Sharon Litwin (photo by Jason Kruppa)

Editor’s Note: In honor and memory of Sharon Litwin, The Queen here at NolaVie, we will be publishing a piece from her every day for the next month. Sharon was an advocate and spokeswoman for arts, culture, people, and policies here in New Orleans. Her voice and sharp wit will be greatly missed.

To hear Sharon Litwin’s interview about the Kennedy assassination on WWNO radio, click here.

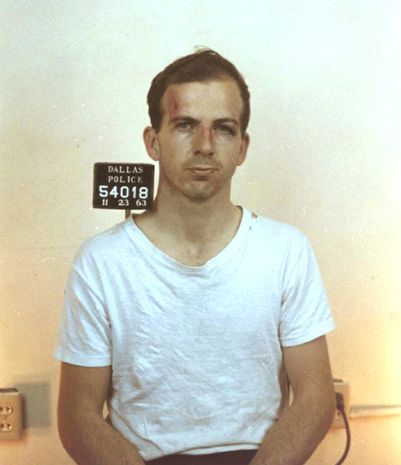

Lee Harvey Oswald, taken at Dallas Police Headquarters November 23, 1963. Credit: Dallas Municipal Archives/University of Texas at Austin.

The intense coverage of the past few weeks of the assassination of President John F. Kennedy on November 22, 1963, reveals, once again, how New Orleans was very much connected to that American tragedy. From Lee Harvey Oswald passing out Hands Off Cuba flyers on Canal Street to then District Attorney Jim Garrison’s claim that a conspiracy to kill the President started right here, New Orleans was, and forever will be, part of the Kennedy assassination story.

Most local journalists who covered it have long since passed on, but a few are still around who remember. One, Charles Ferguson, in an oral history recorded by Mark Cave, senior curator at the Historic New Orleans Collection, remembers meeting Lee Harvey Oswald in the newsroom of The States-Item, a newspaper later folded into The Times-Picayune, with Ferguson as Editor. Ferguson recalls that Oswald had come up to complain about the way The States-Item had reported a story about him. So Ferguson passed him on to the City Editor for a conversation and that, he thought, was the end of it. One month later, when news of the assassination broke, Ferguson realized the significance of that newsroom encounter.

“As far as we knew it was a huge national story,” Ferguson recalls, never thinking New Orleans had a connection, “until I saw Oswald on television. I called Walter Cowan, the City Editor, and said, ‘Do you know who this guy is? This guy was in our newsroom a month ago; this guy was living in New Orleans.’”

So out into the streets spilled all the States-Item journalists. But wherever they went, the New York Times had already been there. It was, Ferguson recalled, evidence of why, in his opinion, the New York Times is the greatest newspaper in the world. “I mean, they had a dozen people here; they had more people covering the story than we did.”

While the New York Times beat out local newshounds on the Oswald connection, three years later, it was States-Item reporters Rosemary James and Jack Wardlaw who scooped the next big story. In 1966, when rumors were rife around the Criminal Courts Building that Garrison was investigating the assassination, Rosemary asked him for an interview. He said no.

So they started to do their own research and discovered all sorts of expenses paying for investigators going to and from Dallas for who knows what reason. They decided there was enough there to print a speculative story. When it was published, Rosemary says, “all hell broke loose and journalists from all over the country came in. He (Garrison) was in hog heaven. He got all the headlines he ever wanted for a while.”

But interest waned and, Rosemary says, every time the media would back off, Garrison would come up with a new conspiracy theory.

“We started calling it ‘Garrison’s Theory du Jour’,” she says, “ because he would call a news conference and he would have a new theory about exactly what happened, the most ridiculous of which was 14 Cubans shooting from the storm drains of Dallas and catching Kennedy in a triangulation of cross fire.”

Ultimately, the most stunning of Garrison’s theories was the arrest of distinguished New Orleans businessman Clay Shaw for conspiracy to commit the murder of President Kennedy. The arrest caused a sensation, not only in New Orleans but around the world. Journalists hurried back to New Orleans, everyone believing Garrison must have some overwhelming evidence to make such a claim.

The trial began, and as the world’s journalists flocked to the courtroom, they watched as it turned into a surreal drama of the bizarre. Rosemary James went every day for six weeks. She says it was a circus.

“In those days, it was not required under Louisiana law that the District Attorney provide a list of witnesses to the defense. Well, Tom Bethel, a British guy who had gone to work for Garrison’s office just to earn some money while he was in New Orleans researching jazz, realized what a travesty was going on in this office, and he turned the list of witnesses over to the defense.”

At first blush some of Garrison’s witnesses appeared quite credible on the stand. It was on cross examination, the defense having had access to the list of witnesses and time to prepare that, Rosemary says, “to a man, they all fell apart.”

Feelings ran high in New Orleans, a community almost evenly divided as to Clay Shaw’s innocence or guilt. It was no different in the States-Item newsroom, where Rosemary recalls it was pretty much a circus as well.

“There were two reporters on The States-Item who were total acolytes,” she says. “They believed every word that came out of Garrison’s mouth, and any of us who disputed anything that Garrison said were accused by them as being part of the conspiracy. Then there were those who were trying to be objective — to present whatever Garrison put on the table. And then you had those who didn’t even want to talk about Garrison; they thought he was such a fool.”

It took the jury less than an hour to declare Clay Shaw innocent. And hardly any time at all after that for Garrison to re-arrest Shaw for perjury, a charge thrown out by Judge Herbert W. Christenberry.

Perhaps in another city, the likes of District Attorney Jim Garrison might have disappeared to lick their wounds. Not here. Not only did Garrison run for re-election; he won. While he lost the next time around, he just kept going, running for judge and winning again.

So what does Rosemary James think of this half-century-old story, one fit for a full-scale opera?

“Well, it was a remarkable story,” she says. “It was just another example of New Orleans theater. I really believe that everyday life in New Orleans is a stage play. New Orleanians are constantly re-inventing themselves as new and interesting characters when they get bored with the old character. And Garrison was no different. I think the story could not have happened the way it happened anywhere except in New Orleans.”

NOLAbeings

Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings

Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

Data corner: Adobe Suite (create a PDF, social media graphic, presentation, edit a photo and video

Data corner is where you go to work with analytics and top tech skills. It takes on everything from PERL and SQL to Canva and Sprout Social.

Data corner: Adobe Suite (create a PDF, social media graphic, presentation, edit a photo and video

Data corner is where you go to work with analytics and top tech skills. It takes on everything from PERL and SQL to Canva and Sprout Social.