This story written by Matt Sakakeeny was reprinted with permission from The Lens, New Orleans area’s first nonprofit, nonpartisan public-interest newsroom, dedicated to unique investigative and explanatory journalism. The original story can be found here.

As the final notes of “When the Saints” closed out 2018, and the grand marshal put away her Tricentennial umbrella, we awoke to just another year. New Orleans is no longer 300; we are 301. The anniversary parade has passed, the panel discussions about centuries-old traditions have been archived for posterity, and it’s time we looked forward to another 300 years. Or however long we can stay afloat.

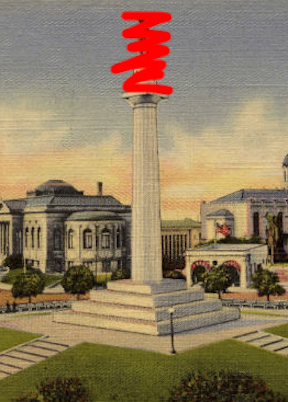

Lee Circle without Lee: a point of pride for ex-Mayor Mitch Landrieu. (Work by: Liz Tan)

Reckoning with the city’s past while gesturing toward the future is what mayor Mitch Landrieu had in mind on the eve of the Tricentennial, when he called for the removal of four Confederate monuments. The memorials to the President of the Confederacy Jefferson Davis, Commander Robert E. Lee, General P.G.T. Beauregard, and the 1874 Battle of Liberty Place were inscriptions on the very environment, spelling out for all who matters and who does not. “To literally put the Confederacy on a pedestal in our most prominent places of honor is an inaccurate recitation of our full past,” Landrieu said in a press conference on May 19, 2017. “It is an affront to our present, and it is a bad prescription for our future.” With the four symbols now removed, the question still lingering is how we distinguish the past from the present and future, the tangible from the intangible, symbolic change from actual policy.

Two recent books provide some answers.

Jason Berry begins “City of a Million Dreams: A History of New Orleans at Year 300″ by offering the monuments episode as a prismatic look into this beautiful, broken land of dreams. Landrieu appears among a cast of characters – priests and pirates, musicians and Mardi Gras Indians – who, for three centuries, have turned New Orleans’ notoriously unstable terrain into a stage for pageantries of life and death. Winding through Berry’s prologue is the 2015 jazz funeral procession for musical deity Allen Toussaint. The drama of resurrection provides a central metaphor for overcoming adversity: public mourning resolves into celebration.

The spectacle of the monuments coming down was also intended to symbolize death leading to municipal rebirth. What was meant to die with the monuments was the “Lost Cause” myth that defeated Confederates used to reestablish white might. As Landrieu spoke a crowd gathered down the street, at the circle formerly known as Lee, to watch a crane operator hoist the last of the four statues off its 60-foot column of Tennessee marble, set atop a 24-foot pedestal of Georgia granite.

The fallen soldier was laid horizontally on a flatbed truck, like a three-ton bronze corpse awaiting a mortician. A few spectators stood waving Confederate flags to the slow rhythm of an imaginary dirge while hundreds more rejoiced in the streets. The dream of removing the monuments — an act of atonement — was to clear the ground for a more just future.

The events of that day not only catapulted Landrieu into the national spotlight, they sparked a multi-state wave of monument removals and a fierce backlash from white nationalists. The backlash culminated two months later at a rally in Charlottesville, Va., where another statue of Lee was slated to come down. A neo-Nazi drove his car into the crowd, killing an anti-racist protester. Different visions of the past and the future, of the symbolic and the actual, can be a matter of life and death.

At the end of his book, Berry returns to Lee Circle and calls the mayor’s quest a turning point in the city’s history of sanctioned racism. Landrieu, who is white, had “changed sides,” repositioning the city on “the truthful side of history.” In the preceding chapters, Berry artfully condenses a sprawling series of events into a lucid, poetic narrative that extends from the French occupation of Native American territories in 1718 to current post-Katrina developments.

For Berry, New Orleans is fundamentally a land of dreams populated by waves of dreamers, starting with the European founders who conjured a colony on perilous swampland and the enslaved Africans whose freedom dreams manifested themselves, above all, as “a life force of dancing, parading, and music to resist a city of laws, anchored in white supremacy.” Most dreams remain unfulfilled. Heroes fall. People die. But, in Berry’s account, death is forever twinned with resilience. The imperative for the living is to honor the dead by continuing to chase the dream.

As a lifelong New Orleanian, Berry sees the dance of adversity and overcoming in the city’s politics, its folkways, its very ecology, and he has a Catholic’s unshakable faith that perseverance through the storm will lead everyone to deliverance. From this perspective, Landrieu extends the lineage of dreamers, not by adhering to traditions of white supremacy but by abandoning them, taking them down, changing sides.

Did Landrieu break with the past? It depends on how you see the past, not to mention the present and future. I read “City of a Million Dreams” alongside another book that covers New Orleans’ three centuries in a more sobering tone. In “Development Drowned and Reborn: The Blues and Bourbon Restoration in Post-Katrina New Orleans“, author Clyde Woods uses the 2005 hurricane as an entry point for understanding how America has “drowned” black people, both metaphorically and materially. He meticulously traces the deep history of “organized abandonment” in New Orleans, an “epicenter where racial, class, gender, and regional hierarchies have persisted for centuries.”

Woods was a professor of geography and director of the Center for Black Studies Research at the University of California’s Santa Barbara campus. After he died suddenly in 2011, editors Jordan Camp and Laura Pulido brought his final work to light. An outsider to New Orleans, Woods had an insider’s view of life as a black American. His scholarship was dedicated to excavating inequality, which he saw as both rooted in place and as dynamically regenerated or “reborn.” For Woods, adversity is not inevitable; it’s intentional, and the necessary response is not an ode to resilience; it’s rebellion.

Approaching the tumultuous period after the Civil War, when the Lost Cause mythology was incubated, Woods tracks Democrat leaders as they rise from the ashes of defeat alongside the extraordinary efforts of a Republican multiracial coalition trying to enact an ethical vision of equal rights. It’s another dream, of course. Woods calls it a “Blues agenda,” directed against organized abandonment and toward an ethics of communal care and collective redistribution.

The cultural terrain of Confederate monuments and official Mardi Gras parades was erected on this subterranean layer of legislative, juridical, and executive power, which Woods calls the “Bourbon” or “neoplantation” bloc. This foundation was destabilized by a series of federal policies that started with Brown v. Board of Education, the 1954 decision that led — slowly and incompletely — to school integration.

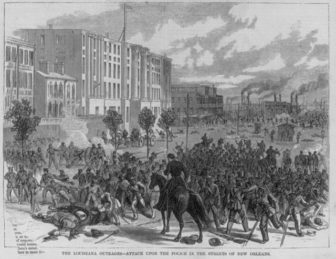

The Battle of Liberty Place marked the resurgence of violent white supremacism in the aftermath of the Civil War.

The quest for universal suffrage, citizenship, and integration was tragically foreclosed, first through force, in the 1866 Mechanic’s Hall massacre and the 1874 Battle of Liberty Place, and then through decades of legal violence. Creoles of color and progressive whites challenged the Separate Car Act of Louisiana, taking the Plessy v. Ferguson case all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, but the court decision made separation of the races federal law. The state’s “Bourbon Constitution” cut taxes on the wealthy and starved public education and social welfare programs, widening class barriers and inflaming racial divisions.

By 1970, when Mitch’s father Moon Landrieu was elected mayor, City Hall was officially desegregated. Black New Orleanians were appointed to every level of government, and a path was cleared for Dutch Morial to take office in 1978. A string of black mayors followed until Mitch, with pivotal black support, was elected in 2010.

This scan of history brings me back to the question of how the past has prepared us for the present and future, and how symbolic politics fit into larger systems of governance. The integration of City Hall marked a massive shift in representation, leaving only monuments and other residual signs of the neoplantation system for Mitch to wipe clean. Yet a narrow focus on public symbols, political representation, and racial optics misses a big part of the picture. Because we know these changes have, in fact, not yet transformed New Orleans from being an epicenter where racial, class, gender, and regional hierarchies persist.

It is one thing to recognize that Landrieu is by no means cut from the same mold as the men memorialized in the statues he took down. At least in this city, overt white supremacists are no longer viable leaders of the political regime that has taken shape since the Civil Rights era. It is another thing to applaud such changes without foregrounding the problem that concrete inequalities built into the infrastructure of the city have gone mostly unchanged. Landrieu offered no substantive policies on affordable housing, minimum wage increases, or job training and development. With tourism booming and an influx of transplants driving up housing costs, the musicians, chefs and others who form the bedrock of tourism risk being priced out of the city.

Each sector of criminal justice – the police department, the dozens of private security patrols, the parish prison, and the Public Defender’s and District Attorney’s offices – is so isolated and broken that no one seems able to imagine systemwide reform, let alone implement it. Surveillance cameras are ubiquitous. Mere mention of the Sewerage & Water Board will drive the sober to drink.

That the buzzword of Landrieu’s administration was “resilience” is telling. The term gets tossed around – not only at Katrina survivors, but service workers and culture bearers, renters and homeowners, students and teachers, ya mama ‘n ’em – as if it’s the sole responsibility of residents to overcome the adversity generated by harmful policies.

If what Woods called the Bourbon bloc is still alive and kicking, the Blues agenda is also ongoing. Organizations like the Jane Place Neighborhood Sustainability Initiative, the Worker’s Center for Racial Justice, the Music and Culture Coalition, and many others are agitating to transform the city at different pressure points. The successful campaign to remove the monuments did not start with Landrieu but with the work of activists in the 1970s (who also decried the naming of many schools and streets after white supremacists). Two of those forerunners, Malcom Suber and Leon Waters, have collaborated with Take ’Em Down NOLA, a black-led coalition that has been organizing protests since 2015, calling on the city to “take down all symbols of white supremacy.”

Take ’Em Down NOLA is an arts collective that hosts song circles, publishes underground zines, and partners with local artists like Brendan “B-Mike” Odums to wed aesthetics with activism. Their splinter organization, The People’s Assembly, is more policy oriented, mobilizing for “higher wages; affordable housing; improved public transportation; quality public education for our children and affordable health care.” They resent Landrieu for “Columbusing” their idea of removing the monuments and blame him for helping maintain policies that make life harder for most New Orleanians. Theirs is a retrofitted Blues agenda aimed at what they see as a made-over neoplantation bloc.

I can hear the city’s French founders crying from the grave: Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose (“The more things change, the more they stay the same”). But those of us looking to balance adherence to the past with productive changes in the future have a rich storehouse of knowledge to draw upon. Berry and Woods come at this history from different vantage points and immersing yourself in both of their books is time well spent.

Matt Sakakeeny is Associate Professor of Music at Tulane University. He is the author of “Roll With It: Brass Bands in the Streets of New Orleans” and co-editor of “Remaking New Orleans: Beyond Exceptionalism and Authenticity”, due out in May 2019.

The opinion section is a community forum. Views expressed are not necessarily those of The Lens or its staff. To propose an idea for a column, contact Lens founder Karen Gadbois.

NOLAbeings

Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings

Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

Data corner: Adobe Suite (create a PDF, social media graphic, presentation, edit a photo and video

Data corner is where you go to work with analytics and top tech skills. It takes on everything from PERL and SQL to Canva and Sprout Social.

Data corner: Adobe Suite (create a PDF, social media graphic, presentation, edit a photo and video

Data corner is where you go to work with analytics and top tech skills. It takes on everything from PERL and SQL to Canva and Sprout Social.