Editor’s Note: ViaNolaVie, Krewe Magazine, and Bard Early College New Orleans partnered together in an effort to bring voices of the youth into the journalistic realm. Under the guidance of professors Kelley Crawford (Bard Early College and Tulane University) and Michael Luke (Tulane University), a composition course was manifested where students write non-fiction, New Orleans-based pieces, resulting in a printed publication (Krewe magazine) designed and published by Southern Letterpress. We will be publishing each student’s piece that was chosen for the magazine.

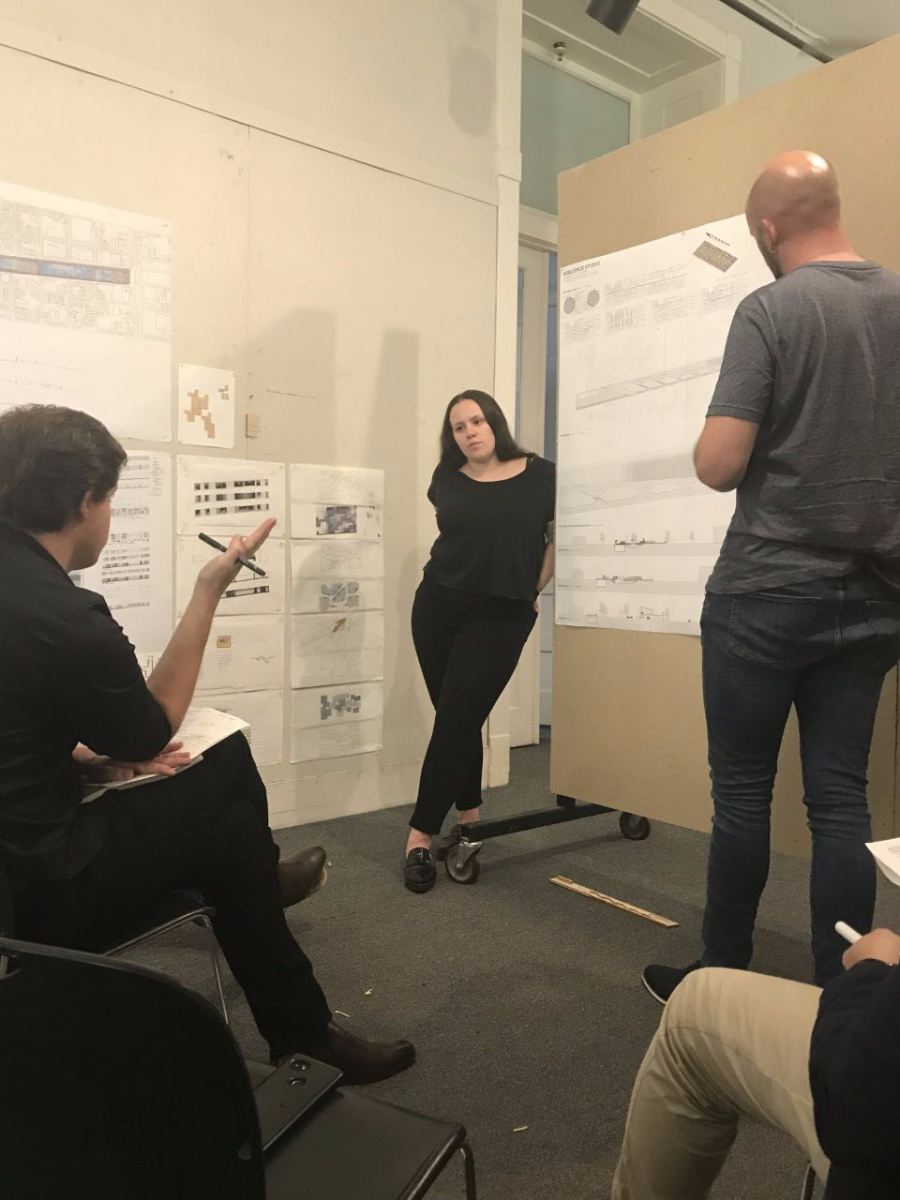

Discussions about water continue in New Orleans. (Photo by: William Potts)

For many people, flooding is a rare occurrence. For Andrea Baudy, who grew up in Gentilly and has lived in New Orleans all her life, it’s the way things go.

The 21-year-old Tulane student has witnessed firsthand the devastating effects that storms and rainwater can have on a city which lies half below sea level. Just over a decade ago, Baudy and her family fled during Hurricane Katrina. The damage to her mother’s house was irreparable.

“My mom’s house, she never moved back, it just wasn’t worth it,” Baudy said. “The effects of flooding are long lasting if you don’t prepare for them. And also for people who are poor, it could be a real bitch to try and repair your front porch or fix your wood floors. Some people have to leave or they become homeless because they can’t repair these things.”

Baudy’s mother was not alone. Five years before Katrina, the New Orleans population was estimated at close to 485,000. One year afterwards, that number had dropped to 230,000. Thousands of families fled the city never to return, with many starting new lives in locations much farther from the coast. Today the city’s population is 393,000, just 81% of its pre-storm peak.

With water levels continuously rising, engineers and designers are racing against the clock to keep the city alive.

Since that hurricane in 2005, the federal government has invested over $14.5 billion on reinforcing the levees, constructing floodwalls and additional countermeasures. Included in this total is the $1.1 billion Lake Borgne Surge Barrier, spanning two miles wide and 26-feet tall. These structures are designed to mitigate the damage of future storms and ensure that history does not repeat itself.

As state-of-the-art engineering systems and formidable walls go up, another movement is underway. Urban designers, including Tulane School of Architecture Adjunct Lecturer Aron Chang, are changing the way that water systems are viewed. The University, like many of its peer institutions across the Gulf Coast, is prioritizing water management education in its curriculum due to the local environmental concerns of rising sea levels and land subsidence.

“[We’re] really re-imagining water systems as ecological systems that can actually hold onto that water and use it… rather than just investing tens of millions of dollars every year on pumping it,” Chang said. “Which, ironically, has only exacerbated risk and raised costs over time in terms of how much we had to spend to lift water out of the bowl that we’ve created for ourselves.”

To better understand the concept Chang is discussing, consider how floodplains work. These wide areas of land next to rivers and streams act as temporary storage for flood waters and allow the waterways to spread out when necessary. This, in turn, reduces the height of flood peaks and minimizes erosion potential. Instead of an all-or-nothing approach to water management, these designers are looking into how structures and water might coexist.

The efforts could not come soon enough. Reports from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration indicate sea levels will rise three feet by 2100. That would mean daily flooding for areas along the Gulf Coast. A University of Georgia study estimates more than 500,000 people will be displaced from the seven-parish New Orleans area as a result.

During his undergraduate studies at Williams College, Chang says he was not exposed to the topics now central to his work. He cites the pre-financial crisis global building boom and “starchitecture,” where big name architects were known for their formal explorations, as being the dominant discourses of the time instead.

Yet growing environmental concerns have turned the spotlight away from celebrity architects with avant-garde designs, where the buildings themselves were the focus, and placed the landscapes center stage. The imminent threat of rising water levels in New Orleans is forcing Tulane to embrace a new environmental discourse.

“The course I’m teaching here now, Site Strategies, that wasn’t part of my school there,” Chang said. “I was in school for four years, and we didn’t have a single required course that dealt with site or landscape.”

Annie Davis, a Tulane junior and Architecture major, was a student in Chang’s Site Strategies course last year. She described how the class informed her understanding of how designers need to approach environmental concerns in their projects.

“The class taught me about the unique challenges that we as designers face in New Orleans specifically and why it is so important to understand how our buildings and materials affect the environment in huge ways,” Davis said. “It is also incredibly critical to not turn a blind eye to the evolving and changing environment around us. The Site Strategies class promotes a curiosity for how we can design better buildings that can support themselves when it comes to water retention.”

Sometimes to move forward, you have to look back. For over 800 years, the Dutch have practiced water management and created stylishly sustainable waterway systems in cities such as Amsterdam and Rotterdam. Waggonner & Ball, a New Orleans-based architecture firm, recognized this foreign success and initiated The Dutch Dialogues after Katrina.

The goal of the partnership was to bring design and water sector experts together to catalyze a water movement in New Orleans and rethink how residents can live in an urban delta. One result of the Dialogues was the funding and development of the Greater New Orleans Urban Water Plan, which began work in 2011. The plan’s website, LivingwithWater.com, outlines the goals of the initiative.

“With more than sixty inches of rain each year and growing risk posed by climate change, last century’s over-matched drainage infrastructure is inadequate to present and future challenges…With the Urban Water Plan, Greater New Orleans can directly address these challenges and make better use of its water assets, while bringing innovations in engineering, planning, and design to other coastal regions where robust water infrastructure is critical to survival and economic prosperity.

Two years after moving to New Orleans, with his Masters of Architecture from the Harvard Graduate School of Design, Chang worked at Waggonner & Ball as a design team lead and outreach coordinator for the Greater New Orleans Urban Water Plan. Following his departure from the firm, Chang served on the New Orleans Environmental Advisory Committee from 2017 to 2018 and on Mayor LaToya Cantrell’s Transition Water Plan Subcommittee in 2018.

Efforts from these and other community oriented groups look to more sustainable options of water management in New Orleans. After participating in the U.S Department of Housing and Urban Developments’ National Disaster Resilience Competition in January of 2016, the city of New Orleans was awarded more than $141 million to implement elements of its Gentilly Resilience District proposal.

This proposal includes projects and innovative solutions to reduce flood risk, slow land subsidence, improve energy reliability, and encourage revitalization across Gentilly.

The neighborhood is a particular focal point due to its storm vulnerability. Baudy, who was raised there, is frustrated with how long it has taken for action plans to materialize.

“In New Orleans there’s such a laissez-faire attitude to everything, I mean everything,” Baudy said. “So how can you make people care if nobody really cares? Why don’t we fix the subsidence problem, which would fix our flooding problem, because then we would be replenishing the dirt and sand from the Mississippi instead of just bottling it up.”

She grew accustomed to floods affecting her daily life, notably her school schedule.

“Schools here specifically have hurricane and evacuation days for days that water gets too flooded and people can’t leave their house,” Baudy said. “I didn’t realize that other people didn’t do that.”

On a Friday afternoon inside Tulane’s Richardson Memorial Hall, the home of the School of Architecture, weary students gather on the fourth floor for their mid-semester review. Many of them clutch coffees, having pulled all-nighters in preparation for the day. This particular group belongs to a design studio led by Associate Dean Kentaro Tsubaki and Adjunct Lecturer Charles Jones.

The pair received a $100,000 grant this year from the PCI Foundation to develop a class-based research project that explores the role precast water management structures may have in enhancing landscapes and supporting resilience in coastal areas.

Students of the studio are tasked with designing, fabricating, and testing scaled prototypes of precast concrete-based structures based on a particular water-based challenge. At this review, they must present their findings to date in front of a panel of their instructors and guest judges.

Anabelle Kleinberg is currently in the hot seat. The fifth-year architecture major walks her audience through the three dimensional conceptual designs she has created using computer software. Meanwhile, the judges watch intensely, their faces calm while their pens scratch furiously away on notepads. When she is finished, each judge takes a turn offering compliments and constructive criticisms to guide her project’s path.

Chang, who has worked closely with a variety of building materials in his urban designing experience, sees new possibilities in the way designers interact with concrete. Studios like Tsubaki’s and Jones’ are steps toward understanding the full potential.

“Concrete will continue to be part of the palette of materials that Architects and Engineers use in the foreseeable future,” Chang said. “But in recognizing the fluidity of the Delta, the fact that waterways want to change course and water levels are constantly in flux, how can we think of different approaches to using these harder elements? How might they be deployed along the coast and in urban settings to address the kinds of risks and vulnerabilities that we see now?”

Mimicking designs of cities like Amsterdam and forming canals is just one way that New Orleans could use concrete to reshape the layout of New Orleans. The reality, experts agree, is that the city must shift the paradigm of how it lives with water because the current path is a sinking one.

With Chang, Tsubaki, Jones and other Tulane faculty bringing environmental management strategies to the forefront of their students’ education, the next generation of architecture graduates will be armed with the knowledge necessary to instigate change and tackle these issues in the field.

As sea levels continue to rise, Baudy hopes the city can quickly find more sustainable solutions to an issue knocking on New Orleans’ doorsteps. Otherwise, it will be too late.

“For years we’ve just been putting bandaids on things,” Baudy said. “Now we’re getting to a point where we can’t ignore it…Scientists say we won’t be here in 100 years because of it. One hundred years, to some people, seems so far away, but it’s really not. It’s around the corner considering all the things we would have to put in place.”

NOLAbeings

Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings

Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

Data corner: Adobe Suite (create a PDF, social media graphic, presentation, edit a photo and video

Data corner is where you go to work with analytics and top tech skills. It takes on everything from PERL and SQL to Canva and Sprout Social.

Data corner: Adobe Suite (create a PDF, social media graphic, presentation, edit a photo and video

Data corner is where you go to work with analytics and top tech skills. It takes on everything from PERL and SQL to Canva and Sprout Social.