Jackson Barracks is the long-standing and current home of the Louisiana National Guard located near the heart of New Orleans. The Barracks is almost as old as the United States itself, and as such, has shared in much of America’s long (and sometimes troubled) history.

After the Battle of New Orleans during the War of 1812, the United States Congress realized that America’s coastal cities (especially the vital waterway of the Mississippi River that cuts right through the center of the nation) were not as well protected as they once thought. In response, they voted for the Federal Fortifications Act of 1832, which was signed by the Jackson administration. Andrew Jackson at the Battle of New Orleans, 1815

Andrew Jackson at the Battle of New Orleans, 1815

This Act granted more than $180,000 to the building of the New Orleans Barracks, which would later be renamed Jackson Barracks on July 7th, 1866, after the “Hero of New Orleans,” Andrew Jackson.

In 1837, the first federal troops arrived at the Barracks, which was originally designed for only four infantry companies. The Barracks has vastly changed in the nearly 200 years since its foundation in 1834[1], such as expanding to accommodate more soldiers and eventually becoming the headquarters of the Louisiana National Guard.

A host of important soldiers were stationed at the New Orleans Barracks at one time or another, such as Ulysses S. Grant, P. G. T. Beauregard, and Robert E. Lee. Many of the current roads inside of Barracks are named after some of these men, such as Lee Circle and Beauregard Drive. Photo (taken from the Mississippi River Levee) of Beauregard Drive, along with some of the original Antebellum Homes and the Parade Ground, 24 December 2012.

Photo (taken from the Mississippi River Levee) of Beauregard Drive, along with some of the original Antebellum Homes and the Parade Ground, 24 December 2012.

There is also the Barracks’ role in the displacement of Native Americans during their removal from their ancestral homelands to territories in the West. Whole Native families were hosted for days at a time in the Barracks before they were forced to the new Indian Reservations in the West.

During the Mexican-American War, the New Orleans Barracks was used as a staging and receiving ground for troops going into and returning from battle. The first Public Service Hospital for Veterans in the United States was built at the New Orleans Barracks in 1849 for wounded troops coming from Mexico[2]. This hospital treated soldiers well into the 1880s, until it was demolished after falling into disrepair during the Reconstruction Era.

In 1861, the state of Louisiana (along with other slave-holding, Southern states) seceded from the Union and joined the Confederate States of America. Consequently, the New Orleans Barracks was taken over by Louisiana state militias.

At the time, New Orleans was the largest city in the new Confederacy by a wide margin, and being a major port city at the mouth of the Mississippi River, the city (and its Barracks) fell to the Union in less than a year. Its hospital served thousands of troops during the Civil War, and the Barracks was used as a staging ground for Union forces in the South.

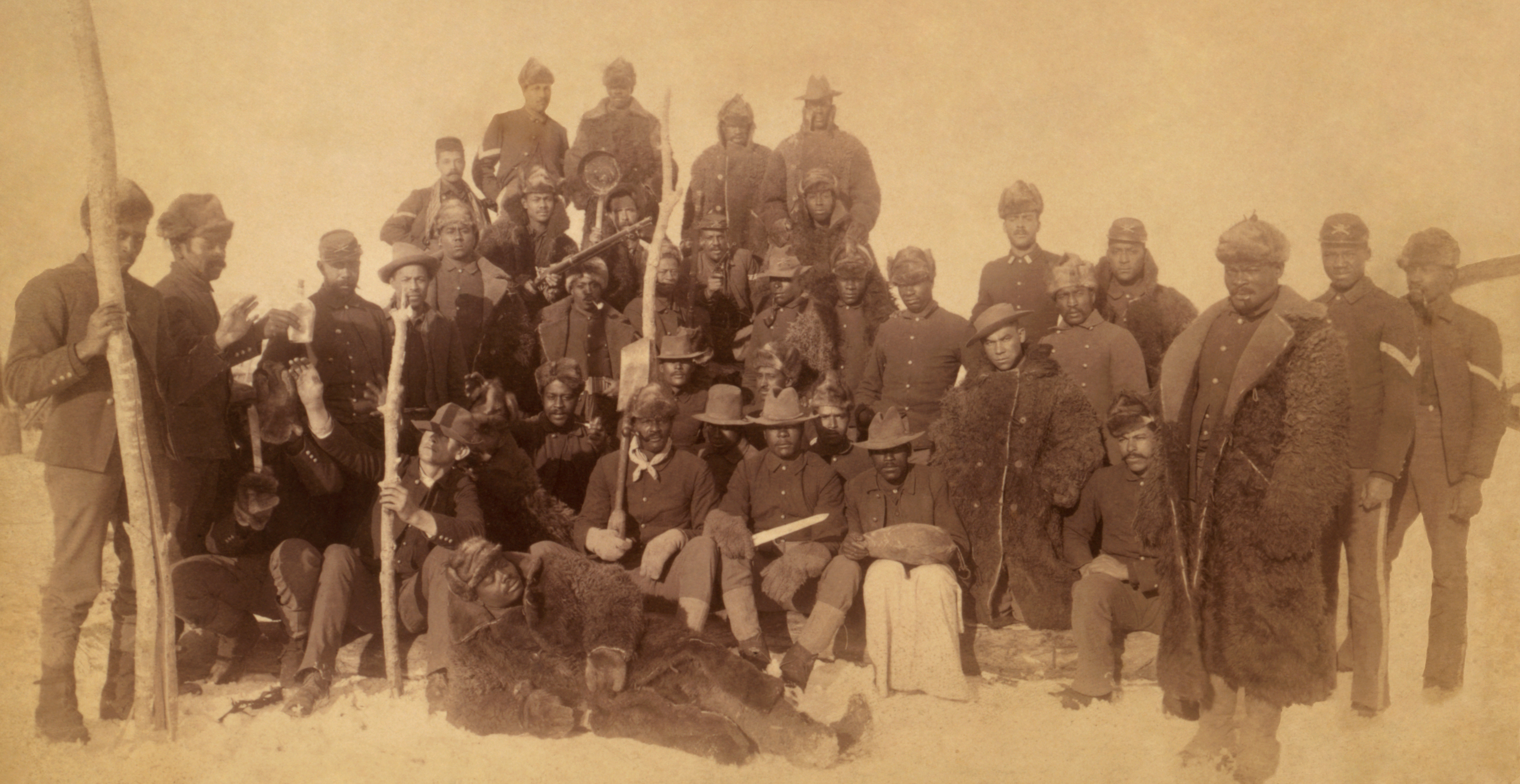

During the Reconstruction Era, four “colored” regiments of soldiers were housed in Jackson Barracks. These regiments (along with other black regiments throughout the United States) became known as the “Buffalo Soldiers” for their participation in the Indian Wars and the Spanish-American War. These prestigious “Buffalo Soldiers” would go on to fight in many future wars, such as World War II and the Korean War.

Buffalo Soldiers of the 25th Infantry Regiment, 1890

Buffalo Soldiers of the 25th Infantry Regiment, 1890

The first disaster for the newly renamed Barracks came a few years later with the Yellow Fever Epidemic of the late 1870s[3]. Most soldiers in the Barracks were evacuated to flee the epidemic. However, fifteen were left in the Barracks as a caretaker force, of whom only six survived.

Soldiers returned to the Barracks as the nation prepared for the Spanish-American War in the late 1890s. Several state artillery batteries, such as the Louisiana Field Artillery and Washington Artillery, trained in Jackson Barracks, and every year since, the Washington Artillery has held a ceremony on the Barracks as tradition.

Washington Artillery, 1862

Washington Artillery, 1862

Washington Artillery, 1917

Washington Artillery on Jackson Barracks, 2012

Washington Artillery on Jackson Barracks, 2012

Being located in New Orleans, Jackson Barracks has been involved in the New Orleans festival known as Mardi Gras. The King of the Krewe of Rex came to the Barracks by boat to be received by the Commandant with music and fanfare. The Commandant would then give control of the city to Rex in a formal ceremony, starting his reign as King of Carnival. Other entertainment on the Barracks included a popular polo field, which attracted spectators from all over Greater New Orleans.

During WWI, Jackson Barracks again became an important staging and training ground for troops leaving for Europe. The Barracks became the headquarters of the Coast Defenses of New Orleans and of the South Atlantic Coast Artillery District. The 1st Trench Mortar Battalion was formed in Jackson Barracks and participated in the Meuse Argonne Offensive during the War. General John J. Pershing, commander of the American Expeditionary Force in France, conducted a famous inspection of troops on one of the original parade grounds of Jackson Barracks in 1920.

On the left, General Pershing conducts his pass and review of the troops, 1920. On the right, the same building featuring Mardi Gras decorations in 2018.

The Great Depression hit America hard, but it was a blessing in disguise for the Barracks. After the First World War, Jackson Barracks had fallen into disrepair and was abandoned by the US Army. Huey Long, then governor of Louisiana, funneled federal money to the Works Progress Administration (WPA) to repair the Barracks (among other infrastructure projects throughout Louisiana).

The WPA completely renovated the Barracks, and built one of its most beautiful buildings called Fleming Hall, named after the first Adjutant General of Jackson Barracks, Major General Raymond Fleming[4]. Just prior to WWII, General Fleming held a Selective Service Conference on the Barracks to design how a draft would be implemented if needed. The Selective Service Act of 1948 came from this conference.

One of the two remaining original Guard towers, 15 April 2018

When the US entered WWII, the Barracks was federalized and came under control of the US Department of War. It again became a major point of embarkation for soldiers going to the European, African, and Pacific theaters.

Prisoners of war from Germany and Italy were detained in the Barracks, and hundreds of American soldiers and citizens worked there, bringing new life to the new buildings constructed in the Great Depression.

At the end of WWII, control of the Barracks went back to the Louisiana National Guard, but the federal government maintained the right to federalize the Barracks in times of war or emergency.

During the 1960s, the Barracks housed a work release prison within its walls. In the 1990s, this prison was renovated with schools, libraries, and literacy classes as part of the Jackson Barracks Prison Project started by the group Thugs United, along with Loyola University of New Orleans. The prison was closed in 1993 after three prisoners escaped and murdered a woman on the Barracks. The prison was converted and operated as a police training facility until it was destroyed in 2005 by Hurricane Katrina.

The Barracks was registered by the National Register of Historic Places in 1976[5]. A year later, one of the Barracks Old Powder Magazines was turned into the official Louisiana National Guard Museum[6]. The Museum continues to operate to the present day, and houses exhibits from the Revolutionary War to the Global War on Terrorism. It also houses artifacts as diverse as pieces of the Berlin Wall to pieces of houses destroyed by Hurricane Katrina.

On August 29th, 2005, Hurricane Katrina slammed into New Orleans[7]. The levees of the Industrial Canal were breached by the storm surge, and water flooded most of New Orleans and all of Jackson Barracks, sometimes by more than twenty feet. Citizens of New Orleans who had ignored (or were unable to comply with) the mayor’s mandatory evacuation order were transferred from the Mississippi River Levee to the Louisiana Superdome by National Guard helicopters. The floodwaters completely destroyed Jackson Barracks, and the headquarters for the LA National Guard were relocated to Camp Beauregard further inland. Soldiers keep the peace on Bourbon Street in the French Quarter shortly after the floodwaters receded from New Orleans, 2005.

Soldiers keep the peace on Bourbon Street in the French Quarter shortly after the floodwaters receded from New Orleans, 2005.

Francis J. Harvey, the then Secretary of the Army, remarked that the Barracks is “a very important piece of American history that needs to be preserved.” Besides fourteen of the antebellum homes (located relatively above sea-level being in such close proximity to the levee), the Barracks was completely rebuilt. FEMA sent $35 million for the restoration project: all office and administrative buildings were grouped together with their operational rooms above the first floor in case of future floods. Original designs and materials were used when possible.

Jackson Barracks being rebuilt with FEMA money, 29 July, 2008.

All in all, the entire restoration project cost around $325 million, including brand new housing for soldiers named the Katrina Cottages. Many of the artifacts in the Barracks museum also needed restoration, and the museum closed down for several years. In 2013, it reopened in a new complex with an exhibit showing the National Guard’s involvement in Katrina, along with an exhibit for the Gulf War.

National Guardsmen activated after Katrina.

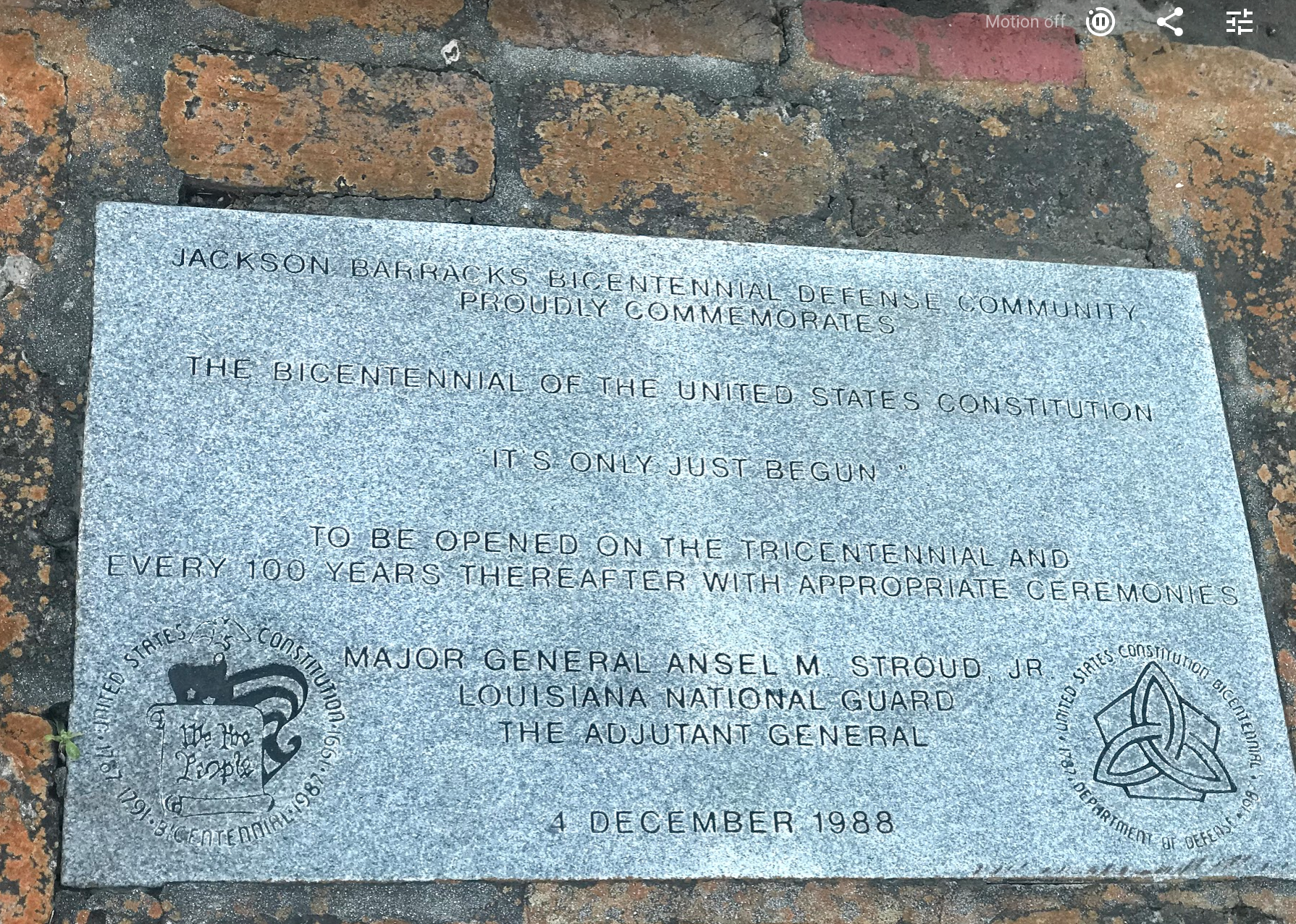

Jackson Barracks again became the headquarters for the Guard in 2010, a full five years after Katrina. It has existed for almost 200 years and was almost destroyed more than once. Each time, it has reemerged better and stronger than before while still maintaining its antebellum, Greek revival facade. A time capsule to be opened every 100 years was buried in 1980 that says “it’s only just begun.” And, to quote the LA National Guard’s official website, Jackson Barracks “serves as an enduring monument to the citizen-soldier, the military, and [the] nation.”

Time capsule located on the Barracks, 15 April 2018.

Time capsule located on the Barracks, 15 April 2018.

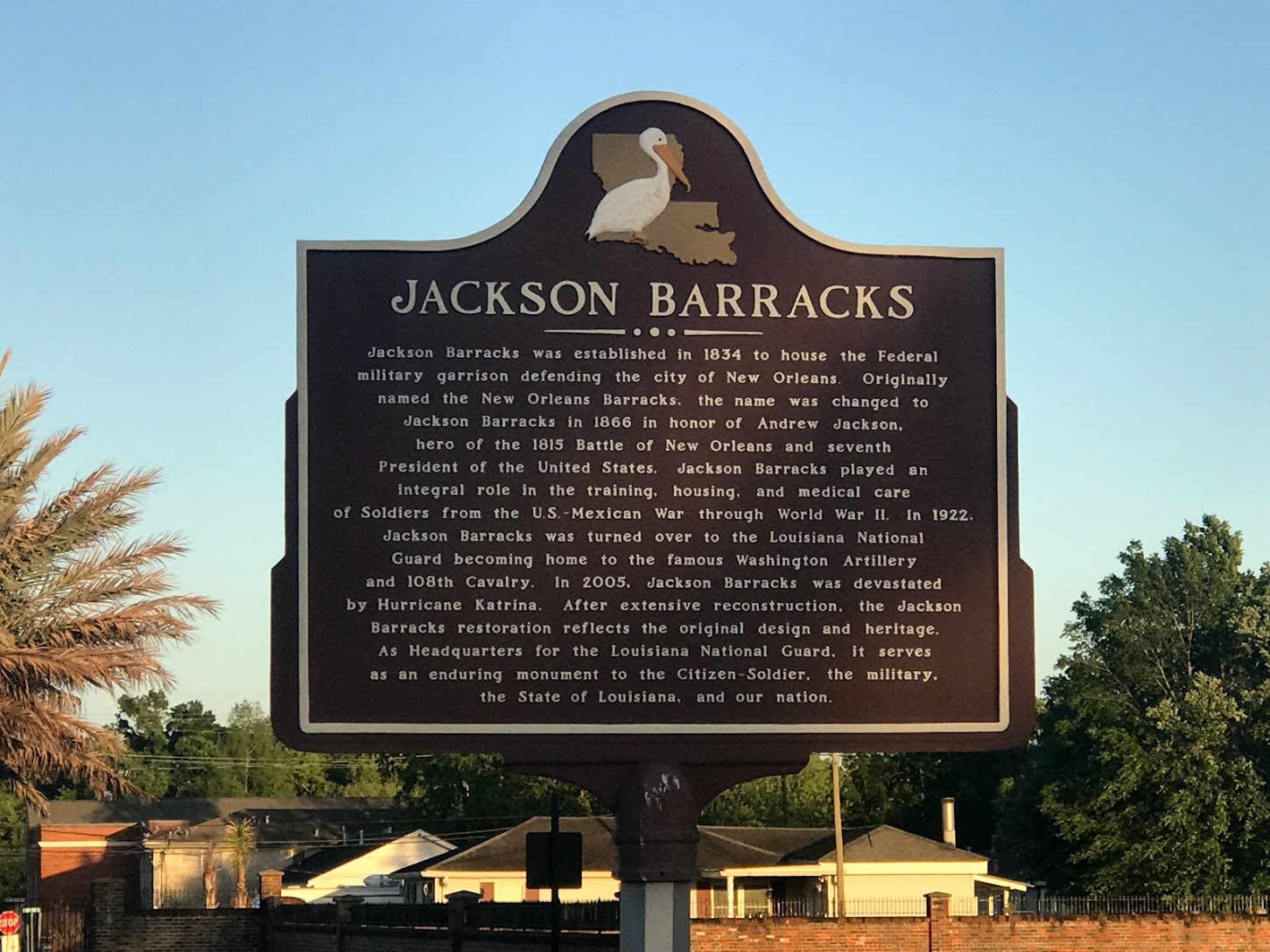

Maj. Gen. Bennett C. Landreneau, adjutant general of the Louisiana National Guard (LANG), and Governor Bobby Jindal unveil the new historic marker during the rededication ceremony of Jackson Barracks in New Orleans, 6 November 2010. The ceremony marked the official return of the LANG’s Headquarters to Jackson Barracks. (U.S. Air Force Photo by Master Sgt. Toby M. Valadie, Louisiana National Guard Public Affairs Office)

Close up of the Historic Marker.

Close up of the Historic Marker.

Photo from the Reopening Celebration, 6 November 2010.

Front Gate of the Barracks, 15 April 2018

Administrative Building on the Barracks, 15 April 2018

[1] http://www.fortwiki.com/Jackson_Barracks

[2] https://geauxguardmuseums.com/history-of-jackson-barracks

[3] http://www.myneworleans.com/Louisiana-Life/March-April-2010/Jackson- Barracks/

[4] http://neworleanshistorical.org/items/show/755?tour=41&index=5

[5] https://web.archive.org/web/20130220204509/http://nrhp.focus.nps.gov/natreg searchresult.do?fullresult=true&recordid=0

[6] http://www.neworleanshistorical.org/items/show/758 [7] http://neworleanshistorical.org/items/show/267

Article by Zachary Gandy, student at Tulane University and resident of Jackson Barracks.

NOLAbeings

Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings

Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

Data corner: Adobe Suite (create a PDF, social media graphic, presentation, edit a photo and video

Data corner is where you go to work with analytics and top tech skills. It takes on everything from PERL and SQL to Canva and Sprout Social.

Data corner: Adobe Suite (create a PDF, social media graphic, presentation, edit a photo and video

Data corner is where you go to work with analytics and top tech skills. It takes on everything from PERL and SQL to Canva and Sprout Social.

[…] This next point of interest has such a storied past, I’ll just let you read more about it on your own time HERE. […]