someplace else and for it to survive.” The destruction of this iconic neighborhood halted the community’s financial uprising and continued the historical precedent that black people’s lives and needs are less valued than white people’s. Dookie Chase states how it reinforces the power dynamic in a city: “Power doesn’t flow to those who really need it, but it flows to those who are a certain color who already have the power.” It is hard to find anything fair about such blatant inequality in a city that prides itself on its abundance of black culture.

The solution to gentrification is complicated because it involves social, financial, and structural components. Not only this, but gentrification is nearly impossible to reverse in a way that would satisfy the old inhabitants of a city and the new ones, as the cultural and physical makeup of a place takes years to change. Instead, the main solution would be to learn from history and develop a new legislature to prevent those patterns from repeating. One solution would be to implement zoning laws that make living in a particular place affordable for citizens of all economic backgrounds.

Wealthy people flock to their vacation homes or luxury residences across low-income cities in America. Bend, Oregon is one such city that faced that fate but was challenged when Governor Kate Brown “signed a law that requires most Oregon cities with more than 1000 residents to allow duplexes in areas previously zoned exclusively for single-home families.” The law would prevent single families from taking massive shares of land that have the potential to be inhabited by more residents. That allows for more economic and racial diversity in each city. Increasing population density also allows there to be more customers to support businesses and people to create a community. The legislation addresses historic inequities that led to “racial and economic segregation and displacement in neighborhoods.” This law was part of a larger legislative package that aimed to create more affordable housing in Bend along with rent control measures and fewer restrictions on creating accessory dwelling units (ADUs). Once the legislation was implemented, the city’s population doubled over the next twenty years and will continue to increase through 2030.

A graphic rendering of the NorthWest neighborhood, courtesy of artist Martin Kyle Milward

The legislature’s success partly relied on having the proper support from communities and organizations like the AARP, which wanted to create housing options for older adults who didn’t want to move neighborhoods. Another organization, Habitat for Humanity, committed to building duplexes and triplexes in areas that were historically zoned for single-family houses. Citizens expressed concern that the livability of the new infrastructure would be poor and their expectations of quality would not be met. However, a city planner, Damian Syrnyk, mitigated these worries by confirming there would be high-quality designs that “can have a similar footprint as neighborhoods stocked exclusively with single-family homes.” This design is seen in the NorthWest Crossing neighborhood, dominated by single-family homes and “townhomes, affordable apartment complexes, senior living centers, and ‘cottage clusters’, smaller groupings of single-family homes…”. This structure has “led to a community that better reflects the demographic composition of the area.” Bend’s Mayor, Sally Russell, considers the city’s improvements to be a model for other places that want to preserve economic and racial diversity while improving infrastructure and quality of living.

This solution has proven effective, but there is concern that the observed growth has been occurring too rapidly. Some residents called for a moratorium on development because there was an increase in traffic and general congestion in the city. City planners met these complaints with a public conversation about what people wanted to see done to overcome these challenges. An essential part of mitigating these challenges was incorporating more streets, parks, and schools into the city so the population density did not overwhelm the resources that were available. Roundabouts were introduced and satisfied residents because they avoided the need for five-lane roads and intersections that would interfere with the character and aesthetics of the city. Another issue the city is still working on is lowering the median price of housing. While their plan has created more options than were previously available, the real estate market in Bend has skyrocketed because of their improvements and has increased prices as a whole. One worker, Kirk Schueler, said “efforts to deliver affordable housing have not been successful.” That statement counters the ones made by Governor Brown, but she likely meant the pricing was more affordable than it has been in the past. Clearly, Bend still needs more work, but their improvements outshine the efforts, or lack thereof, of cities across the country. Bend will continue its mission to make housing more affordable in the coming years.

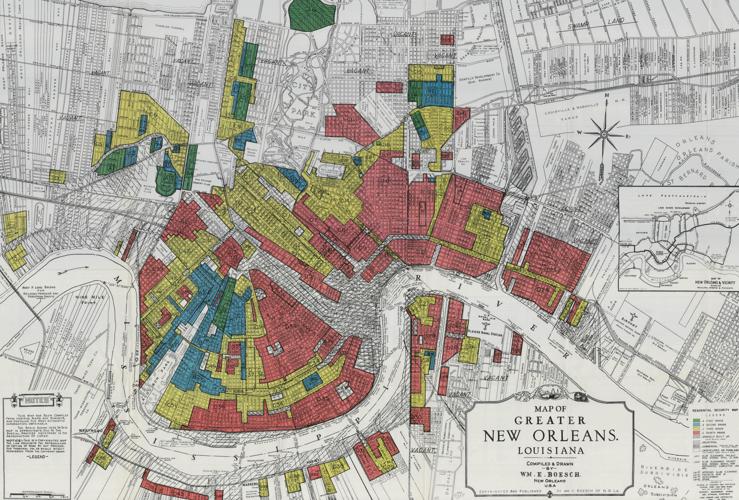

A map of New Orleans redlining plan, with colors representing Type A-Type D

The city of New Orleans has historically had severe redlining, with neighborhoods of black, poor, and working-class people being deemed “Type D”, the lowest regarded category. These practices have had lasting impacts, and the uptown areas remain populated with a majority of white, rich people, while the downtown areas are populated with more black people. From 2000 to 2016, the percentage of African-American residents in the Irish Channel plummeted from 75% to 27%. Implementing the legislation regarding new zoning to allow duplexes in areas historically used for single-family homes would give lower-income residents a chance to live in an area with a variety of job and schooling opportunities. Cashauna Hill, director of the Greater New Orleans Fair Housing Action Center, said “We often hear from uninformed people that the market determines where people live, that segregation occurs because of choices people make.” Clearly, this is not true, and the population needs the opportunities to move into these areas that can only be made possible by government interference. One resident, Shawanda Holmes, wakes up her six-year-old son at five AM to place him on a bus that drives an hour to his school uptown. This way of living is unsustainable, and Holmes certainly did not choose this situation. Instead, she was required to relocate because of the dangerous lead found on her previous property.

New Orleans administrators have been working on changing their zoning to make housing affordable in all areas, and one project that has already been implemented is The Muses Apartments, which has 65% of the units set at market rate and 35% set for residents with low-income tax credits. This allows people of diverse economic backgrounds to take advantage of the same housing opportunities and reap the benefits of living in the same area. The model is not yet widespread, partly due to the cost of implementing affordable housing. The Muses project utilized $7 million on four acres of land; those numbers are not practical for restructuring an entire city. Along with the financial aspect, affordable housing projects will face a social roadblock. One of the ideas proposed by Mayor LaToya Cantrell’s administration was to provide voluntary affordability options, yet it may be unreasonable to expect landlords to create affordable options to give back to the community when they could instead be generating more profit for themselves.

Looking beyond the culture of greed ingrained in the housing and living processes, getting city planners and administration involved in the housing and gentrification issues may be the most effective way to avoid displacement while diversifying and improving communities. If neighborhoods and government officials are willing to work together to envision a new, more cohesive society, people from all backgrounds will be able to benefit from the changes that areas face as society evolves.

This piece was edited by Anna Blavatnik as part of Professor Kelley Crawford’s Digital Civic Engagement course at Tulane University.

Sources:

Woodward, Alex. “How ‘redlining’ Shaped New Orleans Neighborhoods — Is It Too Late to Be Fixed?” NOLA.Com, 16 Dec. 2021, www.nola.com/gambit/news/article_215014ce-0c15-5917-b773-8d1d2fdaa655.html.

Gershon, Livia. “The Highway That Sparked the Demise of an Iconic Black Street in New Orleans.” Smithsonian Magazine, 28 May 2021, www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/documenting-history-iconic-new-orleans-street-and-looking-its-future-180977854.

Tol, Jesse van. “Yes, You Can Gentrify a Neighborhood without Pushing out Poor People.” Washington Post, 8 Apr. 2019, www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/2019/04/08/yes-you-can-gentrify-neighborhood-without-pushing-out-poor-people.

Price, David. “7 Policies That Could Prevent Gentrification.” Shelterforce, 18 Oct. 2021, shelterforce.org/2014/05/23/7_policies_that_could_prevent_gentrification.

“‘The Monster’: Claiborne Avenue Before And After The Interstate.” WWNO, 5 May 2016, www.wwno.org/podcast/tripod-new-orleans-at-300/2016-05-05/the-monster-claiborne-avenue-before-and-after-the-interstate.

“History of Gentrification in America: A Timeline | Next City.” Next City, nextcity.org/history-of-gentrification#in1994. Accessed 7 May 2022.

“Gentrification Doesn’t Have to Force Minority Residents out of Their Homes. Activists Say There Are 3 Ways to Protect Communities.” Business Insider, 28 Sept. 2020, www.businessinsider.com/personal-finance/how-to-protect-longtime-residents-from-gentrification-2020-9?international=true&r=US&IR=T.

“Affordable Housing Push Challenges Single-Family Zoning.” The Pew Charitable Trusts, 20 Aug. 2019, www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/blogs/stateline/2019/08/20/affordable-housing-push-challenges-single-family-zoning.

“NorthWest Crossing in Bend, Oregon : UnSprawl Case Study : Terrain.Org.” Terrain.Org, www.terrain.org/unsprawl/18. Accessed 7 May 2022.

“Gentrification in Portland: Residents and Readers Debate.” The Atlantic, 15 August 2016, https://www.theatlantic.com/national/archive/2016/08/albina/623360/

NOLAbeings

Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings

Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

Data corner: Adobe Suite (create a PDF, social media graphic, presentation, edit a photo and video

Data corner is where you go to work with analytics and top tech skills. It takes on everything from PERL and SQL to Canva and Sprout Social.

Data corner: Adobe Suite (create a PDF, social media graphic, presentation, edit a photo and video

Data corner is where you go to work with analytics and top tech skills. It takes on everything from PERL and SQL to Canva and Sprout Social.