Editors Note: The following series “Beyond the Beignets: A deeper look at New Orleans” is a week-long series curated by Rena Repenning as part of the Digital Research Internship Program in partnership with ViaNolaVie. The DRI Program is a Newcomb Institute technology initiative for undergraduate students combining technology skillsets, feminist leadership, and the digital humanities.

Because I live in New Orleans as a Tulane student, I often feel like a visitor instead of a resident because Tulane’s social life is disconnected from the city’s year-round residents. When creating Beyond the Beignets, I compiled 10 articles that articulated an often overlooked part of city life. In order to establish a connection within New Orleans residents, The Arts Council New Orleans has created five large murals within walking distance of each other downtown. By drawing well-known artists and student interns alike, the Arts Council has succeeded in adding to arts and culture in an urban landscape. Listen or read on to hear about how “Creative Placemaking” has the power to change New Orleans. This article was originally published on August 22nd, 2019.

New Orleans is getting a lot more colorful lately. Local and national artists are turning blank brick and concrete walls into massive outdoor artworks, including five new murals that were recently unveiled on downtown buildings. Recently we sat down with Heidi Schmalbach, Executive Director of The Arts Council New Orleans, to talk about new movements in public art and how it can transform the local community.

Unframed: Brandan B-Mike Odums’ work in partnership with Youth Artist Movement, at 636 Baronne. (Photo: http://thehelisfoundation.org)

Unframed is the name of this new mural project downtown. Tell us about it.

Unframed is a project that the Arts Council conceptualized and then partnered with the Helis Foundation to fund. The concept was to concentrate a portfolio of five large-scale murals in a walk-able area in downtown. I think we see murals all over the city, fewer in the downtown core. We really wanted to focus on creating this walk-able area where people could see a variety of artistic interpretations in a contained geography.

Tell us about the artists.

When we designed this project, we knew that we wanted to include a combination of local talent and also invite national and international artists to be part of this exhibition. We did an open-call process locally, and we received close to a hundred applicants. We have one community mural, which was created by Brandon Odums — B Mike — working with 14 young people and a paid internship from the Young Artists Movement. Of the remaining four, at least two of those would go to local artists, and we were just lucky enough that the local talent pool is so great that we ended up with three out of those four [being local]. We have Carl Joe Williams. Team A/C, which is a combination of two artists, Carrie Norman and Adam Modesitt; they both are architectural designers, and they’re instructors at Tulane. MOMO, who has an international profile, but actually keeps a studio here in New Orleans. And the final mural was created by a Polish team called Etam Cru.

What kind of subject matter are you looking for?

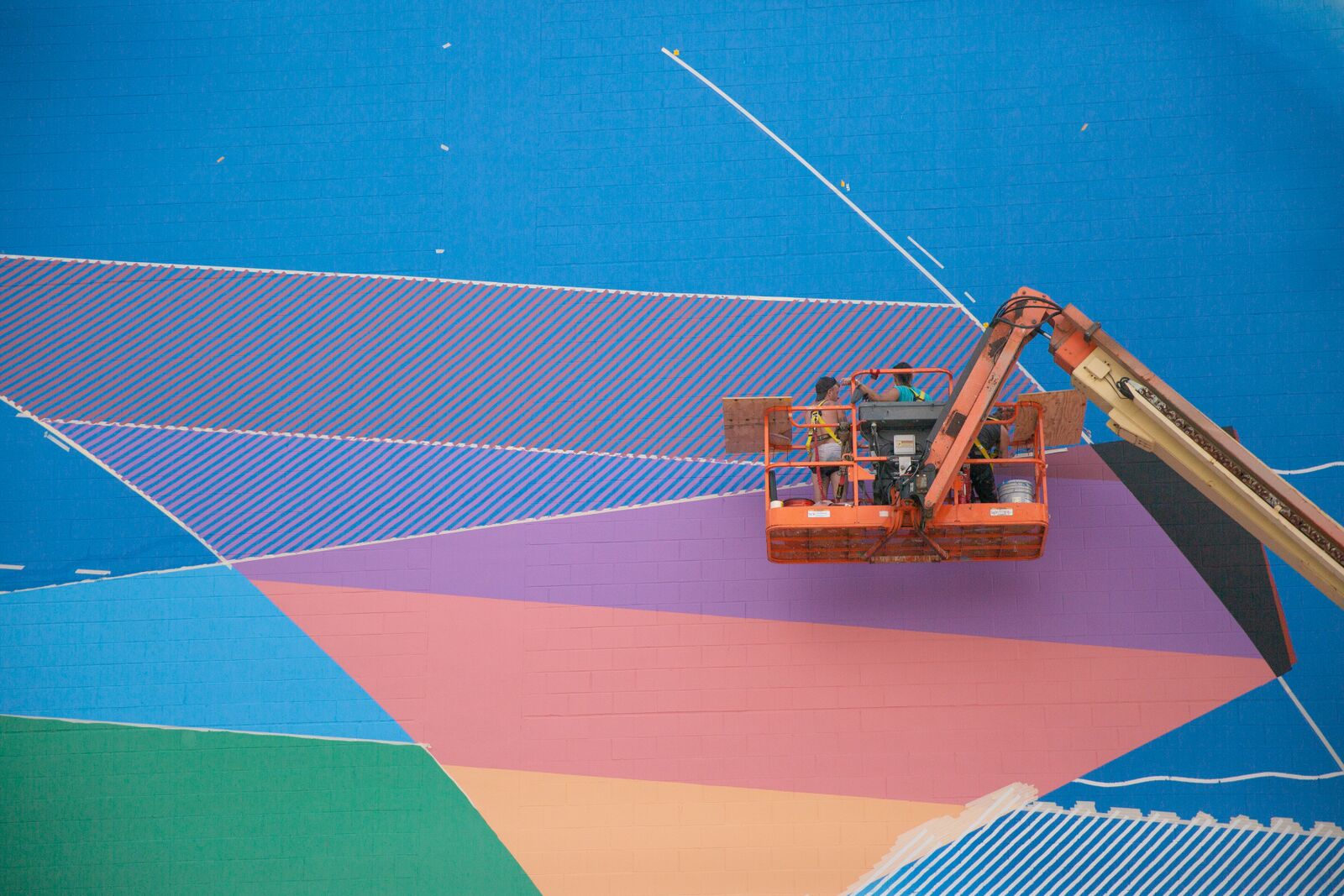

We don’t want to put limits on the artistic vision. We wanted, and I think this is what we got, a combination of narratives. Also things that are more process-based and also just stunning in their scale and make you say, ‘how did they cover that much space?’ Especially, I think, in MOMO’s mural; it’s just huge. And it looks beautiful in pictures, but really seeing it in person, you’re kind of awed by just the scale. And how did he create that kind of a gradient at such a large scale? We didn’t want to dictate what the subject matter would be. We really let that emerge from the artists.

Unframed: MOMO’s mural in progress at the Ogden Museum of Southern Art (Photo: http://thehelisfoundation.org)

Murals have been around for quite a while, but has technology changed the way that we are able to implement murals with digital technology?

Definitely. In a couple of different ways. Certainly, to go larger and to use the power of projection, to be able to create a template. And that’s been around for a while, but it’s definitely just adding to our capacities as public art administrators and for artists to go larger. And just thinking about outdoor artwork more generally, it really opens up the possibility. In a city like New Orleans, where we have a lot of restrictions on painting on walls for good reason, most of the city falls into some level of jurisdiction of historic districts. So, there’re limitations on what we can do that is semi-permanent to permanent. But the possibility of light and projection opens up. We are able to create these incredible digital projections that read like murals and to change it up every year.

I think mural making is already a pretty democratic process. Lots of people. That’s what I love about it. Many people can be involved in the creation of a mural working with an artist, whether it’s contributing concepts or words that are inspirational or physically helping the artist paint the mural. And I think that we have that opportunity even more so when we’re working in the digital realm. We’ve worked with the Young Artist Movement last year and will again this year . Last year, they worked with Carl Joe Williams to create a piece that premiered on Gallier Hall. That was in front of crowds of 60,000. Being able to see, especially for young people, your work on display in that manner is truly transformative. You can see it in their faces. You can see it in the audience’s faces.

Unframed Mural by Etam Cru from Poland at 600 O’Keefe Street (Photo: http://thehelisfoundation.org)

In what way are murals transformative?

Like all forms of public art, murals have a potential range of benefits, from the very intrinsic to the instrumental. For a community, murals should be reflective of community identity and reinforcing community values — sometimes, raising difficult questions and causing people to stop and look and potentially have a conversation with the person next to them about what they’re seeing. There’s a really powerful potential in all public art making, but murals especially. There’s a really fantastic example of this in Philadelphia.

Mural Arts Philadelphia is one of the best mural programs, probably in the world. And recently they started a program called the Porch Light Program. They partnered with the Philly Health Department to create murals that are specifically focused on individual and community-level healing. They worked with the Yale School of Medicine to do an impact study on the first few years of this program, and they were able to empirically demonstrate that people living within a 1-mile radius of these murals reported increases in collective efficacy, social cohesion and a decrease at the individual level on stigma towards people living with mental health issues and addiction.

And I think we have evidence in the same way that that the integration of arts into education has educational benefits. Data shows that over and over and over again. It’s more challenging to show community-level benefits, for sure. But we have the same kinds of evidence that show that accessible arts programming or participation in the arts improves people’s lives. We know that this is true, and I think that’s one of the most promising things about public art, in general, is that possibility.

I’ve been reading a lot about creative placemaking, which is kind of a new buzzword about changing our environment by bringing arts and culture into the urban landscape. Is that a trend that you’re seeing?

One hundred percent. It is a trend and I think it’s, on balance, a positive trend. Creative placemaking is an umbrella term that refers to a variety of practices that seek to intentionally center arts and culture, when we’re talking about all different kinds of community development or revitalization efforts. So, done well, I think creative placemaking is an asset-based approach that works from what a community already has going for it, particularly its arts and culture assets, and builds from there.

It’s a relatively new term. Community arts practice has been around for a really long time. But in 2009, the chairman of the NEA at the time, Rocco Landesman, was looking for a way to essentially shift the narrative about the arts, and what arts and culture bring to the table, by shifting it from ‘we need funding because otherwise, we won’t be able to run organizations’ to ‘look at all of the things that arts and culture bring to the table.’ And I think you can see it summarized in the rhetorical shift of the NEA’s tagline. It used to be, ‘a great nation deserves great art.’ And then, it changed around 2010 to, ‘art works.’

There is also a counter-narrative that is being developed by a writer and thinker named Roberto Bedoya. He critiques creative placemaking for good reason — for it being too narrowly focused on purely economic outcomes. So, for example, if your measure of success is increased property values, we have an issue. He focuses on the objective of cultivating or reinforcing a sense of belonging through creative placemaking — whether that’s newcomers, like new immigrant populations to a community, really declaring through their arts and cultural practice, I belong here, or it’s working to highlight work that’s already going on. He calls it place-keeping. And I think that is rhetorically important when you think of, okay, placemaking.

MOMO mural completed (Photo: http://thehelisfoundation.org)

I’ve also read that art is moving from static to experiential. Your annual LUNA Fest does this – it’s participatory in a way that other things are not.

Absolutely. I think that there should be room for all levels of temporality when it comes to public art. Permanent pieces are still really important. But there’s also more and more recognition that performance-based art is public art. And temporary interventions can be just as powerful as a sculpture that is meant to last for 50 years. I think the more that we’re able to broaden our thinking about that and also, on the flip side, to be able to resource all of the forms, especially in the context of New Orleans. It’s such a creative and performative city that we should be able to resource those creators in the same way that we’re able to resource artists who create permanent pieces. So, making space for all of it and making sure that we’re resourcing it is certainly one of our goals.

How does New Orleans stack up with the rest of our country in public art?

That is a tough question for the person who’s tasked with running the public art program. I have a two-part answer. I’ve lived a lot of different places and New Orleans is without a doubt the most creative city that I’ve ever been in. I think that everyone is creative, but the number of people, the concentration and the density of people who are in touch with that creativity in the city is just mind-blowing.

I think it’s a common description that in New Orleans, culture and creativity bubble up from the sidewalk, which is true. But that can obscure the fact that there are people behind that creativity and that culture who need to be fed and nurtured and paid and supported. And so I guess that’s my counter to, ‘how are we doing?’

The second part of the answer is, I think that because we are so creative, there can be a tendency to take that for granted and to not resource it at the same level that cities that don’t have it as innately as we do have to. So, that’s kind of this contradiction that, in my job, I have to push back against a lot. The attitude that, well, this is going to exist whether we support it or not, and that’s just not the way to be thinking about it. Rather, we should look at what are we already really great at? And what would it look like if we resourced it more?

What’s the difference between graffiti and murals?

You definitely need to get somebody more versed than I am to talk about that. That’s a totally subjective question. And I would say, I’m not sure. There’s a definite tendency to conflate vandalism and graffiti and graffiti art. You know? I am not well-versed enough in the sort of political history of graffiti, which is really, really rich and interesting, to speak with any authority about this. But I would say that there is a difference. There is definitely a difference between graffiti art and vandalism. And it’s not all about whether it’s sanctioned or not. But it’s a conversation we’ve been having a lot recently, and this definitely came up during the ‘Unframed’ process. One of the most challenging elements of that program, and we have it a little bit easier each time, is getting property owners on board. … The five property owners who are participating in ‘Unframed’ were not difficult to work with once we got in touch with them. But we definitely had to knock on a lot of doors, metaphorically, to get people on board. I think that as people see the incredible response and the impact of these murals, that will become less challenging.

Is it hard to get permission to have a mural painted on your building?

We, along with others, have been saying for a long time that the mural process within the city permitting is unnecessarily onerous and very, very expensive. And I don’t think any of that was intentional. It’s just what happens in bureaucratic processes sometimes.

Murals are being conflated with advertising and being reviewed like signage and there was a whole lot of things that needed to be cleaned up. And thankfully, the city leadership has taken action and now the permit fee is no longer $500. It is now $50. The permitting process makes a lot more sense. The review process is a lot more streamlined. The permitting officials are not looking at the content of the artwork to make an aesthetic judgment about it. They’re just looking to see, is it obscene and is it advertising, basically? Beyond that, it depends on where you’re located. If you’re in a historic district, there’s going to be more regulations than if you’re not. It depends on what elevation that you want to put the mural on, but I certainly have seen people and hope to see more individuals commissioning artists to put an original work of art on the side of their house or on a fence. And I love it.

I love the serendipitous nature of winding your way through the city and discovering these pieces of art.

I think that’s huge. You asked about how murals can transform communities. Obviously, murals can bring visual interest to areas that may not have a lot of that already. But beyond that, even areas that do, I think they cause you to slow down and see your city, that it can become routine. The same patterns that you take. Most of us take the same walk every time we take it, and it causes you to see your surroundings in a different way, and I think that’s really beautiful.

There’s not a ton of money to spread around between all of our competing priorities. But I think that we can do a better job of spending money that we’re going to spend anyway in an artistic way. And creating more of that sense of discovery and wonder and reflection about who we are as a community through things as simple as our sidewalks and our benches and our street lights.

Unframed presented by The Helis Foundation, a project of the Arts Council New Orleans, consists of five large-scale murals in the Arts District of New Orleans. For more information on where to find them and the artists involved, click here.

NOLAbeings

Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings

Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

Data corner: Adobe Suite (create a PDF, social media graphic, presentation, edit a photo and video

Data corner is where you go to work with analytics and top tech skills. It takes on everything from PERL and SQL to Canva and Sprout Social.

Data corner: Adobe Suite (create a PDF, social media graphic, presentation, edit a photo and video

Data corner is where you go to work with analytics and top tech skills. It takes on everything from PERL and SQL to Canva and Sprout Social.