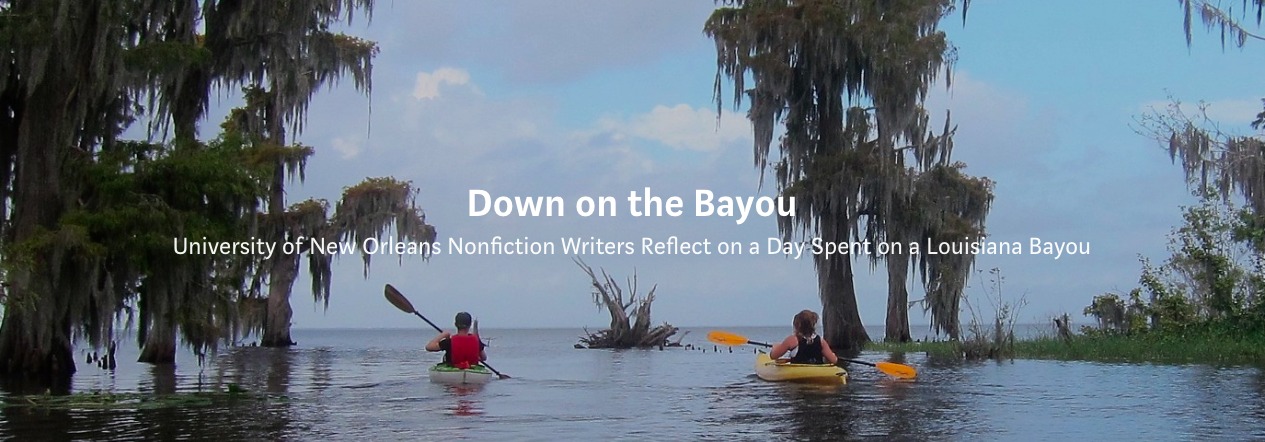

Students kayaking down the bayou for Richard Goodman’s MFA course. (Photo from: Down the Bayou website)

Editor’s Note: The following series “Transplant in New Orleans” is a week-long series curated by Piper Stevens as part of the Digital Research Internship Program in partnership with ViaNolaVie. The DRI Program is a Newcomb Institute technology initiative for undergraduate students combining technology skillsets, feminist leadership, and the digital humanities.

New Orleans is a city overflowing with vibrancy and culture, and it defines a piece of each of its inhabitants. ”Transplant in New Orleans” takes a tour of some of my favorite spots in New Orleans and shares some history and insight into what makes these places, and the city as a whole, feel like home to someone who has only lived here for a few years. In a time when everything feels a little quieter and more distant, I hope these articles remind us of all there is to love about living in the city that care forgot.

One of the first times I can say I truly appreciated the breathtaking nature surrounding New Orleans was on a kayaking trip in the bayou with my dad. The serine waters lined with lush nature is unique to this area and not to be taken for granted. Author Joe Kelly’s narrative of his trip kayaking down the bayou shines light on the beauty and precariousness of our bayous. This article was originally published on October 25, 2018.

Joe Kelley, writer and MFA graduate from University of New Orleans. (Photo: Joe Kelley)

I pulled up to the house at about 9:10 AM, ten minutes after the agreed upon meeting time. My shirt was flecked with spilled coffee, a result of jitterbugging over a series of chasmic potholes in order to avoid the foil of forever-construction on Jefferson Ave. My attire: ad hoc kayak-casual. My mood was somnambulant but enthusiastic. I was hungover but curious. Saturday morning was calm and breezy; the sun shined citrusy.

The house I’d arrived at was a typically cute, tidy Uptown bungalow. It was the only house on Octavia St. that had people milling about on the porch, so naturally I walked up. I grunted and smiled and greeted myself, in a manner of speaking, and was directed through the front door.

There was an empty living room. Through the empty living room was an understatedly decorated dining room full of chairs. The chairs were around a big table. Most everyone else had already arrived, various hues of perkiness and drowse. Sandals I’d never seen were being worn. I joined them, securely coffee-thermosed.

Seated at the head of the table, legs crossed knee on knee, was Bob Marshall. Marshall, I would come to understand, is a two time Pulitzer-awarded journalist. He was born and raised in New Orleans, largely accentless. His credentials include longtime service at the Times Picayune; it was during this tenure that his pieces about the people, places, and culture of South Louisiana earned him his accolades, Pulitzers included. Marshall is low key, friendly, wears his knowledgeability more like a delightful sunhat than a cap and tassel. Just behind him at the head of the dining room was a television plugged into a Macbook. Marshall began his presentation.

Slide after slide, graphic after depressing graphic. The situation, I came to learn, is dire; dire, but hopefully, in the best case scenario, somewhat reversible. The gist is this: the some four million acres of coastal wetlands making up Southern Louisiana are disappearing at an alarming rate and have been disappearing at an alarming rate for a long time now. The ecosystem that the indelible, mythologized Mississippi River — a waterway so fucking alive and critically arterial and continuously changing and inseparable from the logistics of industry that it seems to be the perfect natural encapsulation of the United States as a whole — developed over thousands of years has disappeared by something like 30% since the early twentieth century. Imagine a swath of land the size of a football field. Okay, now wait an hour. Okay, that’s gone now.

What most unsettled me, I suppose, sitting there in my ridiculous cut off jeans, is the sheer predictability of the cause of this tremendous loss.

I am from Wisconsin, and even I grew up knowing, at least vaguely, about the levees in Louisiana. The details, however, are striking. After a catastrophic flood in 1927 that killed roughly 500 people, leaving over half a million without a home and over 27,000 square miles under 30 feet of water, Congress passed an act that basically told the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to get down south and make that shit not happen again. Sensible. By the 30’s, the levees were built. Not long after that the problems started.

Basically, the levees made the area more inhabitable, and thus more viable for commerce and sprawl and population growth and all that other stuff we love, but they also started strangling the ecosystem. The rich alluvia of sediment — life stuff of the river that one could only describe as epochal, elemental — that the delta thrived off of, was built of, was now cut off and restricted. Cyclical dry spell sinking became a creeping constant. I sat there thinking of New Orleans sinking into the gulf. There was an imperceptible shift, down.

Then: Surprise! Oil! Holy shit! Around the time the levees were completed, perhaps incidentally discovered while being built, wellsprings of oil and natural gas were discovered along the Gulf coast. As humans do, we pretty much took that and ran with it. And ran with it. And ran with it.

Since the 30’s, some 50,000 oil wells have been raised, many of them offshore. But we gotta get this mess from A to B. Hmm. How’s, like, 15,000 miles of canals sound to everyone? Holy shit; another bullseye! They dug the canals, 15 feet deep, 150 feet wide, in a weblike grid all over the southern part of the state. The canals have pipes that pump oil everywhere; they also allow salt water to mix with the fresh water; this destroys local biodiversity.

In my chair in Bob Marshall’s dining room, slight headache, morning sun dribbling playfully through the broad windows, I was made to understand that this, too, is a massive problem.

Oh, and by the way, remember climate change? Yeah, so the sea levels are also rising. The NOAA estimates they could rise, like, four and a half feet by the end of the century. Land sinking; sea rising. I thought: invest in kayaks.

Marshall’s presentation ended on a more positive note, discussing a Master Plan that involves a hell of a lot of state money (Anybody have, like, 50 billion dollars I can hold for a minute? Don’t be a dick.) and a lot of consciousness and goodwill. Just let the river do its thing, is basically the idea. Here goes nothing.

***

Shortly after the presentation ended we all smiled and walked out the front door like everything was super chill and drove in a caravan about an hour west/northwest of the city to Shell Bank Bayou, a swampy terrain imbued in a thin strip of marshy land between Lake Pontchartrain and Lake Maurepas.

Shortly after stepping out of the cars and applying a hysterical amount of sunscreen and jaunty hats and life vests and dark sunglasses, we stepped into kayaks along the side of the highway and shoved off. Shortly after we paddled beneath an I-55 overpass and out into the bayou we were in the open water of the swamp, in the mouth of the delta, in a thin network of bayous hugged on either side by the firm tupelo and seemingly ancient softwood cypress trees, the wispy tufts of Spanish moss, the calls of silly birds.

Shortly after discovering miniature frogs, purple and white wildflowers, nonnative plant life and dark, obsidian beetles, we paddled up a narrow strait and our guide, John, pointed up: an eagle’s nest the size of a love seat; the eagle was absent, but the fact that it built it’s home there was something of a comfort. Shortly after winding lazily around the the thick, muddy, impenetrable and mysterious swamp, we wound back under the I-55 overpass, cars whooshing by, likely decorated with truck nuts, bellies full of refined petroleum, and back to highway’s side.

Shortly after celebratory beers we packed into convenient cars of our own and drove off down the highway to tuck into po boys at a charming place called the Crab Trap that I swear is literally shaped like a crab trap. We talked about what we saw; we didn’t talk about what we saw.

Shortly after that we piled in cars and drove home. Shortly after that, on the way into and around New Orleans, all over this one of a kind coastal region, over the rare and beautiful and mystifying landscape, over this temporarily inhabitable Earth, I felt some new understanding of things vanishing, of things impermanent. I felt strange and small.

And shortly after that, things felt clear.

Original Editor’s Note: Joe Kelly took part in Richard Goodman’s Master of Fine Arts nonfiction writing workshop at the University of New Orleans, where the students take a kayak trip down a southeastern Louisiana bayou in order to observe the issues and conditions that make the bayous beautiful and precarious. Once they finish their full-day kayaking adventure, the students reflect and write, creating pieces that encapsulate their experience and give new awareness about the bayous. ViaNolaVie will be running these pieces as a continued series every week, and you can also read more student writing here and here. And now for Joe Kelly’s “What We Talk About When We Talk About Kayaks.”

Joe Kelly was born in Illinois and grew up in Wisconsin. He obtained an MFA in Creative Writing from the University of New Orleans. He currently lives, works and writes in Milwaukee.

NOLAbeings

Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings

Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

Data corner: Adobe Suite (create a PDF, social media graphic, presentation, edit a photo and video

Data corner is where you go to work with analytics and top tech skills. It takes on everything from PERL and SQL to Canva and Sprout Social.

Data corner: Adobe Suite (create a PDF, social media graphic, presentation, edit a photo and video

Data corner is where you go to work with analytics and top tech skills. It takes on everything from PERL and SQL to Canva and Sprout Social.