Deconstructing the Quadroon Ball (Photo by The Race Card)

Louisiana has always been a breeding ground for complicated and tangled interracial relations, and interracial relationships went beyond “complicated.” Americans from different states did not even acknowledge or endorse this distinctive culture of relative racial leniency that had developed, and many worked to dismantle it by enforcing strict racial boundaries in which relationships between whites and Blacks were prohibited. Although Louisiana is “the state in the US with the highest number of white people with African DNA,” it is simultaneously home to the second and third most racially segregated cities in the South, Baton Rouge and New Orleans, respectively (Yee, 2015).

Race directly impacts families in that it once ascribed who could be considered a family and continues to determine the social and economic location of families. New Orleans is home to a complicated history regarding interracial marriage and interracial extramarital affairs. By examining articles written in The Times Picayune articles from 1841 to delineate attitudes towards family, specifically those regarding marriage and extramarital affairs, it is argued that these viewpoints were progressive for the time. It is also argued that these viewpoints legitimize the existence of quadroon balls. Lastly, it is demonstrated that the quadroon balls are related to family structure and familial attitudes of New Orleanians around 1841.

The Times Picayune article from 1841 is evidence of negative sentiments regarding marriage and commitment. The paper sheds light on the difficulties of marriage, how it may become unfulfilling and sanctions extramarital affairs. The paper writes of Tom Slinger as “the man who dreaded his wife’s tongue.” When the watchman asks Tom if he is married, Tom muses that this question “insults” his feelings because “there is too much of a painfully distressing reality in it,” (Picayune, 1841). Tom says things such as, “don’t take me home to my wife,” which underscores that he is unhappy in his marriage. His unwillingness to go home to his wife implies he is fearful of what will happen when he returns home. He asks the watchman for advice, and the watchman responds that unless Tom fears his wife will do him bodily harm, he will have to “bear” her tongue. This relates to the struggles that become apparent from an inter-racial marriage at this time.

The harsh realities of marriage often lead to the notion of “swapping wives.” The article utilizes the case of “swapping wives” in New Hampshire to censure extramarital affairs. The “swapping wives” section describes the case of two men who married sisters and then exchanged their wives for one another. When one wife runs away with another lover, The Picayune asserts it was her turn to “assert her exercise of the glorious right of free trade and quit her bed and board.” The Picayune concludes that they are “positively surprised and shocked at such carryings…they didn’t use to do such things in New Hampshire when we lived there,” (Picayune, 1841). The description of such affairs as “glorious” and “positive” evidence is a sanctioning of such and, perhaps, even an approval of these affairs. This is a very progressive stance for the time, especially because a woman’s seeking of another lover is approved of; however, this attitude follows when contextualized with the existence of the plaçage and “quadroon balls”.

Intimate relationships between white men and women of color in antebellum New Orleans were denoted commonly by the term “plaçage,” and were romanticized in New Orleans history. This is shown through depictions in artwork, films, and articles from this period. Plaçage was recognized by the French and Spanish slave colonies in New Orleans as a system through which white men could enter into civil unions with non-Europeans of Africa, Native American, and mixed-race descent. However, once the French and Spanish relinquished their control over Louisiana and the state became “American,” legal prohibition against interracial marriage was enacted in “an attempt to stigmatize free women of color who made families with white men,” (Melle, 2013).

The lore follows that the Inhabitants of New Orleans were unusually open about interracial relationships due to the French and Spanish cultural influence, and nothing epitomized this more than the city’s famed “quadroon balls” (Aslakson, 709).

The notion that New Orleanians at the time uniquely sanctioned interracial relationships is utterly unsubstantiated considering what took place at the quadroon balls.

The myth regarding quadroon balls holds that they were “dances open to young free women of mixed ancestry and white gentleman of means,” (Aslakson, 709). Writers romanticized and glorified these balls and their attendants, specifically “the charms, graces, and elegance of the quadroons in addition to their physical beauty,” (Aslakson, 712). However, what actually occurred at these balls was far from “elegant” or “charming.”

The commonly accepted myth is that these balls allowed women of color to form a plaçage relationship with a white man. During French and Spanish colonization, plaçage relationships involved legally binding contractual agreements in which the mistress was set up with a house, an income, and any children born in this arrangement were provided for by their father. America had out-lawed interracial marriage by the time these balls took place, rendering it exceedingly difficult for children of color to inherit from their colonial father, making this story hard to believe.

An article in Afropunk by The Race Card deconstructs the quadroon ball, concluding that quadroon balls were not about cultivating mutually beneficial relationships between white men and quadroons. The article concludes: Continuing to retell the fanciful myths about the quadroon ball only serve to paper-over another heinous injustice of slavery—the use of slave women for sex and sex trade—with a convenient and white-male centric fantasy (The Race Card, 2016)

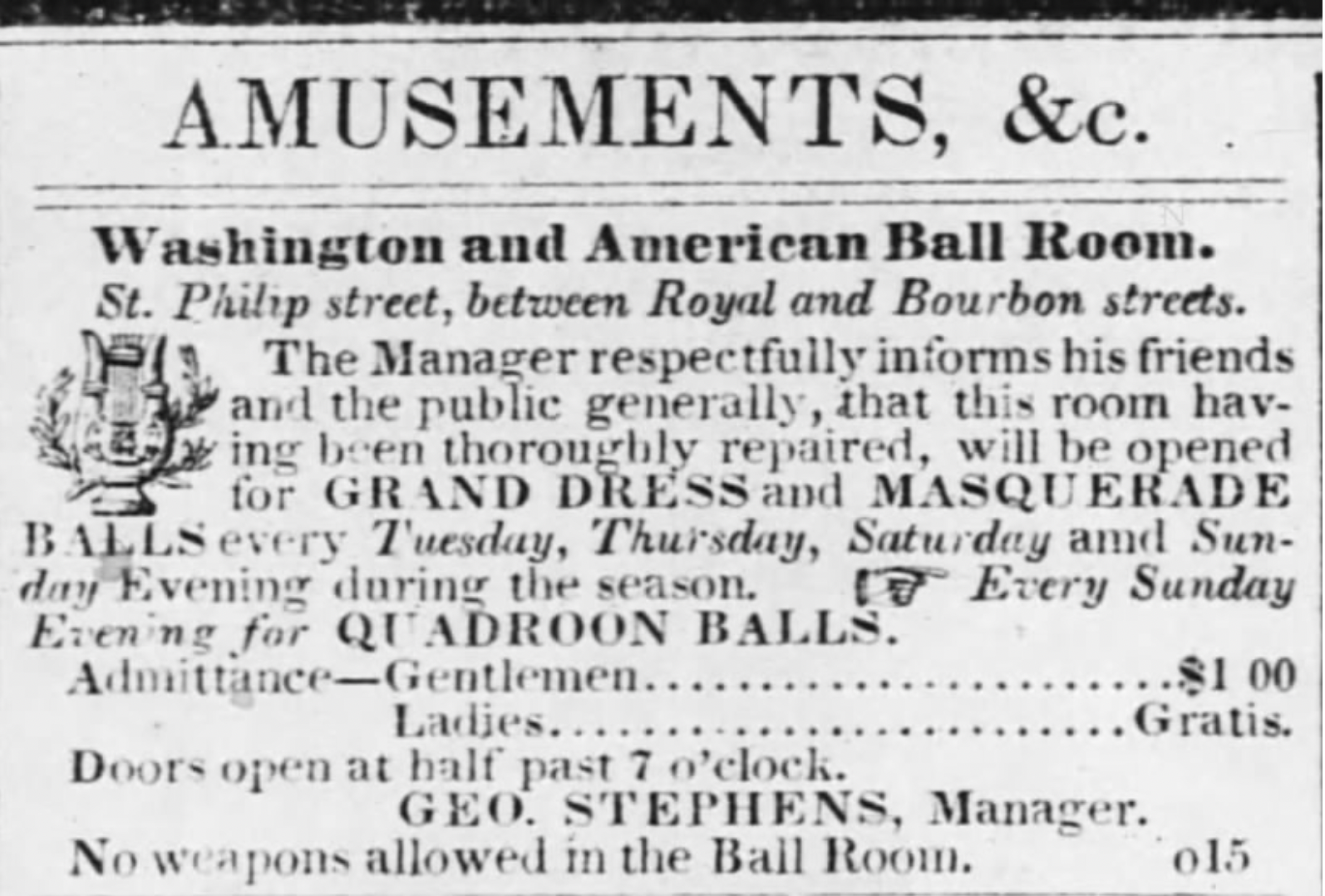

This article argues for and exposes the real nature of these balls: “a not so-veiled cover for prostitution,” (The Race Card, 2016). The Louisiana Supreme Court “heard cases that suggested slaveholders sold or leased out slave women for prostitution at these balls,” (The Race Card, 2016). This article evidences the seediness of the supposed “glamorous” and “lavish” event by pointing to indicators of such present in a quadroon advertisement. Signs in the advertisement that underscore the ball’s true purpose include the promise of a police force, the statement that the ball was to be hosted in a former gambling hall notorious for debauchery, and that the ball’s proprietor was to be Sam’l S. Smith, “a well-known scoundrel and interloper from the north,” (The Race Card, 2016). Ultimately, these balls served to quench and cater to the perverse sexual desires that involved the sexualization of Black women by white men at the time.

Taking these realities into account, it is easy to refute the claim that inhabitants of New Orleans were “unusually open about interracial relationships” for Americans at the time due to the influence of their Spanish and French predecessors. The existence of these balls underscores the sexualization and objectification of the Black female body by white men as an item for sexual consumption; these were prostitution rings, not lavish balls, to initiate a gracious agreement. The sexualization of Black women does not indicate any increased tolerance of races other than white. Slaveholders had been raping their female slaves for centuries, which does not render them more tolerant. In fact, it renders them even more monstrous—as beings perceiving Black women as bodies of flesh, but not as bodies with any sort of humanity attached to them.

However, the myth of the plaçage did legitimize these balls. This myth served as an alternate and more socially acceptable explanation for what was occurring at these quadroons. Dr. Emily Clark, a historian interviewed in a Huffington Post article about the myth of quadroons, asserts: If you asked a white nineteenth-century American what a quadroon was, they would answer that she was a light-skinned free woman of color who preferred being the mistress of a white man to marriage with a man who shared her racial ancestry (qdt. in Melle, 2013).

It also follows logically that the newspaper sanctions extramarital affairs in light of the happenings of these quadroon balls. Because the newspaper’s audience mainly consisted of white men, it makes sense that it would try to legitimatize the very balls they advertise and the sexual relations that occur because of them. Firstly, the paper’s authorization of these affairs may serve to inform these women of what is socially acceptable. Secondly, the inclusion of the attitudes and ideas could have been utilized as a social tool to pacify these women by providing them with a reliable form of media both sanctioning extramarital affairs and evidencing unhappy marriages. Ultimately, both the myth of the plaçage and the newspaper’s asserted attitudes and conventions align with the existence of quadroon balls.

The myth of the quadroon balls affected the family structure of New Orleanians at the time in a few ways. Firstly, the balls produced illegitimate children and created more complex family dynamics. Although these illegitimate children and their mothers were not recognized as part of the nuclear white family unit, they extended the family bloodline and produced offspring to be contended with, nevertheless. Secondly, the balls evidenced an extremely limited tolerance for legitimate interracial affairs, evidenced by the fact these events were merely veiled prostitution rings—not lavish happenings designed to produce plaçage arrangements, as legend has it. Thirdly, they affected cultural and social attitudes towards extramarital affairs, evidenced by The Times Picayune’s sanctioning and promotion of these balls.

Times-Picayune advertisement for a Quadroon ball from 1844 (From Ancestry)

Ultimately, racial relations, attitudes, and interracial marriage have always been complicated, intricate affairs in New Orleans and America as a whole, both stained by the existence of slavery and Jim Crow laws. New Orleans, specifically in 1841, sheds an interesting light upon interracial affairs, particularly extramarital ones. The myth of the plaçage and quadroon balls in New Orleans, or at least the common misconception regarding what occurred there, may surprise some Americans, considering the existence and perpetuation of slavery at the time. However, deconstructing these myths reveals a more telling and likely story—one of prostitution and the commodification of the Black female body. The quadroon balls—legitimatized prostitution rings—align with attitudes expressed in The Times Picayune regarding family and extramarital affairs. The newspaper serves to further legitimize and cement the existence of these atrocious events.

180 years have passed since the publication of the 1841 edition of The Times Picayune. Quadroon balls no longer exist and neither do laws prohibiting interracial marriage. However, the realities that constitute them are still commonly misconstrued, while the event itself is still mystified and glamorized to the present day. This evidences a larger problem: the erasure of Black stories to produce a telling of events that will conform to the American white male-centric narrative. Further efforts should be taken to popularize the deconstruction of the quadroon and the plaçage. This should not be done to reveal the historical structuring of New Orleanian familial organization or attitudes, but rather be precipitated to tell unheard, suppressed Black stories and spread the truth regarding America’s painful past. It is important to focus our attention on how these balls intensified the sexual desires of white men toward Black women.

This piece was edited by Anna Blavatnik as part of Professor Kelley Crawford’s Digital Civic Engagement course at Tulane University.

Bibliography

Melle, Stacy Parker Le. “Quadroons for Beginners: Discussing the Suppressed and Sexualized History of Free Women of Color with Author Emily Clark.” HuffPost, HuffPost, 4 Nov. 2013,

https://www.huffpost.com/entry/quadroons-for-beginners-d_b_3869605

Aslakson, K. “The ‘Quadroon-Placage’ Myth of Antebellum New Orleans: Anglo-American (Mis)Interpretations of a French-Caribbean Phenomenon.” Journal of Social History, vol. 45, no. 3, 2011, pp. 709–734., doi:10.1093/jsh/shr059.

The Race Car. “Know Your Black History: Deconstructing the Quadroon Ball.” AFROPUNK, 27 Oct. 2016, afropunk.com/2016/10/know-your-black-history-deconstructing-the-quadroon-ball/.

NOLAbeings

Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings

Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

Data corner: Adobe Suite (create a PDF, social media graphic, presentation, edit a photo and video

Data corner is where you go to work with analytics and top tech skills. It takes on everything from PERL and SQL to Canva and Sprout Social.

Data corner: Adobe Suite (create a PDF, social media graphic, presentation, edit a photo and video

Data corner is where you go to work with analytics and top tech skills. It takes on everything from PERL and SQL to Canva and Sprout Social.