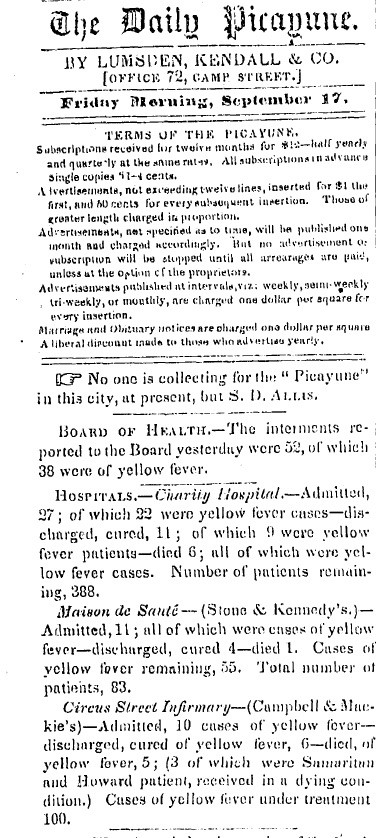

Caption: Piece from Times-Picayune archives of September, 1841

Throughout history there have been various epidemics such as smallpox, Spanish flu and the scarlet fever. During the 1800s, New Orleans was one of the states in the United States that was hit with the yellow fever epidemic the worst, causing over 40,000 casualties. As this was occurring, from the 1830 to 1850s, the shipping and transportation industry was expanding rapidly in New Orleans, bringing people and supplies from various countries such as England and Ireland as well as Northern states to the ports of New Orleans. Due to the influx of people coming in and out of New Orleans and the booming transportation industry during the heights of humid and hot temperatures, Yellow Fever was uncontrollable and lasted throughout the city for several years.

The Yellow Fever has subsided its abundance in the United States recently; yet, back in the 1800s, the fever was extremely prominent. The fever stems from an infected mosquito and once a person is bit by the mosquito, the virus ends up in the body. The fever is not contagious and cannot be spread person to person unless through direct contact with the bloodstream. The side effects of yellow fever are easily noticed. As soon as the virus is contracted, victims experience several unpleasant symptoms . To name a few there are chills, nausea, fever, delirium and convulsions. Worst of all there is blood. These symptoms can be commonly mistaken for symptoms of the flu making it harder to distinguish that people were actually infected with yellow fever, hence the continuous spread as people were not isolating themselves as people that were living in close quarters both on the boats as well as when they got to New Orleans.

Yellow fever was spreading throughout New Orleans for several years. At points there were bad breakouts as nearly 30-40 people were admitted to hospital each day or there were minimal breakouts where 5 or fewer people were admitted. What increased the breakouts were the amount of people coming in and out of New Orleans through the increase in the shipping industry and the regular schedule of the arrival of steamboats coming in and out of the city with passengers as well as various items. In the early 1800s, New Orleans recorded 45,000 people residing in the city. After the Mississippi River Trade expanded so did the number of people living in New Orleans. Whether it be people traveling with European countries such as Ireland and England to travelers from the northern states of America, the population of New Orleans increased substantially. By the middle of 1850, the population of New Orleans rose to over 170,000 people. Not only were the streets more crowded with people yet the population made people more susceptible to widespread illness.

The ports of New Orleans were highly populated during the 1800s. A facet of New Orleans that was growing during the 1800s was the shipping and boating industry due to its location on the Mississippi River. New Orleans grew at a faster rate than any other American City, and the making and usage of boats did as well. In 1812, the first steamboat came down the Mississippi River and from that day each year more and more boats arrived. In 1821, 287 steamboats arrived, by 1826, 700 steamboats had come through and by the 1850s, an average of 3,000 steamboats a year were coming in and out of the city.

Caption: Piece from Times-Picayune archives of September, 1841

The steamboats provided a more efficient method of transportation for cotton as well as people traveling from places around the world. Around 1830, steamboats were in a regular rotation that there were two way packet lines to operate properly. The steamboats had specific days that it docked and departed the ports. For example, The steamboat Robert Fulton, leaves the city every Sunday and Wednesday at 10 o’clock AM for Bayou Sara. The boat then returns every Monday and Friday at 10 o’clock AM. Steamboat Robert Fulton is used for both freight or allows passengers on board (Daily Picayune, September 3, 1841 page 4). In and out of those lines were both cargo boats as well as passengers. But, we haven’t even gotten to what happened on the boats.

Conditions on the steamboats were not very sanitary unless individuals were staying in the upper level of the boat. As a lower level passenger, one was riding with hot boilers, livestock and other passengers. The area was crowded, dirty, sweaty but mostly smelly. These conditions easily permitted the spread of disease as there was no fresh air and people were close together. Through the influx of travel, the spread of the virus continued as more and more people were coming into the city that were not as immune. New Orleanians that had been in the city almost their whole lives were able to respond positively to the virus while the Europeans and other travelers had a more difficult time coping with the yellow fever. They had less contact with it. New Orleanians had already been exposed to the fever as it stemmed from the Caribbean and most slaves working in New Orleans were from the Caribbean. Travelers were the ones that brought the virus over as they were the people that were not able to fight it off. Due to this reason, the virus is also known as the stranger’s disease. The new transportation systems helped the economy but did not help the population of New Orleans as they were constantly stricken with the fever for many years (Times-Picayune_published_as_The_Daily_Picayune.___September_3_1841 (4))

There were several years where the pestilence grew and worsened. The worst years were the years 1833, 1837, 1839, 1841 and 1847. The summer and early fall of 1841 was especially bad as each day more and more people were dying. Yellow Fever spreads through the bites of infected mosquitoes and the increase of mosquitoes occurs when there is humidity within the air. New Orleans is ranked as the American city with the highest relative humidity level. New Orleans experiences higher levels of moisture in the air furthering the fact that more mosquitoes are present during the summer and fall times where the fever was most prevalent. In months, the weather can hit up to the mid 90s, and the humidity levels rise to higher numbers. In the Daily Picayune of September 1841, the amount of hospitalizations were reported daily. Specially on September 2nd, 37 people were admitted to three different hospitals diagnosed with yellow fever (Daily Picayune, September 2, 1841, 2). A few days later, on September 7th, from Saturday at noon until Monday, 28 people had died from yellow fever. That day, 17 people were admitted for cases of yellow fever. Circus Street Infirmary, had 65 people being treated specially for yellow fever (Daily Picayune, September 7, 1841, 2) . By mid september the number of cases per day increases exponentially. From all three hospitals, Charity Hospital, Maison de Santé and Circus Street Infirmary, there were 38 cases of yellow fever (Daily Picayune, September 17th, 1841, 2) Eventually by the end of September numbers decreased, yet the city was still stricken.

The areas hit hardest with yellow fever were the parts of New Orleans where the sailors, immigrants and boat workers went to dock after landing in the ports. First off, with the introduction of high pressure engines the steamboats were able to travel extended ranges and with that being said, the Mississippi was an overload for half the country. Gallatin Street is a particular area where the virus was heavily spread. The location so close to the Mississippi made it the perfect spot for sailors to find housing. This area was also home to many bars for people to get drinks and be entertained. Gallatin Street was very undesirable so the people who had just arrived from various cities and or countries occupied the remaining buildings and lived in them. The virus attacked the area creating a whole concentration amongst the people living on Gallatin Street. People were living in close quarters and since the people who frequented this area were not immune to the fever, it was easy for the virus to spread.

The high levels of humidity which lead to the influx of mosquitos not only enhanced but assisted in spreading the virus subsequently more as tourists came into New Orleans through the recently built and developed steamboats. As the city grew in number, the number of hospitalizations grew. Looking back on all the deaths of New Orleanians, was the continuation of traveling and the shipping industry truly beneficial to the city?

This piece is part of the “Archive Diving for Future Clarity” series for the Alternative Journalism class taught by Kelley Crawford at Tulane University.

NOLAbeings

Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings

Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

Data corner: Adobe Suite (create a PDF, social media graphic, presentation, edit a photo and video

Data corner is where you go to work with analytics and top tech skills. It takes on everything from PERL and SQL to Canva and Sprout Social.

Data corner: Adobe Suite (create a PDF, social media graphic, presentation, edit a photo and video

Data corner is where you go to work with analytics and top tech skills. It takes on everything from PERL and SQL to Canva and Sprout Social.

A powerful and well-researched piece that vividly captures the intersection of public health, urban growth, and transportation in 19th-century New Orleans. The historical lens on yellow fever and its social impact is both haunting and deeply insightful. Teacher Loan Forgiveness Program