Gibran Hassan and Hannah Nabavi after winning the MLK Invitational Tournament

2020

8:50am

His fingers gingerly untangle a dusty extension cord, releasing every last inch necessary to string it from the outlet in his family’s living room to his workspace for the day. He’s been relegated to the garage while his younger siblings attend their Zoom classes. Six months ago, Gibran Hassan was a freshman hustling around UCLA’s campus, finally free from his childhood bedroom and the sleepy streets of Santa Rosa, California. But the pandemic has brought him here again, sharing the walls with his devout parents and his restless siblings. It’s also brought him back to the Golden Gate Speech and Debate Association’s season opener tournament, but this time digitally, as a hired judge rather than a participant. His setup is relatively the same— crisp sheets of legal paper, a whirring laptop, his preferred brand of multicolor pens, a massive cup of coffee—but the drafty garage lacks the pomp of a hotel ballroom.

2019

8:50pm

A solemn agitation hangs in the ballroom at the Renaissance Chicago North Shore Hotel. As the clock draws closer toward 9pm, the shrill beeping of kitchen timers setting their count picks up its frequency like a pulsing heart monitor. Hannah Nabavi, a junior at Sonoma Academy, rises from her seat on the stage to address the eager crowd. It’s one of the final elimination rounds in the National Debate Coaches Association’s National Championship, and Gibran and his partner are up against the highest ranked team at the tournament, Giorgio Rabbini and Nick Mancini from North Broward Preparatory School. Hundreds of teenagers from across the country gather around the centerfold. They’ve barely slept in the past 72 hours, their eyes burning from exhaustion and the constant light of their laptop screens, but still chatter excitedly through their hoarse voices as they prepare to witness the conclusion of another grueling tournament season. “Before I start, I’d like to say a couple thank you-s…” Hannah begins. “Gibran, I can’t believe this will be my last debate with you,” she chokes up, “You’re going to do great at UCLA.”

2020

11am

Gibran spent all yesterday updating his paradigm, his judging philosophy posted publicly on the tournament organization platform Tabroom. He discloses his unfamiliarity with complex Kritiks, arguments which invoke the dense philosophies of everyone from Jacques Lacan to Jean Baudrillard, and expresses his love for highly technical legislation-driven rounds, referencing his own career when he writes, “it’s still one of my favorites.” There aren’t any requirements, yet his complete paradigm is over one-thousand words. Each section dives into the nerdiest depths of his reflections on the activity, dancing around the desire to tell stories about the good old days. But where he puts the nostalgia aside, he reveals a soft spot for the next generation. “Do what you do best,” he writes, “Please let me know if there is anything I can do to make the debate more accessible for you.”

2019

11pm

Gibran and Hannah have three minutes of their allotted in-round prep time left to write the final speech. They scour the massive Dropbox they’ve spent all year compiling, filled with terabytes of documents, each of which can be over twenty-thousand words long. The documents contain thousands of excepts from scholarly papers and dense academic books which they use as evidence during their rounds. Each night after Gibran completed his normal high school coursework, he’d spend twice as many hours researching and organizing his folders, gaining an intimate familiarity with the vast reserves of information which allows him to navigate the files seamlessly.

Each summer he’d get a head start on his research, attending debate camps held by some of the most prestigious universities in the United States, where he spent nearly twelve hours a day researching, performing speed speaking drills, and competing in practice rounds. These programs last for up to nine weeks, and while his friends went on family vacations or got summer jobs, he spent his summers in college dorms reading material most undergraduates haven’t even encountered. As Gibran glances into the crowd, he recognizes the faces of his camp friends, eager and slightly envious amongst the droves of spectators.

He frantically looks for the last piece of evidence he needs. He moves to his folder from camp with only 30 seconds left, clicking through the tabs quick as lightning. Courts are key to ensure equal access to education for children – Lipshutz 14. Bingo. He instantly sends the text to the speech document, using his handy debate software Verbatim, right as the timer goes off. “Sending out the speech doc,” he says as he moves to the podium.

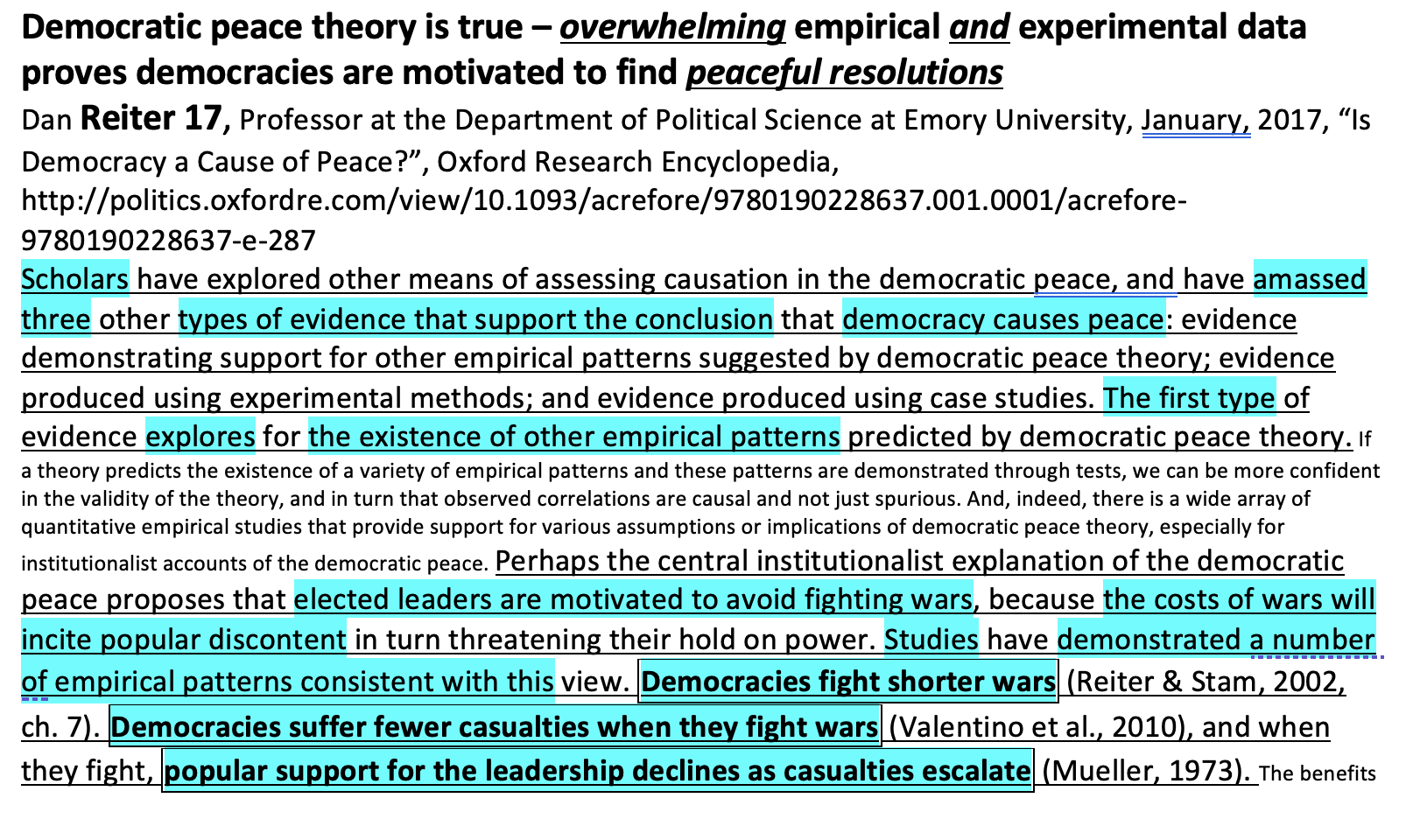

An example of a piece of evidence read aloud in a policy debate round

He stands and rolls his shoulders back in preparation for the last speech of the round, and of his career. He starts the timer, and suddenly he is speaking at nearly 350 words-per-minute, a speed which is completely indecipherable to an untrained ear. “US commitment to a right to education is a prerequisite to effective democracy promotion efforts! the plan galvanizes international democratic consolidation,” he booms, “That’s Lerum 5!” The full steam of his sermon picks up as he delves into the intricate details of electoral politics and how the affirmative’s plan will initiate a doomsday scenario.

“The US must articulate and promote a strong commitment to education as a way to promote democracies that are sovereign and stable. The time is ripe for the United States to align its domestic priorities with those it promotes throughout the world!”

He bounces his hand gripping the timer, a metronome pacing the barrage of speech.

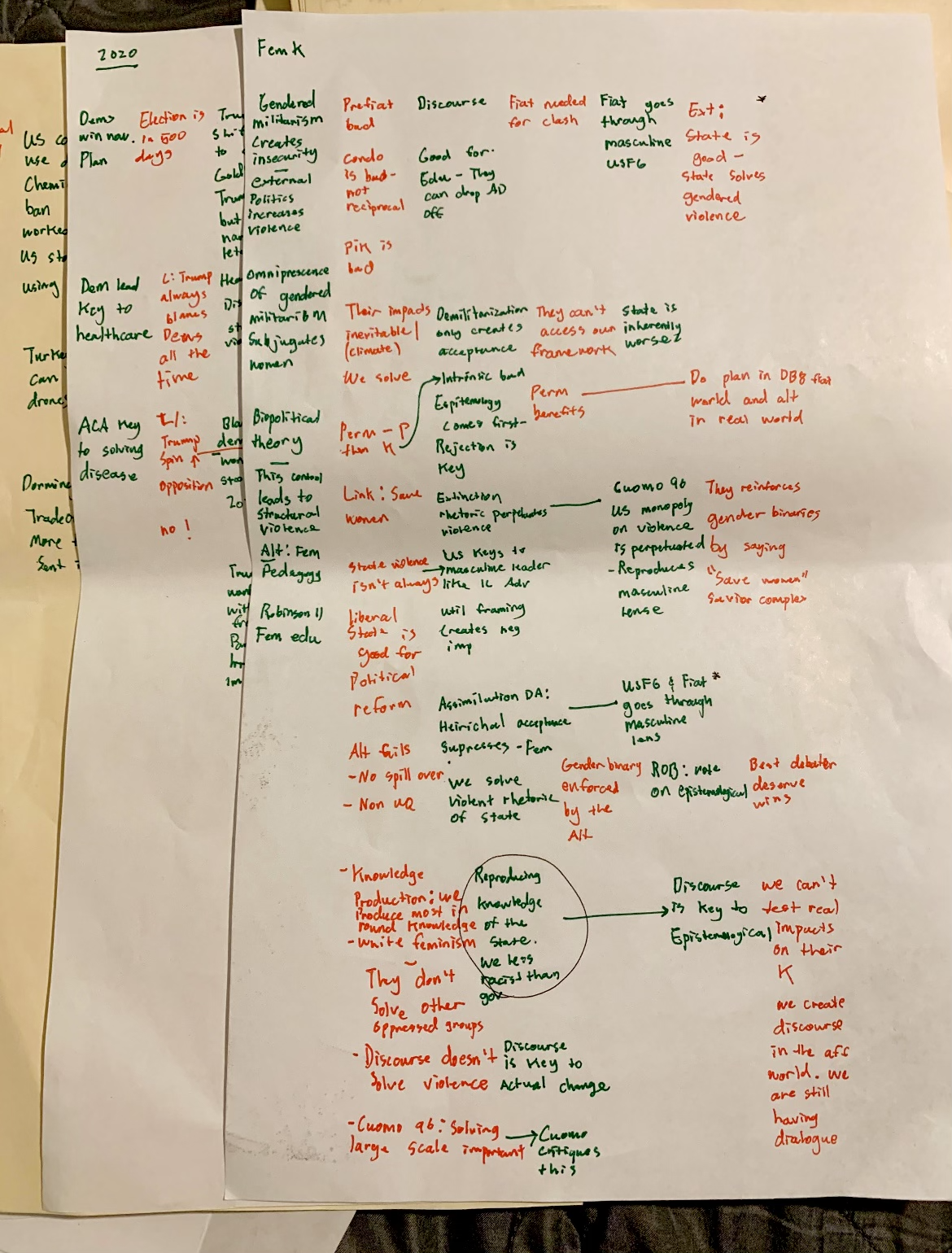

Each pause for breath is punctuated by the crowd’s furious scribbling as they try to capture every argument on their “flow”. “Next, Topicality: interpretation:” cries Gibran, and the sheets of paper ruffle as the crowd turns to that page of notes. “Default to competing interpretations – their interp ruins any affirmative ground, our standards maintain competitive reasonability and prevent neg in-round abuse,” he says, a cacophony of pens clicking as they scratch Gibran’s contention next to his opponents’, using intricate shorthand to keep up with his breakneck speed.

An example of a “flowsheet”, the specialized note taking systems debaters use to keep track of arguments made in the round

While the uninitiated may expect debate to be an exercise in eloquence and oration, the activity has morphed into a game of verbal chess, with each team deploying as many arguments as possible within the rigid time constraints in the hopes their opponent misses a point of attack. If Gibran forgets to answer even a single piece of the other team’s claims, it could cost him the round, and as he speaks he flips through his meticulous flow sheets, telling the judges and spectators exactly where to put ink to page. When he really hits his stride, his speed combined with the ultra-specific lingo gives him the ability to fully rebut a contention in mere seconds, leaving him enough time to build more offense. Every spare second is used to overwhelm the other team as he dumps arguments on the flow, and as the timer ticks away his frenzy builds, the barrage of speech only punctuated by shrieking gulps of air.

2020

11:50am

Gibran Hassan: “And for those reasons, my ballot goes to the affirmative team”

2019

11:50pm

Mike Shackelford (Judge): “Congratulations to the affirmative team who will advance to the next round, North Broward Mancini and Rabbini. And congratulations to Sonoma Academy’s Nabavi and Hassan for making it this far in the elimination rounds at the National Championship.”

They stand from the podium to shake their opponents’ hands. Gibran returns to his seat to pack up his laptop. It’s time to go home.

Rabbini and his partner advanced through the elimination rounds and won the National Championship. He has since won many more tournaments while debating at the collegiate level for the University of Michigan.

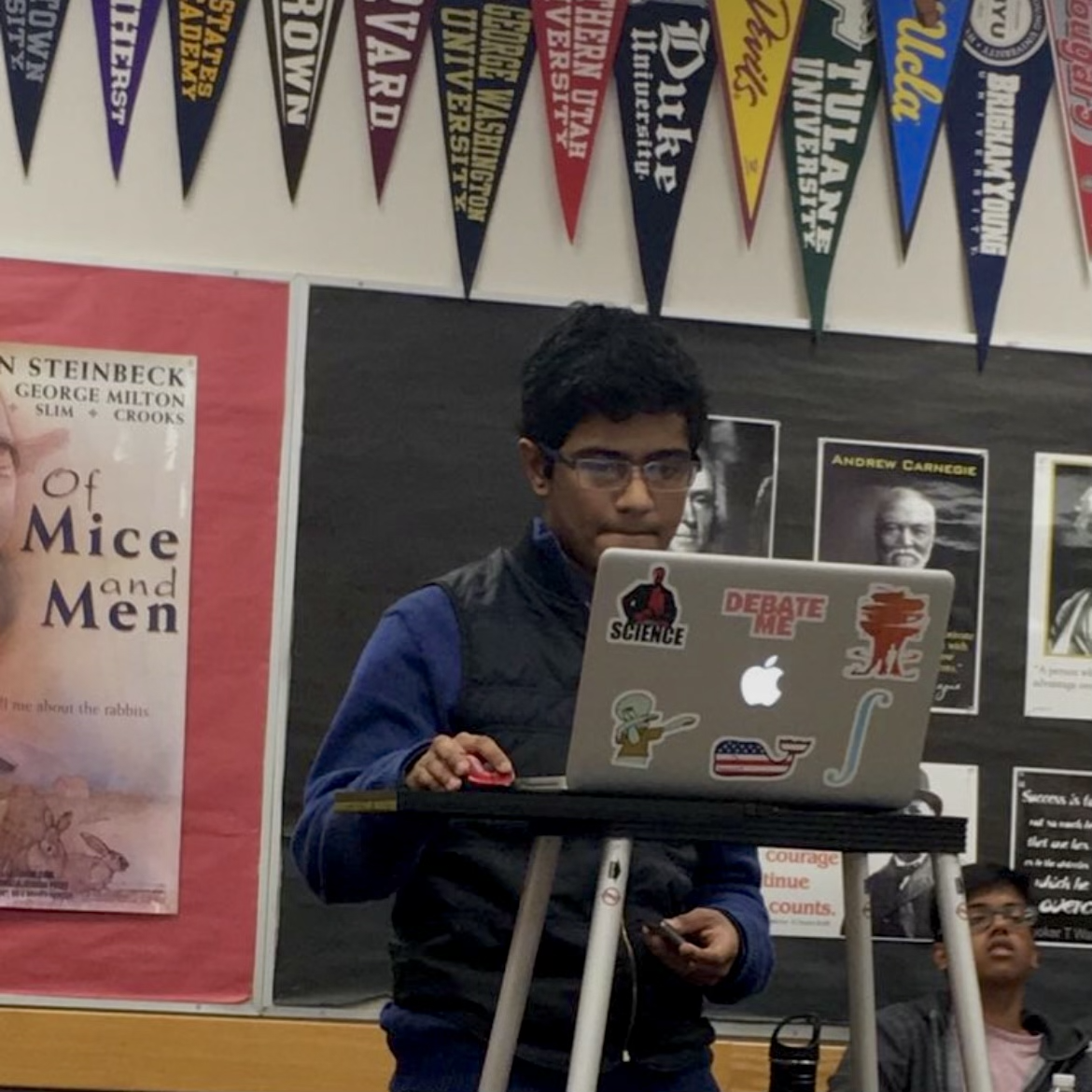

A debater prepares his speech. Laptop stickers are a key part of community culture.

2020

12pm

The first round he judges is a slog. The novice team stumbles through the case their coach prepared. Gibran scrolls through his Twitter feed for most of the round. After submitting his ballot, he joins the Google Hangout room with his former teammates who were also hired to judge, where they discuss results and the most promising teams this season. The conversation is peppered with the jargon they’ve learned to tuck away around their other friends. The banter turns to the blunders made by the young debaters. “Were we really that bad when we started?” chuckles Hannah, his old partner. “Hannah, remember when you called the speaker of the house John Boner?” Gibran retorts. The conclusion amongst the group: yes, we were that bad.

Pictured: Gibran Hassan (left)

2019

8am the next morning

Gibran steps into the van with his teammates, throwing his heaving backpack on the crumb covered floor. Hannah taps him on the shoulder, “I just wish they went for politics and states counterplan in the block,” she says, “you know, make debate great again!” The van erupts in delirious laughter, dazed from sleep deprivation and over-caffeination.

“The States CP is the British showing up to the American Revolution in the DEATH STAR,” teammate Emily says through choking laughs. As they debrief the weekend, Gibran jokes along, though he’s in a melancholier mood than the rest of the squad.

He stares at the falling snow through the frosted window, and it finally hits him that this will be the last exhaustion-crazed van ride he’ll have with the team. They’ve spent countless hours throughout the school year travelling together, without their friends or family, devoting themselves to the same research, and sharing the same esoteric language. He feels a pang of grief as he realizes he must say goodbye to that camaraderie upon his impending graduation, but an even sharper twinge when he realizes there’s nothing left to do: no more research to compile, no more speaking exercises to drill, and no more victories to be won.

Much has been said about the identity crises of student athletes, who spend their entire lives training their bodies for their sport, only to bid it farewell and enter the ‘real world’ upon graduating. Some might go on to become coaches, or play in the big leagues, and some may simply move onto other things, fondly remembering the days when they were a champion. The same goes for policy debate, but these teens’ legacies are confined to the few privy to their intense and isolated world. As with competitive sports, the most talented and devoted go on to debate at the collegiate level, like Rabbini, delaying their retirement temporarily. Some use their skills to work towards other goals, like Hannah, who’s pursuing a career in public policy while studying at UC Berkeley. And some, like Gibran, return to what they love by teaching the next generation.

NOLAbeings

Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings

Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

Data corner: Adobe Suite (create a PDF, social media graphic, presentation, edit a photo and video

Data corner is where you go to work with analytics and top tech skills. It takes on everything from PERL and SQL to Canva and Sprout Social.

Data corner: Adobe Suite (create a PDF, social media graphic, presentation, edit a photo and video

Data corner is where you go to work with analytics and top tech skills. It takes on everything from PERL and SQL to Canva and Sprout Social.