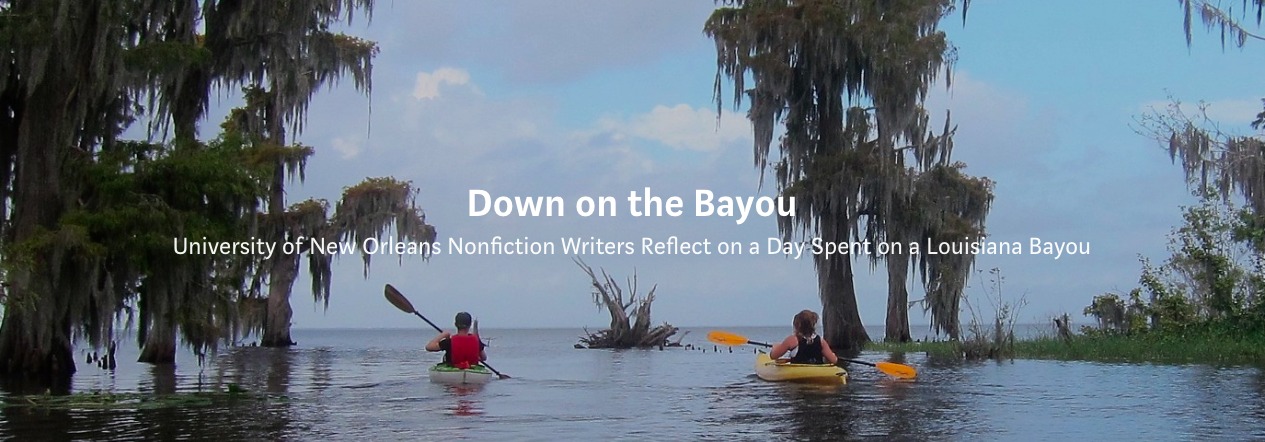

Students kayaking down the bayou for Richard Goodman’s MFA course. (Photo from: Down the Bayou website)

Editor’s Note: Jake Bundez took part in Richard Goodman’s Master of Fine Arts nonfiction writing workshop at the University of New Orleans, where the students take a kayak trip down a southeastern Louisiana bayou in order to observe the issues and conditions that make the bayous beautiful and precarious. Once they finish their full-day kayaking adventure, the students reflect and write, creating pieces that encapsulate their experience and give new awareness about the bayous. ViaNolaVie will be running these pieces as a continued series every week, and you can also read more student writing here and here. And now for Jake Bundez’s “Eventually, the Rain Stops.”

Jacob Bundez, writer and part of the MFA creative non-fiction workshop taught by Richard Goodman. (Photo by:Clare Welsh)

By the dining room window in Bob Marshall’s Mid-City home, a painted wooden statue of a one-winged baby hangs from the ceiling by thread too thin to see. The baby twirls slowly in the current of the air conditioning.

This city is sinking.

I’ve heard people who live in New Orleans repeat different iterations of this phrase many times, before Bob’s talk on the ways humankind’s attempts to control nature have caused the Gulf of Mexico to creep further and further up the coast, swallowing wetlands in its path.

“Welp, we do live in a sinking city,” I’ve heard people say — with the same tone of fond resignation they use when they talk about getting caught in parade-related traffic during Mardi Gras, or getting caught in a downpour while biking to the grocery store in August. Yeah, there’s potholes in the road, but that’s just because it’s a sinking city. With a shrug. As if to say, “hey, that’s just our kooky city, where public schools close for the whole week of Mardi Gras, where winged termites swarm porch lights as early as May, and where the disappearing coastline caused by levees, canals, and climate change will eventually displace us all.”

Well, not all of us, of course.

As Bob jokes during his presentation, my classmates and I can all leave as soon as grad school is over, so why should we care? I don’t believe he’s saying this to make us feel guilty; and yet, the heavy weight of conviction pulls my forehead down until my head is bowed, as if in prayer.

This talk is the preface to a kayak ride out in the wetlands between Lake Pontchartrain and Lake Maurepas. Last night, at my friend’s Halloween party — the first time in weeks that I’d left the house to do anything other than chip away at the endless stream of deadlines I’ve waded through this semester — I thought about the rainstorm that threatened to cancel the day’s trip out to the bayou. I thought about the gig I had agreed to play just hours after the kayak trip was set to end. I thought about one of my many deadlines two days later and about the fact that I could count on one hand the amount of hours I’d slept in the past two days. I finished my drink and prayed for rain. This morning, I woke up and that grouchiness was gone. I was tired and, yes, a little bit hungover, but I stuffed my bag with enough protein bars for me and my classmates, looking forward to the day ahead.

Bob explains how over thousands and thousands of years, the Mississippi River dropped sediment that caused southern Louisiana to rise from beneath the Gulf of Mexico. In just a century or so, largely due to the levees that prevent that sediment from depositing on the river’s banks and the undeniably rising sea levels, the coast has begun to dip beneath the waves once more. Entire towns out in the wetlands, now, are underwater. Through the wonders of technology, Bob illustrates the difference between the Louisiana that was and the Louisiana that is. He shows us an image that displays the familiar boot-shaped state of Louisiana seen on every US map, tells us the last time it was updated was sometime in the 1930s. With the press of a button, the bottom of the boot is awash with bright red, indicating land loss since the 1930s. Red splotches cover southern Louisiana, like the boot is made of wood, and slow-but-steady termites are eating through it from the sole up.

The attempts to restore sediment to this beautiful, muddy state by removing levees in certain areas have begun to show promising results, but it’s not happening fast enough, and the project is slowly running out of money.

In other words, here’s what I internalize: it’s fucked. We’re trying our best, and it’s not enough.

As we pile into Christine’s old car, I’m trying not to draw parallels between the condition of southern Louisiana and the shitstorm my life has been for the past few months. I’m trying to refrain because it’s stupid and selfish and indulgent — comparing the plight of an entire state’s cataclysmic, not-so-natural disaster to my own petty emotional turmoil.

But the parallels are there, too obvious for me to overlook, because I feel like I’m fucked, too, even though I’m doing the best that I can. For starters, I’ve bitten off way more work than I can chew. Where the normal course load in my grad program is three courses, I’m taking four courses while also teaching a college class for the first time. There’s little to no breathing room with three courses when you’re teaching freshman-level English, but with four courses? I’m flooded, if you will, with work (har, har, har).

I’ve got a long-distance relationship that’s clearly straining under the weight of my stress. I’ve got a beloved relative who’s been diagnosed with a life-threatening illness, who’s all the way across the country — someone who’s always been in my corner that, now, I can do nothing for. I’ve got twice-weekly physical therapy for an injury from biking too much, which has hindered my ability to exercise, to walk more than a few blocks without severe leg cramps, or even to get around the city by bike as I’ve always done. I’ve got bus rides to teach three times a week at the crack of dawn, trying to recover some semblance of confidence and dignity after pretending I can’t hear the homophobic slurs muttered by glaring commuters around me. I’ve got the joys of nightly panic attacks resurfacing for the first time since I first went to therapy years ago, slashing my ability to sleep nearly in half.

I’m sure when I push through all of this (when, not if, goddammit) I’ll be proud of all the work I’ve accomplished, maybe a little embarrassed at how melodramatic my stress response has been. But right now everything feels heavy. Grave. Cataclysmic. Like water creeping slowly up the walkway, no discernible end to the pouring rain.

On the ride out to the bayou, things are lighter.

As five of us pile into Christine’s car, she makes self-deprecating jokes about how old and messy her vehicle is. We drive with the windows down, the perfectly temperate air swirling pleasantly through the car. There’s a kind of cynical camaraderie between my classmates and me in the car, in that we all feel fucked after that talk, and that we feel complicit in the ways we’re fucked. Somebody cracks a joke about hearing something so bleak at 9:00 AM on a Saturday. The driving directions say that the gas station by the bayou will be the last chance we have to use the restroom all day. “We’ll see about that,” I joke. “I have a bladder the size of a peanut.” At the gas station, I take a photograph of the glass case full of knives, which Christine jokes that people out here use for “cutting ropes and skinning homosexuals” (she and I are both gay). We all laugh too hard at the jokes, as if everything is hysterical right now. Relief. We all agree that right now, it feels like there’s nothing to do but laugh.

We pull off at the side of the road at a short stretch of beach, gravelly and unremarkable. Beyond it, a narrow corridor of shallow water squeezed between wet greenery. Where sand meets water, there’s a line of colorful and bright kayaks, as well as two very sweet men — Chris and Owen — who will be our guides out on the water. We have a brief rock-paper-scissors tournament among us to determine who gets their own kayaks and who has to share tandem kayaks.

Mercifully, I get my own.

“Um,” I address my peers. “Does anyone have a preference for kayak color? I mean…”

My classmate Reda, not missing a beat, says, “Are you asking because you want the lime green one? Because you can have it.”

Mystified, I wonder if she’s clairvoyant or if it’s just obvious how tacky I am. Probably both, I decide. I thank her.

I push my kayak into the water, and my professor, Richard, steadies it while I slither cautiously into the wobbling plastic vessel. As my paddle hits the water and I propel myself forward, I realize two things. One: that stress weighs me down like a backpack filled with stones. Two: that the weight is suddenly, inexplicably gone.

At first I don’t understand what’s so intoxicating about the water that even the thick concrete columns holding up the highway bridge feel majestic as they plunge into the brackish water from above. Later in the day, I will understand that with no way of solving the mountain of problems on my plate while I’m out in the water, I feel completely free of them. But for now I’m shrieking with laughter, grinning at how cute my classmates look in lifejackets and trucker hats, pointing and laughing at the knobby cypress knees poking through the surface of the water. “Whose knees are these?” Christine says as she and her tandem kayak mate, Owen, glide past me. My loud cackle bounces off the calm water and seems to brush against the hyacinth leaves that rustle in the breeze.

So we embark through the narrow passages toward the open waters of Lake Maurepas. I haven’t felt so giddy in months. I practically squeal at the sight of monarch butterflies and point out particularly thick patches of yellow flowers that pepper the otherwise uninterrupted walls of brown and green on either side of our waterway. I take excessive pleasure in sharing protein bars and sunscreen with my classmates (a large part of me, for some reason, finds joy in nurturing the people around me, especially when I myself am in emotional turmoil). My friend Betsy dubs me “kayak mom.”

Is it tedious, arduous work getting through the bayou? At times, absolutely. Mired in shallows thick with overgrown hyacinth, I have a solid half hour where each stroke takes every ounce of my (admittedly meager) arm strength, yet yields only inches forward in return. Here, the previously mild sun emerges from his cloak of clouds and beats against me with his unforgiving rays. Here, hordes of mosquitoes nibble at every inch of exposed skin, and I say aloud to myself, “This doesn’t feel cute anymore.”

But then I remember I have bug repellent, which I spray liberally all over myself. The mosquitoes leave me be. As I pass the spray to Reda in her kayak in front of me, assuring her that this DEET will change her life, I look around me. To my left and right, just below eye level, blankets of yellow flowers stretch as far as I can see. I’m not sure the species, but they remind me of marigolds or poppies, with three or four round yellow petals curling up toward the sky. They’re all I can see aside from the ubiquitous green of the water hyacinth, the cloudy sky, and a thin line of tall trees not too far ahead.

Who am I to complain?

I dig my paddle into the water that’s so thick with vegetation that it feels nearly impossible to move forward. I push.

Once we break through into a wider, clearer waterway, it’s not far at all to the lake. I fail to duck low enough under a branch that hangs so low across the waterway that it knocks my hat off. In reaching back to catch the hat, I crash into the tree, get caught in the weeds trying to paddle backwards away from it, and nearly capsize in the process. But for some reason, I’m not perturbed or frustrated in the least. I’m laughing so hard at myself I’m nearly crying.

One classmate asks me how I’m in such ridiculously high spirits, especially after we trudged through all that hyacinth.

“I don’t know!” I answer honestly, then joke: “I’m a water sign? We’re on the water? That must be it.”

I’d like to claim that when the trees finally part, giving way to open water, I have some epiphanic moment about moving through hardship and finally making it where you’re going. But honestly? I have to pee so desperately I’m just relieved we’ve arrived at a place I can do so. I’m too distracted for an epiphany, though I do marvel at the majesty of the lake as I pass the last cypress trees.

No, my real “moment” comes when my kayak flips over a half an hour later. There’s a mishap involving a bee, its fat stinger, a very panicked Jake — arms and paddle waving like a crazy person — and my classmates yelling, “careful, careful, you’ll flip!”

And then I’m in the water.

It’s just a little too cold to be pleasant, and there are two leeches on the bottom of my kayak, and I’m a little freaked out in these unfamiliar waters. But somehow, somehow this too is hysterically funny to me.

Our guide, Chris, paddles over to me in his tandem kayak with our professor Richard, as does Owen in his tandem with Christine. I hang off Richard and Chris’s boat as they paddle me to shallow water, and Owen and Christine pull my kayak to us. Absurdly, I’m more concerned with the litter that was in my boat than anything else — I make frantic grabs for the discarded wrappers of Skittles and protein bars that float on the surface around me. I don’t know. Probably residual guilt from this morning at how screwed the wetlands already are because of human beings.

When Chris and I are bailing the water out of my kayak in the shallows, the squishy muck of Lake Maurepas between my toes, he surprises me by saying, “It’s kind of a relief that it happened to you, just because you’ve had such a positive attitude all day.”

Richard chimes in to agree, telling me that my upbeat attitude has really boosted the group’s morale.

Simple observations from both of them, but I’m flabbergasted. I would describe myself in a lot of ways over these past few months, but having a positive attitude is not one of them. I’ve felt utterly tragic, utterly beaten down. I’ve felt like I looked for the silver linings everywhere and come up short, that I haven’t been looking hard enough. I haven’t laughed. I haven’t looked around and said, hey, I have a life that is beautiful and I’m doing what I love to do, no matter how stressed out I am.

Later I will laugh to myself about how there’s one more parallel between my disastrous semester and the disastrous situation southern Louisiana finds itself in. Much like the man-made levees and canals that caused this mess in the first place, the degree of emotional turmoil I’ve experienced is largely self-imposed. Not that my situation has not been, in itself, stressful, but I could’ve chosen to find solace in humor, in the joy simply to be alive and doing beautiful things with my life and having the fortune to be surrounded by wonderful, supportive peers and friends.

But I’m not quite there yet. Instead, I tell Chris and Richard that it means so much to hear them say that I’ve been positive (which probably doesn’t even make any sense). I try to play it cool, not looking either of them in the eye or telling them what’s going through my head, lest they realize how absurdly close to tears I am. At this moment, I’m just thrilled that the heavy, grave, self-pitying Jake that I’ve been in the last couple of months decided not to show himself on this kayaking trip. I’m glad to be free of him, if only for the afternoon. He’s exhausting.

The roll of thunder tells us we better make our way back; the storm that threatened to cancel our trip in the first place has decided to show up after all. As we make our way back into the narrow waterways, I glance to the right at the trees lining Lake Maurepas all the way to the horizon. In the distance, the faraway trees are swallowed in the hazy downpour, coming closer and closer to us. I say to Richard, “Look. Look! Isn’t it beautiful?”

When the rain hits us, all I can do is laugh. I tell Christine I don’t mind the downpour since I’m already wet from falling in the water.

She just shakes her head and laughs at me. “Definition of a trooper,” she says.

I have a hard time reconciling the lightness I feel now with the lecture we heard this morning. All this beauty, under water. Tons of people having to leave their homes. Little I can do besides write about it. Out here on the water, I think of nothing but paddling on and drinking in the beauty while I can. I squeeze ahead of the group the whole way back, powering through so that they’re far behind me. I want to have just a little moment to pretend it’s just me out here in the wild, nobody before or behind me. Eventually, the rain stops. I turn a bend out of earshot of the others and sing “Voice of the Bayou” into the open air.

I spot an egret on the banks to the left and approach it slowly, trying to get a closer look at it. It flies off ahead, toward where I’m going, and perches on a tree. I continue along. Though I’m no longer trying to get anywhere near the bird, it must think I’m chasing it now because every time I start to catch up to where it’s gone, it flies to a perch even closer to my destination. I slow down so that my classmates can catch up, but I still feel like I’m following the white bird all the way back to shore.

On the way home, a part of me waits for the come down from the bayou high. A part of me fears that the heavy, grave, self-pitying Jake will descend again upon me, that here on solid ground the responsibilities of the rest of my semester, the weight of my health issues and the illness of my relative, and all the issues that have weighed me down will dig into me, filling me with despair. But it doesn’t happen. I just feel exhausted and content. My worries creep into my consciousness, for sure, but now I think of sticking my paddle in the weeds and finally making it past the wetlands, albeit with excruciating slowness. I think of laughing at myself at every mishap. I think, it can’t be too far until open water.

Jacob Budenz is a writer and multi-disciplinary performer currently completing an MFA in Creative Writing at University of New Orleans. The author of PASTEL WITCHERIES (Seven Kitchens Press) and Spellwork for the Modern Pastel Witch (forthcoming by Birds Piled Loosely Press), Jacob has work most recently in Slipstream Press, Liminality, Glittership, and Mason Jar Press’s Broken Metropolis anthology.