By: Hope Knoebel, Caroline Mendes, Charlotte Petruccelli, and Maia Marcoschamer

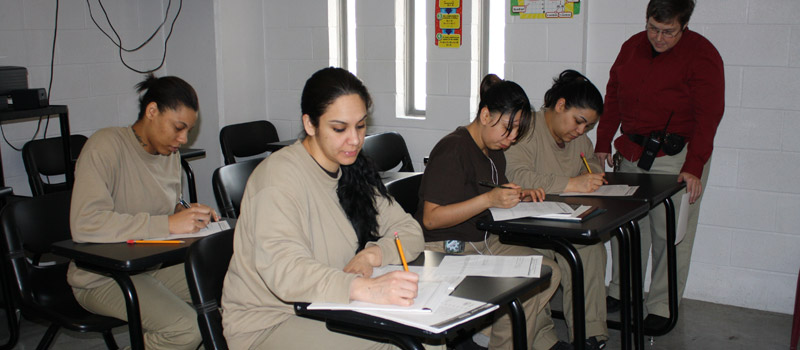

With 48% of incarcerated individuals not having a highschool diploma, it’s difficult for prisoners to expand their education as is. Provided on the official Louisiana Department of Public Safety and Corrections website, it is claimed “ Correctional education programs help break the cycle of criminal behavior by providing the knowledge and skills necessary to succeed while incarcerated and post-release.” (LA DPS&C 1). Yet, studies show that this doesn’t show to be true at all times. For instance, many formerly incarcerated prisoners got together and wrote their experiences under a Quora topic; they claim that while the education may not be inadequate itself, but commitment of both the students and professors is. One formal inmate even claimed that during his time, he took a 6-month-long course on just writing a check; a skill that he already knew and didn’t need to further study during her incarnation. Additiona lly, many prisons end up distributing their education based solely off of good behavior, not allowing other inmates to better themselves which ultimately and commonly leads to high prison re-entry rates (Justice Center 10). While some of these singular experiences do not summarize prison education as a whole, it showcases the impracticality of the current system.

lly, many prisons end up distributing their education based solely off of good behavior, not allowing other inmates to better themselves which ultimately and commonly leads to high prison re-entry rates (Justice Center 10). While some of these singular experiences do not summarize prison education as a whole, it showcases the impracticality of the current system.

Many, when thinking about the education problem in prisons, focus on the actual credits and classes that are options for prisoners like welding, cooking and auto repairs. But not only are these classes somewhat random, they provide no actual curriculum and other inmates end up teaching the courses. “Is that really preparing for a crime-free life outside in the real world?” Molly Gill, FAMM director of Federal Legislative Affairs, said. The average US prison sentence is almost 13 years and many don’t understand that this means people miss 13 years of modernization of their society. A formally incarcerated woman named Ivy Mathis, who works at VOTE a non profit to help women coming out of prison tells a touching story. Ivy met a woman who was coming out of a 32 year sentence. She entered in 1982, when there was no Iphone, different roads and buildings. She had to then work up enough money and educate herself on the way the world has moved on without her. If the prison system is ready to charge immense sentences they should be prepared to educate the prisoners on real world skills. If they are educated on the new ways of the world and helpful skills that will put them ahead when they get out, the reentry rate will significantly decrease, but obviously this corrupt system does not care about reentry rates or rehabilitation.

Back in July of 2022, about 25 incarcerated youths were relocated to Louisiana State Penitentiary, also known as Angola, the largest maximum-security prison in the United States. The problem with this is that, “advocates warn that youth housed at Angola may be deprived of their education and lack other opportunities for growth and rehabilitation,” as reported by the Southern Poverty Law Center. Angola is simply not equipped to provide adequate schooling for these children. Patrick Cooper, a teacher hired at the Angola youth-detention facility, corroborates by testifying that, “he wasn’t given a roster of students. He didn’t even know what grades or courses the kids were supposed to be in. He also had no access to individualized educational plans for special-education students, despite legal requirements well-known to Cooper, a past director of special education for the state of Louisiana.” Louisiana state law requires 360 minutes of instructional time per day, totaling 177 classroom days per year— a standard unattainable considering Angola’s conditions. The children spent more time in their cells than in the damaged, neglected classrooms. The question posed to the officials who allowed this mistreatment were, how could we expect these children to rehabilitate when they lack basic education?

Amongst other issues, one important corrupt factor of the prison education system at Angola is “when serving a life sentence, only one credit is available ” – stated by Ivy Mathis. The reason for this is essentially due to the notion of not finding a purpose of helping someone who is already sentenced for life. However, this is detrimental to the prisoners mental health and well being. When only receiving one class throughout the entirety of the life sentence, what happens is thoughts of suicide due to not finding a purpose in even staying alive in prison. In Angola, 80-90 percent incarcerated are currently serving a life sentence. With that, there had a 50% increase in death rates at Lousiana prisons with 6% being suicidal from years 2019-2022. Another injustice faced in the education department at Angola prison is that the teachers and administrators don’t even know what grade, level, or course the students are supposed to be taking so pretty much everyone learns the same material which is ridiculously simple regardless of age, IQ level, or prior knowledge. Overall, although Angola tries to incorporate some education in the inmates daily life, the prison fails to give any real help to inmates with getting a decent education. In examining Angola Prison, it becomes clear that it is not just a place of incarceration, but a place of exploitation and injustices.

This piece is part of an on-going series from professor Betsy Weiss’s class, “Punishment and Redemption in the Prison Industrial Complex,” which is taught at Tulane University in the Young Public Scholars Pre-College Program.

NOLAbeings

Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings

Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

Data corner: Adobe Suite (create a PDF, social media graphic, presentation, edit a photo and video

Data corner is where you go to work with analytics and top tech skills. It takes on everything from PERL and SQL to Canva and Sprout Social.

Data corner: Adobe Suite (create a PDF, social media graphic, presentation, edit a photo and video

Data corner is where you go to work with analytics and top tech skills. It takes on everything from PERL and SQL to Canva and Sprout Social.