Dating back to the 19th century and transcending into today, sports – whether recreational or professional – have crossed economic and racial lines in terms of the audience, but have reinforced them in terms of the participants. Today, there is a distinct difference in the sports the elite-class chooses to participate in versus the middle- to lower-classes. Upper-class communities are more inclined to play a sport like golf – in which country club membership fees, golf club and gear purchases, greens fees, etc. would add up. In contrast, lower-class folks are more likely to play sports such as basketball and soccer, where only a ball is needed and goals can typically be found in public parks in urban communities. Accessibility and resources are major factors into which activities certain communities engage in, largely in part due to their economic standings. Pre-Civil War, New Orleans had the largest population of free people of color and served as a haven for clouded, vague racial categories and roles. Sports in New Orleans – specifically horse racing, rowing, and ballroom dancing – demonstrate the distinct, yet also blurred, social, economic, and racial lines of society.

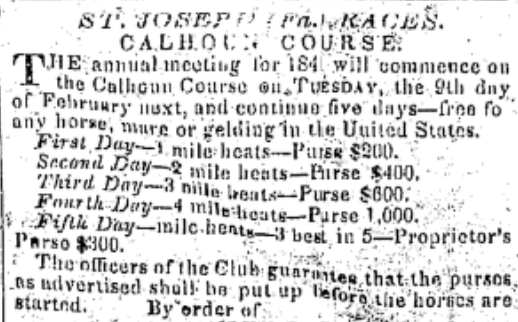

Horse racing, both in the 1800s and today, maintains its role as an elitist sport known as entertainment for rich, likely white, people. New Orleans served as a leading horse-racing center in the United States in the mid-19th century. Just as the Kentucky Derby today holds payouts for its winners in sums of millions of dollars, there were cash prizes for the winners of the New Orleans races in 1841. Relatively speaking, these were much smaller sums in contrast – varying from $200 to $1000.

Ad detailing the cash prices for the horse race from the Times-Picayune archives, January 1841

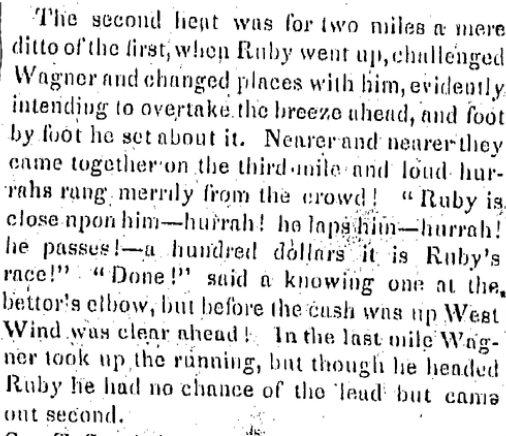

Pre-Civil War, Southern aristocrats chose to train their young male slaves to serve as jockeys for their horses and free Blacks in the North gained employment as riders. This unexpected level of inclusion, specifically from the Southerners, may explain the anonymity of the riders within newspaper articles. Articles instead cited the horses’ names, rather than those who directed the horses. These horses were used as means to an end for their owners – the end being their cash prize.

Article highlighting the recent horse race from the Times-Picayune archives, January 1841

Yet, because of their inclusion in the sport, Blacks emerged as some of the most talented horse racers and trainers, eventually giving rise to one of the most famous – Isaac Murphy. At a time in which Blacks dominated the sport, Murphy, the son of a former slave, was seen to be one of the best – he went on to win 44% of his races. This domination was rather short-lived. After the Civil War, there was a mass effort to drive Blacks out of the sport altogether and it was, sadly, successful. The increasing pay of riders encouraged the entrance of even more white jockeys into the sport who resorted to violence in the form of running Black riders into the rail and hitting them with riding crops. This increased violence motivated horse owners to contribute to the expulsion of Blacks from the sport by denying them rides. Even those of a lower socioeconomic class were able to hold informal races for their communities pre-Civil War. After, due to the creation of betting systems within the sport, the horses and the sport moved into the realm of wealthy families, while working and lower-middle classes served as the predominant audience. The focus on the horse rather than the rider, the threat white riders faced as pay began to increase for their Black counterparts, and the betting systems put in place are all examples of how New Orleans society valued their economical success over every other aspect of culture. Even in the sports industry, the true value of the sport lied with those in power to continue creating monetary gain in their field – white, landowning men.

Rowing, on the other hand, moreso appealed to those who lacked money and leisure to own expensive sailing boats, particularly young middle-class folks. Unfortunately, this sport came with a risk of high waters and floods due to the close proximity to the water, which ultimately put a halt on the sport after a devastating flood in 1844. The inability to continue the sport sparks a clear contrast between the continuity of horse racing and those that participate. The sport aimed at upper-class entertainment, horse racing, was able to carry on throughout the 19th century, while the sport directed towards the middle-class, rowing, appeared to have two major pauses within the same century. One pause was aforementioned due to the flood and another occurred during the Civil War. The disparity in the continuity of these sports displays the overall increased value of elite classes and the money they provide to society compared to lower classes. Once the New Orleans Rowing Club was formed on the Mississippi River in April 1869, the sport reemerged stronger than ever. Rowing received a height of sports media attention and, after its reemergence, remained one of the country’s most popular sports. Given the conflict within the country, rowing provided an outlet and a distance to the tension present. At an awards ceremony for a New Orleans regatta, Louisiana Speaker of the House, R.N. Ogden, gave a speech emphasizing that the athletes’ “sinewy forms and muscular physiques speak of the hardy race whose sons they are,” speaking to the attitudes of white superiority at the time. The first Black rowing club was not established in New Orleans until 1874 with the establishment of the Antoine Rowing Club. While this delayed Black inclusion into rowing contrasts the early inclusion of horse racing, it furthers and reinforces the economic placement of Blacks in society. The upper-class forced Blacks out of “their” sport out of perceived threat and hopes of capital gain, while the middle-class (although delayed) allowed the inclusion into their sport eventually.

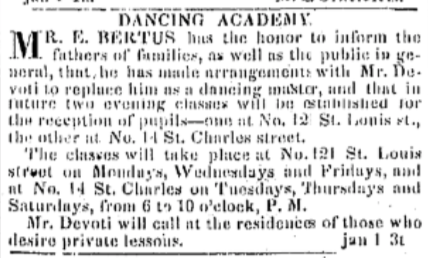

Though considered a social practice in the 19th century, ballroom dancing in today’s society represents an alternative sporting practice – one that includes an artistic element as well as the physical. Yet, in New Orleans and around the country, the physical element was ignored in pursuit of the social symbolism this practice represented. With the emergence of the Congo Square in New Orleans, slaves and free people of color had a place to gather and dance, particularly in styles relating to their African culture. The African style of dancing, along with the emergence of jazz music, is a stark contrast to the classical ballroom dancing found in New Orleans balls and Mardi Gras Krewes. In the Congo Square, there was no specific instruction or way to perform. New Orleanians were able to express themselves as freely as they wished, with little to no social implications. Ballroom dancing, on the other hand, was found in specific social practices – debutante balls included – and followed a precise level of instruction that still stands today. Trained lessons were offered to members of the New Orleans community in 1841, emphasizing the social practice’s increasing importance at the time.

Ad for dancing lessons from the Times-Picayune archives, January 1841

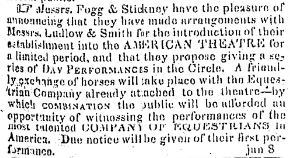

Though ballroom dancing’s social hierarchies have since blurred drastically, it was a practice for the privileged. In 1841, it also served as a form of entertainment and leisure for the upper classes, in which they were able to watch their daughters become women at debutante balls or enforce standards for a “good society” at cotillion. Sporting practices in the 19th century, while having strong economic implications, also represented who in society had access to leisure activities and entertainment – white, upper-class folks. Equestrian gymnastics, a slightly enhanced version of horse racing, functioned as performances for the New Orleans community in which horse exchanges were made in partnership with the local theatre. It mostly consisted of vaulting and specific acrobatic moves – on a moving horse.

Announcement of equestrian gymnastics from the Times-Picayune archives, January 1841

Both ballroom dancing and equestrian gymnastics reinforced the social implications of sporting events in the mid-19th century, specifically highlighting the exclusion of Blacks and the elevated importance of the upper-class. The physicality of the two sports was ignored in pursuit of the entertainment it represented for the more valued members of society, reflecting the larger treatment of Blacks in sports throughout the nineteenth century.

NOLAbeings

Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings

Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

Data corner: Adobe Suite (create a PDF, social media graphic, presentation, edit a photo and video

Data corner is where you go to work with analytics and top tech skills. It takes on everything from PERL and SQL to Canva and Sprout Social.

Data corner: Adobe Suite (create a PDF, social media graphic, presentation, edit a photo and video

Data corner is where you go to work with analytics and top tech skills. It takes on everything from PERL and SQL to Canva and Sprout Social.