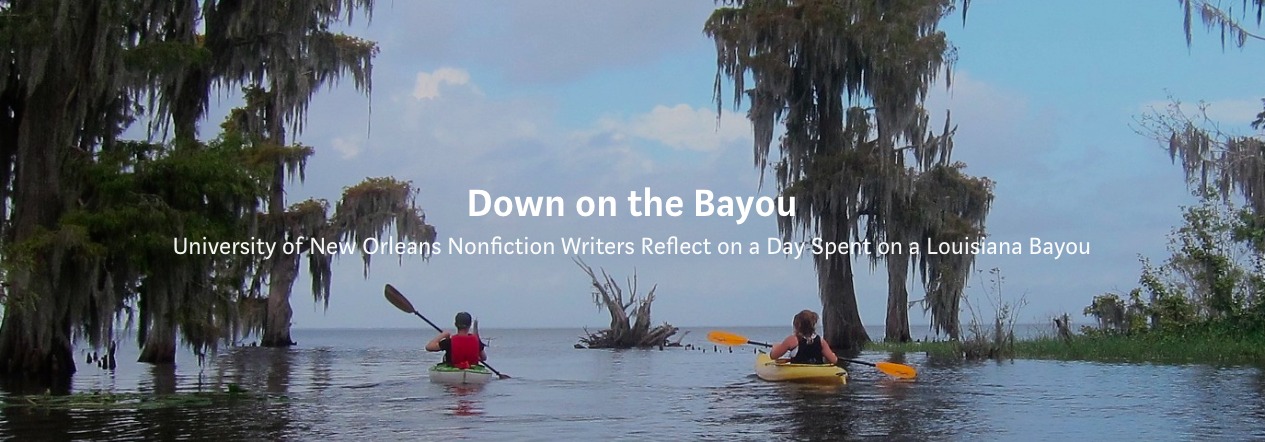

Students kayaking down the bayou for Richard Goodman’s MFA course. (Photo from: Down the Bayou website)

Editor’s Note:Christine Baniewicz took part in Richard Goodman’s Master of Fine Arts nonfiction writing workshop at the University of New Orleans, where the students take a kayak trip down a southeastern Louisiana bayou in order to observe the issues and conditions that make the bayous beautiful and precarious. Once they finish their full-day kayaking adventure, the students reflect and write, creating pieces that encapsulate their experience and give new awareness about the bayous. ViaNolaVie will be running these pieces as a continued series every week, and you can also read more student writing here and here. And now for Christine Baniewicz’s “Water Hyancinth.”

Christine Baniewicz , writer and MFA student at UNO. (Photo provided by: Christine Baniewicz )

If you’ve ever boated down a Louisiana bayou, you’ve seen the water hyacinth. It’s everywhere, hardy spade-shaped leaves upturned, blanketing the still black waters between the cypress stags and tupelo trees. An invasive species, native to Brazil and originally introduced to the Louisiana wetlands at the 1884 New Orleans World’s Fair, it was prized for the exceptional beauty of its blossoms. However, the water hyacinth has since taken over the lowland swamps, a nuisance to anyone interested in piloting even the skinniest vessel through the shallow brackish water.

Thanks to its waterlogged estuary environment, the water hyacinth can’t be controlled with pesticides, which work like soap to break down the protective compounds on a plants’ leaves, coating their entire surface with poison. Unfortunately, such pesticides have the same affect on amphibians, insect larvae, anything wet-skinned and alive that may be on the premises.

So the water hyacinth thrives, the bayou’s profligate ground cover, tangled black roots clumping together beneath the water’s surface. Looking out across the marshland from my plastic kayak, I try to imagine the swamp without it.

I can’t.

– – –

I have been an anxious person for most of my life. Even at my happiest, laughing and smiling and chatty, engaged in joyful activities with friends and loved ones—even then, I tend to be simultaneously grappling just under the surface with some worried, invasive thought.

I can’t say for sure if this habit of the mind is native, or was introduced at a young age by my parents, also chronic worriers. At any rate, the tendency has taken hold of my brain with alarming tenacity. My anxious thoughts clump together, making it hard to navigate any straightforward course of reasoning without extraordinary patience and muscle.

I’ve tried all the traditional methods of anxiety management: Soothing music. Yoga. A cup of hot tea. Guided meditation and brisk jogs and alternate nostril breathing. While these measures often do manage to clear out a little pocket of open space in my mind, they just as often prove tedious and partial. The worried thoughts grow back. Or I try to continue on my way and find myself mired in a completely new set of thoughts just moments later, cursing my luck, frustrated, tired and blocked.

I have never even tried to imagine my life without it.

– – –

On the morning of Saturday, October 21st, as I paddled a tandem kayak through the bayou with my tour guide, Owen, and a dozen other writers, I worried about a conversation I’d had with my fiancé, Chanel, a couple of days earlier.

On the surface, I seemed calm. I quizzed Owen about the landscape. What’s the name of that jet-blue dragonfly? I asked. My colleagues and I had come out, after all, for a hands-on education about Louisiana’s endangered wetlands habitat.

So I made the most of my knowledgeable guide. Beneath the surface, though, I worked over and over the content of my most recent conversation with Chanel. We are both somewhat conflict-averse, and our arguments, no matter the topic, often go something like this: I’m critical. She’s hurt. I’m remorseful and she withdraws. I panic, afraid she’s preparing to leave me, and then she panics, sure that she’s letting me down somehow by feeling sad. Our anxieties spiral around and around and around until neither of us can remember what had even gotten us started in the first place.

To make matters worse, I’d subconsciously believed that our recent engagement would magically resolve this dynamic. Unfortunately, it had only intensified. The stakes were now higher. The slightest disagreement had us reeling. We spiraled, gripping at one another’s hearts, setting more and more rules and mandatory phone dates and check-ins. In my darkest moments, I’d begun to think wistfully back on the disastrous relationships and long lonely stretches of my early twenties. I photo-touched all of those memories in my mind, adding light and ease and laughter and deleting all the despair and then I’d play the old movies back to myself as I lay in bed at night, wondering how I’d managed to get myself so trapped and unhappy since then.

I paddled and worried and paddled. This is gonna destroy our relationship, I thought. This thought quickly gathered a clump of busy, related thoughts all around it. I am a bad person, I will never find love, I will die alone.

Meanwhile, Owen and I piloted our kayak into dimmer, narrower passageways in the bayou. We ducked beneath the burnt-grey beards of low-hanging Spanish moss. The open waterway shrunk down to a fifteen-inch passage, shallow enough for the bottom of our vessel to catch the mud in places, crossed with fallen logs and hemmed in on each side by dense patches of water hyacinth and alligator weed. Here, the sulfurous scent of the swamp hung thick. Disturbingly large mosquitos materialized, alighting on my neck and shoulders and ankles as Owen and I grunted and shoved and forced our way through the watery thicket.

Earlier, Owen and I had managed to establish a rhythm, syncing up our paddle strokes on each side of the boat. Here, however, so impeded by foliage, we lost our groove. Our separate paddles struck and crossed. Sorry, sorry, we kept saying. The going was slow. Clumps of the water hyacinth came up with my paddle on the fore stroke, dripping stinky water all over my shoulders.

I lifted the paddle and worried: I shouldn’t have said that thing I said. I dug it in: I’ve ruined Chanel’s life. I forced the kayak forward: She’s gonna leave me. Repeat: I shouldn’t, I’ve ruined, she’s leaving. Shouldn’t. Ruined. Leaving.

Just then, a clump of water hyacinth snagged on my paddle, and I had to forcefully shake it off. “This fucking plant.”

“I know, right?” said Owen from behind. “Go back to Brazil.”

– – –

Chanel once told me that folks used to spray the whole bayou with arsenic in the hopes of killing off the water hyacinth. I don’t know what the results were on the biota as a whole, but I can’t imagine they were positive.

Likewise, I can’t just nuke my anxiety away. Drinking too much, distracting myself with work, attempting in any number of ways to fully suppress my worry usually results in the deadening of everything else going on in my mind. It zaps my humor and creativity, my intuition, my memories, and the weird unknowable processes by which ideas gestate and co-mingle in the intricate, fragile ways that lead to stories and essays.

My worried thoughts are a part of the ecosystem of my mind. They’re annoying and invasive but that’s my situation. I gotta work with it. And as long as Chanel wants to be with me, she has to work with it, too. That’s the deal with relationships: one boat, two paddles, and a whole lotta shit that you can’t send back to Brazil.

– – –

When at last the narrow passage widened, Owen and I skimmed our way gratefully through a few winding, open bends of the bayou. The cypress trees thinned out and the water shaded to silver, reflecting the overcast sky. Out beyond the tree line, Lake Maurepas stretched undisturbed towards the horizon.

Most of the others in our group had snagged single kayaks, and took the opportunity to paddle away from the group and meditate alone on the natural beauty of the lake. I envied them a little. Despite the abject misery of my thoughts, a part of me wanted to be alone with them anyway.

Eventually, though, Owen and I decided to paddle together out to the farthest cypress tree we could find in the open water. It was forty-feet tall and leafless in the late autumn, towering over us. We slowly brought the boat around to the base of the trunk. With Owen’s extra weight to stabilize the kayak, I was able to reach out over the lip of the boat and touch the smooth, feathery grey bark of a tree that we guessed was at least a hundred years old.

– – –

When Chanel and I are both a hundred years old, our skin thin and worn, we’ll still spiral sometimes. I’ll get scared and feel alone. She’ll get scared and feel sure she’s messed up. We’ll grip each other’s forearms just a little too tightly on the armrests of our wheelchairs.

Hopefully, though, we’ll have learned by then how to breathe and talk our way through it. Hopefully, Chanel will croak at me from her wheelchair, Remember all that shit back then, before we got our asses into therapy? I’ll lean closer, turn up my hearing aid. What?

Hopefully, by the time we’re as old as that cypress tree in Lake Maurepas, the power of our hard-earned love will tower over everything else. It will dwarf our myriad flaws and mistakes. It will be the biggest, prettiest thing there is to see for miles.

– – –

On the way back from the lake, it began to rain. A cold, steady rain. Fat drops.

As Owen and I approached the narrows again, this time from the other side, we quieted. Together, we stabbed our paddles into the reeds. When one or the other of us got tangled up, we waited. We re-synced. We plunged ahead.

Behind us, those in solo boats struggled to direct themselves, sweat sticking out on their brows, alone in their fatigue and frustration.

But Owen and I bantered. We joked. For brief moments, we felt like one organism, strong and focused on our singular task. For brief moments, I didn’t think at all. I just rowed, just listened to the tack of the rain against my poncho and watched the water pool and bead down the surface of the elephant ears at the edge of the water.

I just made the passage I needed to make, one moment at a time.

And there are moments with Chanel, too, where I feel us hit our stride. I grade papers at the kitchen table while she cooks something hearty and filling. Or we soak together in the bathtub while I rub the arch of her foot, listen as she sighs, as the ice clinks against the edge of her whiskey glass. Or when we sit together on the front porch in the morning and look out across the neighbor’s hayfield and wordlessly keep the company of the songbirds and the oak trees and the cool air of the new day all around us.

In those moments, I don’t think much of anything. I just feel happy.

– – –

When Owen and I got near the end of the narrowest section, I stopped rowing.

“Hey, look,” I said.

On the left side of the kayak, one of the water hyacinths was in bloom. Its flower was lavender, shaped like an iris, with a silver-dollar-sized blossom and a yellow throat.

“Wow,” said Owen.

I smiled. “It’s so pretty.”

Later, on our final passage out of the bayou, I noticed a whole stand of water hyacinths in bloom at the edge of the water, dozens of them purpling a far bank. Owen and I coasted by, gazed at them in wonder. Most of the water hyacinths we’d passed that day had not been in bloom. They were thick and green and alive, but they were not exceptionally beautiful.

Most of my thoughts are not exceptionally beautiful. The vast majority of them are ordinary: I should exercise more, my hair looks good today, that’s a cool billboard. Some of them are invasive and troubling: I’m a bad person, I don’t deserve happiness, my partner doesn’t love me anymore. These are the ones I spend most of my time working to get beyond, to beat back with patient lines of reasoning or take with Chanel in to our therapist on Mondays. Our very own thought-doctor, our very own wilderness guide.

Every now and again, though, a thought or two of mine will open itself up, a delicate and mesmerizing thing. My mind is like the swamp, I’ll think. These thoughts are like the water hyacinth. Those are the ones I try to slow down for, to carefully observe, to clip and arrange on the page. And no matter how exhausting it was to get there, I’m always grateful for them, each vibrant, living, exceptional blossom of thought.

Christine Baniewicz is a freelance writer, part-time food service professional and former fellow at the San Francisco Writers’ Grotto. She lives in Lafayette, Louisiana with her partner, Chanel, their ginger cat, Panko, and lots of errant thoughts.

New Orleans Startups

A brief overview of the growing New Orleans startup scene. This piece highlights the main industries of New Orleans, competing cities, and just how emerging the current entrepreneurial/startup scene is in New Orleans.

New Orleans Startups

A brief overview of the growing New Orleans startup scene. This piece highlights the main industries of New Orleans, competing cities, and just how emerging the current entrepreneurial/startup scene is in New Orleans.

A Bin in Every Classroom: Why Tulane Should Lead on Composting

I asked a peer, Isabel, for her thoughts on composting: “Why do...

Tulane

A Bin in Every Classroom: Why Tulane Should Lead on Composting

I asked a peer, Isabel, for her thoughts on composting: “Why do...

Tulane