The drums are beating, signaling the start. Excitement hangs in the air, thickening with each new beat. Enslaved people and free people of color from throughout New Orleans have arrived. It’s Sunday, and Congo Square is coming alive. On a different street block, outside the realm of the vibrant Congo Square, a group of white men marvel at today’s medical ads in the September 1841 Times-Picayune (The Daily Picayune). They exclaim their excitement over their desire to purchase a new syrup that will cure everything from the common cold to cancer.

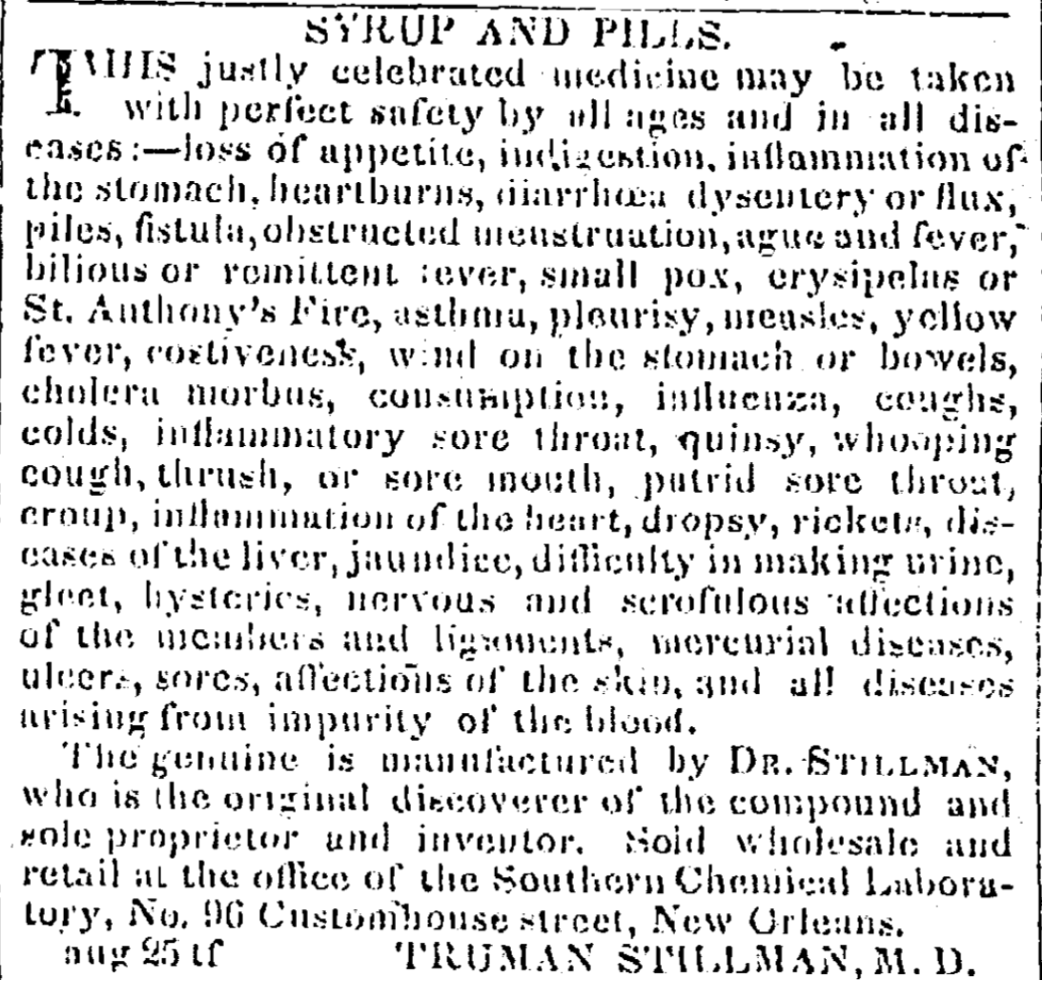

Syrup and pills article posted in the Times-Picayune, September 30, 1841. (Photo by: Times-Picayune)

The dismissal of the healing practices of the African Americans in Congo Square, despite these practices’ effectiveness, reveals that the medical system in New Orleans in 1841 valued the sale of pharmaceutical products rather than holistic healing.

Approaching Congo Square, it was common that “several clusters of onlookers, musicians, and dancers…represented, in the early decades, tribal groupings, each nation taking their place in different parts of the square.” The Sunday “day of rest” was filled with anything but rest in the bustling square. Music, dancing, and shouting filled the air as many enslaved people felt freedom for the first time that week. The exchange of coffee, pies, roasted nuts, and calas provided economic opportunities and social companionship. The money people earned selling in Congo Square provided a glimpse of economic independence which helped to mitigate the negative effects of financial stress on the body and mind. Additionally, these sales provided funds to purchase remedies from others in the Square.

How do these gatherings link with medicine? Turns out, being religiously engaged is linked to lower levels of anxiety and depression and improved general health compared to those who are not spiritual. Specifically, Voodoo rituals in Congo Square were used for both preventative medicine and for healing the sick, but were a forbidden topic in white society. Although Voodoo rituals included plants and herbs (turmeric, ginger, cluster yam, and spear grass), the religion emphasized spiritual healing as much as physical healing. This holistic approach to healing is now becoming widely accepted as a means to cure the body, and researchers have compared ritual practices like Voodoo to psychotherapy in order to explain how it can promote healing.

West Africans not only brought seeds, such as benne seeds, okra, and kola nuts from their home countries, but also the knowledge of how to use these items in healing practices and within dishes. Bargaining these plant-based products in Congo Square spread the availability of the healing properties they contained. However, healing is deeper than what is put in the body—it is also about what is done to and with the body. Nkisi were worn during congregations at Congo Square to bolster people’s spiritual healing and good fortune. The performance of the Bamboula and the beating of instruments modeled after the long and narrow African drums allowed the enslaved community to unite around music. Dance became each person’s free conduit for healing, as traditional African dance is connected to spirituality and healing. The many tribal nations respected each other within the bounds of Congo Square, but outside of these bounds, the food, music, and religious practices were invisible.

Congo Square in 1840s New Orleans. (Photo by: Annalise Rotunda)

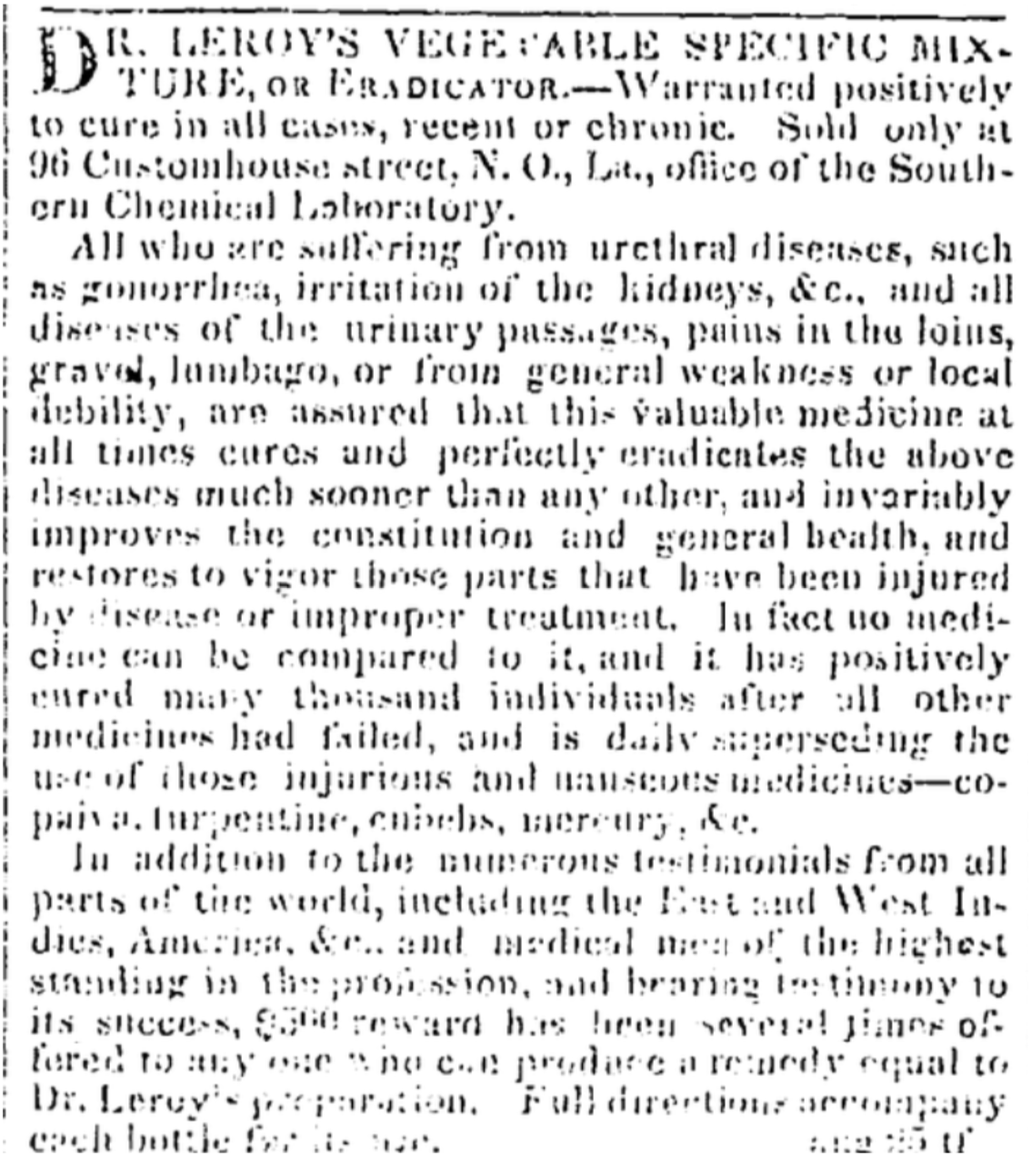

In the 1800s, New Orleans’ swampy weather was the perfect breeding ground for mosquitoes to carry viruses and bacteria throughout the city. The white people of New Orleans turned to their papers to provide them with the latest news on how to cure the incurable. Ads bragged in the Times-Picayune September 1841 publication, “It has the same success no matter what the disease may be, whether a sore or ulcer, a tumor, gout, nervous pains…cancer, or any other cutaneous affection” (The Vegetable Specific). The white man was provided everything from soda to opium to treat his many plagues, and it was often difficult to distinguish doctors from quacks and advertisements from editorials. Specifically, in 1841, advertisements in the Times-Picayune for medical “medicines of wonder” commonly read: “This justly celebrated medicine may be taken with perfect safety by all ages and in all diseases: loss of appetite, indigestion…diarrhea…influenza, whooping cough, thrush…and all diseases arising from impurity of the blood” (Syrups and Pills). Promotion of this type of “healthy living” through pills and syrup was a daily occurrence in at least one column of the front page of the paper in September 1841.

Dr. Leroy and Dr. Stillman from Southern Chemical Laboratory on Customhouse Street are repeat advertisers, distributing syrups and pills at both wholesale and retail pricing. Ads like these were common across the country, as they scored major revenues for newspapers and promised reimbursements of up to $500 if the medicine was ineffective. Historically, “patent medicine makers were prolific advertisers, and at the turn of the century, ads for their products accounted for roughly half of newspapers’ entire advertising income.” Literacy was a privilege given to white people, and elite white doctors exploited this with their prolific and exaggerated advertisements. Money dominated healthcare as “minimally-trained doctors opened their own medical schools as money-making ventures encouraged by a growing commercial and acquisitive social climate.”

Dr. Leroy’s Vegetable Specific Mixture posted in the Times-Picayune, September 25, 1841. (Photo by: Times-Picayune)

During the 1840s, the readership of the Times-Picayune was so popular that newspapers were published sometimes twice a day and in numerous languages (including English, French, German, Spanish, and Italian). As newspapers in 1841 were the primary source of information, doctors knew they had a captive audience to pedal claims of short-term solutions to serious illnesses. Long ads and these lengthy claims helped to build the impression that the products sold were scientifically valid. Expressing disapproval of African religions and practices made their medical exaggerations seem more plausible.

In the late 1890s, gatherings in Congo Square were suppressed after its renaming to Beauregard Square. However, in 2011, it was renamed Congo Square, yet there are no longer drum circles, bartering, and official events celebrating its history are sparse.

This piece was edited by Lily Plowden as part of Professor Kelley Crawford’s Digital Civic Engagement course at Tulane University.

NOLAbeings

Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings

Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

Data corner: Adobe Suite (create a PDF, social media graphic, presentation, edit a photo and video

Data corner is where you go to work with analytics and top tech skills. It takes on everything from PERL and SQL to Canva and Sprout Social.

Data corner: Adobe Suite (create a PDF, social media graphic, presentation, edit a photo and video

Data corner is where you go to work with analytics and top tech skills. It takes on everything from PERL and SQL to Canva and Sprout Social.