Orleans Parish Prison

Photo By: William Widmer

During the 1950s in the U.S., there were more than twice as many people in public mental hospitals than in prisons. Today, there are twice as many individuals with mental illnesses living in prisons than there are in psychiatric hospitals.

The evolution of the Orleans Parish Prison to the Orleans Justice Center is particularly notable. In 2012, the Orleans Justice Center was described during litigation: “people living with serious mental illnesses languish without treatment, left vulnerable to physical and sexual abuse,” and yet, today, the jail remains “critically unsafe for inmates and staff” and struggles to meet basic provisions, according to many monitors.

Colby Crawford was a 23 year old black man in New Orleans, arrested for allegedly hitting his mother and sister. Before incarcerated, Crawford was diagnosed with “seeing spirits and ghosts, insomnia, anxiety, paranoia and bad dreams,” and was prescribed an antipsychotic and anticonvulsant. However, once transferred into the OJC, Crawford was not provided with medication, as well as was denied transfer to a psychiatric tier, despite the fact that he specifically asked for help. It was made clear that the medical staff working at the OJC was entirely aware of Crawford’s “declining condition”.

Furthermore, in 2016, Jacquin Thomas, a 15-year-old black male was deprived of his prescribed antidepressants while incarcerated in the OJC. He eventually hung himself, again, due to the lack of mental health resources provided.

Cases such as Thomas and Crawford represent the typical prisoner within the Orleans Justice Center. One common theme with many of these cases is exemplified through something prison attorneys call the “yo-yo effect.” The yo-yo effect occurs when a convicted criminal is deemed too incompetent to stand trial and thus, is sent to a forensic hospital for treatment. After the individual is claimed to be “treated,” they are sent back to the prison, to which they are, again, deemed incompetent for trial and sent back to the hospital. Hortenstine, a senior attorney for mental health litigation, said, most of these yo-yoing clients are never found competent for long enough to make it to trial. Specifically in 2016, 302 inmates in New Orleans were deemed incompetent for trial, delaying their court date. Prison systems cultivate an environment for disadvantaged groups to increase their jail time, instead of helping human beings claim redemption and receive their human right to be treated for illnesses.

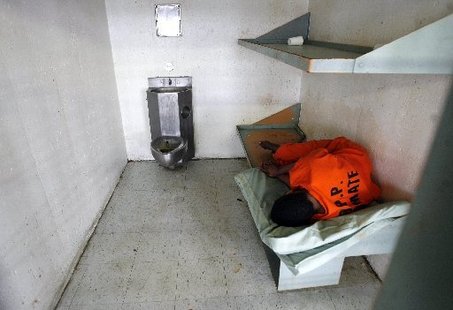

Inmate Sleeping in the Psychiatric Section of Orleans Parish Prison.

Photo By: Michael Democker

The racial disparities within mental health services begin far before individuals are incriminated. For example, New Orleans lacks proper and plentiful mental health care services, especially for the black community, even though black people make up 60% of the population in the city. From the years 2005-2007, the prevalence of reported serious mental illnesses increased around 13% in the Orleans Parish. Despite this increase, the number of beds physically declined from 134 adult beds to 20 available adult beds. Also, during this time, many acutely mentally ill citizens were placed in the parish jail for treatment, instead of a proper hospital. According to a provider, currently, “here in New Orleans, sadly the jail is the largest mental health provider in the city”; the nearest mental hospital is located in Jackson, Louisiana—115 miles outside of New Orleans. Essentially, we are incriminating citizens simply for having a mental illness, which almost every American holds.

Beyond the clear lack of facilities in New Orleans, the sheer cost of mental healthcare poses a massive problem for many citizens, especially minority groups. In New Orleans, 60% of their citizens rely on Medicaid. Despite this, Medicaid does not cover the costs of mental health facilities. For example, a media campaign by the Times-Picayune reported that a “24-year-old with severe and persistent mental illness, stated his son was number 51 on the waitlist to get into a long-term treatment facility outside of the city and even then, if he did make it to the top of the waitlist, Medicaid refused to cover an ambulance ride to the facility.” On top of this, black individuals under 18 years old are three and a half times more likely to be uninsured than white individuals, forcing a high risk among the black community to develop mental and physical illnesses.

Overall, the likelihood of an individual committing a crime entirely increases when the individual has a mental illness and is not receiving any or proper care. In a study conducted with 22,000 people entering jail, it was concluded that the basic screenings simply do not catch mental health issues for black and Latino prisoners. This poses a major issue, especially as within the Orleans Justice Center, more than 90 percent of inmates are black young men. Additionally, according to the Visions Journal, “continued incarceration often places an individual at risk, at times with tragic results and at the expense of both their physical and mental health”. As many individuals, especially minorities, are increasingly incarcerated due to low-level crimes and mental health issues, being placed in a prison system that directly fails them and puts them at high risk for danger is directly inhumane. Simply put by John Snook, executive director of the nonprofit Treatment Advocacy Center, “Even the best-funded jail, with the most effective mental health services in the country, is still a failure.”

NOLAbeings

Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings

Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

Data corner: Adobe Suite (create a PDF, social media graphic, presentation, edit a photo and video

Data corner is where you go to work with analytics and top tech skills. It takes on everything from PERL and SQL to Canva and Sprout Social.

Data corner: Adobe Suite (create a PDF, social media graphic, presentation, edit a photo and video

Data corner is where you go to work with analytics and top tech skills. It takes on everything from PERL and SQL to Canva and Sprout Social.