“What they call rock and roll now is rhythm and blues: I’ve been playing for 15 years in New Orleans.” – Fats Domino, 1978.

Fats Domino singing “Blueberry Hill” on the “Alan Freed Show” 1956 (Creative Commons).

In 1985, Back to the Future featured a climactic scene in which Chuck Berry’s iconic sound is retroactively inspired by a white, Van Halen obsessed teenager. His fictional cousin, Marvin Berry, calls him up mid-performance declaring, “Chuck! You know that new sound you’ve been looking for? Well listen to this!” The next shot pans to Marty on stage singing Berry’s “Johnny B. Goode” and imitating his signature guitar move The Duck Walk. Back to the Future directly implied to its viewers that Marty McFly “invented” rock and roll, a genre undoubtedly linked to Black musicianship. While the film is a work of fiction, the notion of whitewashing of Black music is very real.

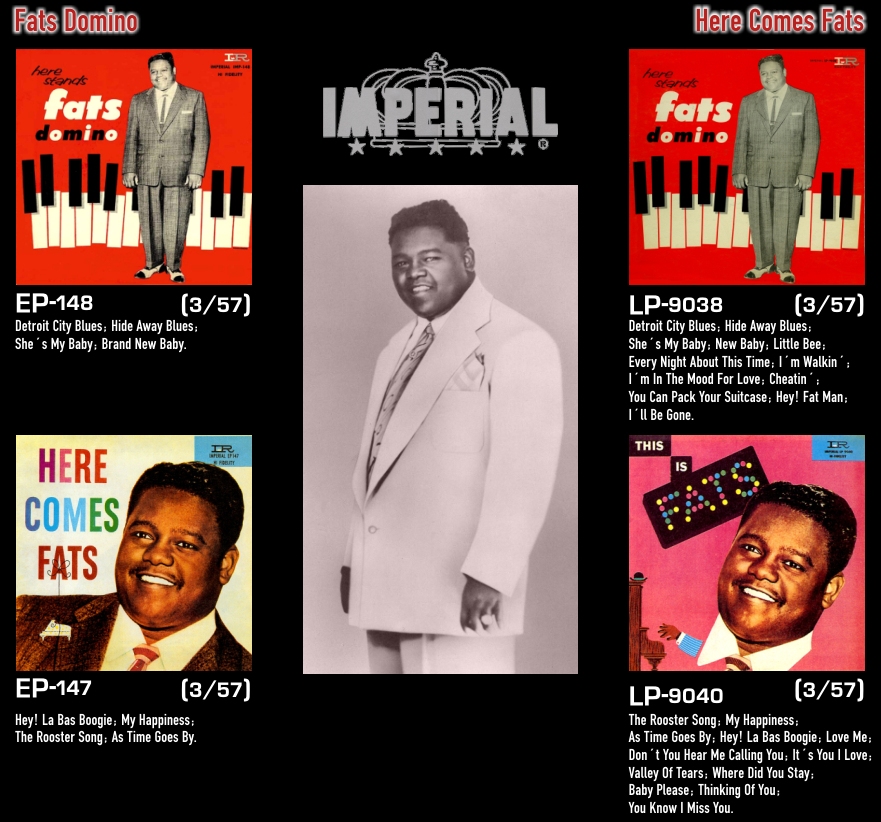

Fats Domino record covers

New Orleans native Antoine “Fats” Domino’s first major hit “Ain’t That a Shame” made the top 10 in the summer of 1955 followed by a string of big selling records including “Blueberry Hill” (1956), “Blue Monday” (1957), “I’m Walkin” (1957) and “Walking To New Orleans” (1960). During the first wave of rock and roll, Domino sold 65 million records—more than any other musician with the exception of Elvis Presley. Presley himself frequently paid tribute to Fats’ contributions in the genre, “At one point, after a performance in Las Vegas in which an interviewer referred to Presley as ‘King’, Elvis pointed towards Domino, who was sitting nearby, and said, ‘There’s the real king of rock ’n’ roll.’” So why is Domino still so uncredited for the birth of rock ‘n’ roll?

Segregation of restrooms

Although Fats attained what is considered “mainstream” success, he was still a Black man living in a white man’s world. Most notably, in May of 1956 Domino was headlining a show in Virginia where, in keeping with the segregation laws of the time, the whites and Blacks were allocated different seats. The Black fans occupied the main floor whereas the whites occupied a balcony above, often with limited capacity. Many young white fans escaped to the far less dense main floor where they were actually shown dancing and enjoying the show with Black fans alike. The clear disobedience of southern segregation proved to be too much for those on the balcony, who threw bottles from above in response to the mingling. After the show ended, an angry white mob even tailed Domino and his fellow Black performers back to their hotel. Like many other white southerners, they had the feeling that Domino’s music represented a serious threat to the racial apartheid of the Jim Crow South.

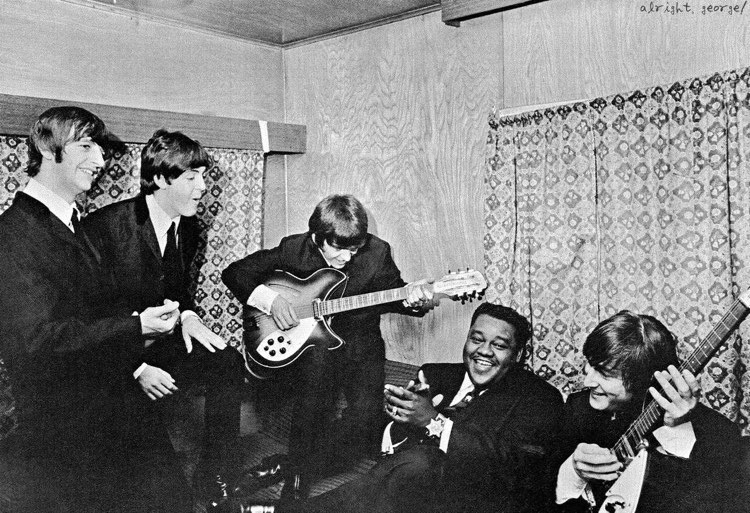

In addition to the racism Domino experienced throughout the peak of his career, by the 1960’s his chart-topping singles had begun to taper off. The rise of The British Invasion and their earth-shattering popularity paved a way in rock music for white musicians to succeed and left the Black pioneers in the dust. According to Stones guitarist Keith Richards, Muddy Waters had apparently been hired to paint, rather than play in recording studios, before The Rolling Stones reenergized the blues genre and found a new audience for it in the mid-60s. Many are quick to condemn the bands for stealing the blues, but these artists consistently strive to bring recognition to their inspirations. In one famous event in 1965, the Stones refused to play on the American show “Shindig!” unless they could be supported by Howlin’ Wolf—another trailblazer in rock music.

The Beatles and Fats Domino in New Orleans. (Creative Commons)

It appears the fans are truly at fault in creating this current whitewashed mindset of rock and roll. This notion was affirmed in 1968 when Domino charted with only one single, a song that was, ironically, inspired by his own musical style. In 1994, Paul McCartney remembered how he came to write a Beatles No. 1, “’Lady Madonna’ was me, sitting down at the piano trying to write a bluesy boogie-woogie thing… It reminded me of Fats Domino for some reason, so I started singing a Fats Domino impression. It took my other voice to a very odd place.” The song went to the top of the UK singles chart in March of 1968 and peaked at No.4 in the US. On September 7th, 1968, a cover version by Domino himself peaked at No.100 on the Billboard Hot 100 and was his last single to ever make the pop charts. Seeing this reality through the charts makes it hard to shake the notion that Domino is still treated as a footnote in rock and roll history.

Domino’s former home in the Lower 9th Ward. (Creative Commons)

In the mid 2000’s, filmmaker Joe Lauro set out to investigate this gap and bring recognition to the musical legend by producing a documentary on Domino. For years, the producer visited the singer and they would talk, listen to music and play pool. Lauro describes entering the “parallel universe” of Domino’s double-shotgun house in the 9th Ward neighborhood of New Orleans where he grew up. Domino’s first response when they met was, “I don’t want to be documented by nobody!” Everyone who knew Domino reports that he was incredibly camera shy. The men would often wager pool, and Domino only agreed to sign a deal for the film after finally losing a game five years later.

Domino put New Orleans on the map, and now many people living in New Orleans today have no idea who he even is. He has been taken for granted by rock and roll fans due to his humility and it’s far too often used as a justification on why his legacy has been overlooked. Nevertheless, the whitewashing of rock music is truly responsible. The artists inspired by Domino consistently display their acclaim for the singer, but we as fans owe it to his brilliance and breakthrough musical contributions to celebrate him as the star that he was. Too many people don’t recognize his power and influence on rock music— ain’t that a shame?

NOLAbeings

Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings

Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

Data corner: Adobe Suite (create a PDF, social media graphic, presentation, edit a photo and video

Data corner is where you go to work with analytics and top tech skills. It takes on everything from PERL and SQL to Canva and Sprout Social.

Data corner: Adobe Suite (create a PDF, social media graphic, presentation, edit a photo and video

Data corner is where you go to work with analytics and top tech skills. It takes on everything from PERL and SQL to Canva and Sprout Social.