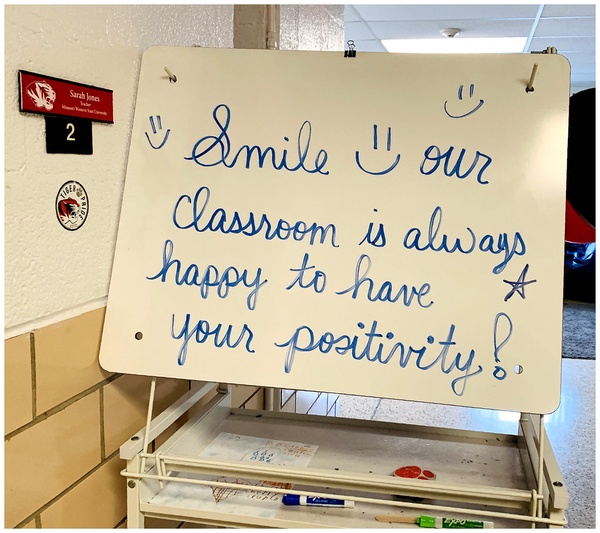

We talk about being positive in school, but how do we foster a positive environment? (Photo: Creative Commons)

The school’s professional culture* was reeling. Staff turnover was high and morale was low. Several teachers actually described the work environment as “toxic”.

When I asked the principal what she was doing to address the issue(s), she perked up and exclaimed, “Shout-outs! We do them at our faculty meetings. It’s a great way to build self-esteem.”

“I agree,” I said. “Tell me more.”

“Well,” she said, “we have a bulletin board in the conference room. Throughout the week, teachers post shout-out cards. I read them at the end of our faculty meetings. Then, I put them in a basket, and draw a winner. The person who received the shout-out, and the person who gave it, get a longer lunch period the following week. It’s a great way to incentivize the practice, don’t you agree?”

“I see,” I said.

Just minutes before the next faculty meeting, I watched as teachers frantically filled out cards and posted them to the board. It was like the rush to buy lotto tickets just before the Mega Millions drawing. Hastily scribbled, they read, “To Lisa for being a rock star! To Melissa for helping me out of a jam! To John for covering my class! To everybody for everything!!!”

After seeing this, I became skeptical that shout-outs, especially in this form, were the panacea the principal was hoping for…

Snaps and Claps

When I was a student in school (so long ago that chalk was still the predominant technology), the closest thing to a shout-out was a mascot sticker on the back of football helmet, or a cum laude certificate at the end of the year.

As a teacher, I never really heard the term either. My principal was happy when classroom doors were shut, the halls were quiet, and no one, especially parents, complained.

It wasn’t until I got involved in education reform that the term gurgled…no, gushed to the surface. In post-Katrina New Orleans Charter schools, shout-outs were divvied out like Mardi Gras throws on Fat Tuesday. They were about as common a practice as teachers naming their classrooms after their alma mater, and referring to their students as “scholars”. Snaps and claps could be heard everywhere.

Shout-outs are the baby aspirin of school improvement initiatives. They are relatively benign. They are much easier than making “data-driven decisions” or mapping out the curriculum; they can be an effective way to promote “best practice”; they don’t cost anything; they are rarely controversial; and, they generally make people feel good. What’s not to like?

Not much. But, as with all school improvement initiatives, there is always room for caution.

For example, the impact of shout-outs can be diluted from overuse. I once knew a principal who stuffed them into every email and text; and, on Fridays, he read out a laundry list over the intercom that stretched from here to Zaire. Many of the teachers got so annoyed, they simply taught through/over his droning.

If shout-outs are not done in an equitable or diplomatic way, they can also sometimes hurt feelings or even sew division. Recognizing the same teacher again and again can lead to accusations of that teacher being a principal’s pet; and forgetting another might just lead to a coup.

Without faculty buy-in, shout-outs can quickly become and exercise in futility. As we all know, a disingenuous compliment is no compliment at all.

And, finally, I’m a big fan of the gospel of intrinsic rewards and the high-brow notion of “learning for learning’s sake”. (Yes, I know I’m a dreamer.) As a teacher, I was influenced by books by Alfie Kohn like Punished by Rewards and Schooling Beyond Measure. If we are constantly patting ourselves on the back, we sometimes lose focus on the real prize, excellence. Shout-outs become the currency of a token economy – for teachers. We end up doing good to be caught doing good. To quote C.S. Lewis, “Integrity is doing the right thing even when no one is watching.” When you have that, chances are, your school culture is in a really good place.

The circle of life applies to how we educate ourselves and others. (Photo: Creative Commons)

The Circle

A colleague of mine “borrowed” an idea for organizing group meetings from a school in Boulder, Colorado. He shared it with me, and I immediately stole it for my school. It’s called The Circle, and it goes something like this:

For me, The Circle is the perfect platform for sharing shout-outs. It’s intimate and honest. It builds trust, and it promotes mutual respect. And, it provides just the right amount of caution.

* Professional culture is one of the most important and complicated aspects of any school. It’s influenced by a myriad of factors, from ineffective leadership and a preponderance of naysayers, to poorly implemented policies or a focus on compliance rather than excellence. Once gone bad, it’s difficult, if not impossible to turn around. And, obviously, it can’t be salvaged by a single initiative.

A good start is to conduct a cultural survey. At least that way, you know what you are up against.

Folwell Dunbar is an educator and writer from New Orleans. He runs a small school for children and adults with autism. When he’s not busy giving shout-outs, he can be reached at fldunbar@icloud.com.

NOLAbeings

Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings

Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

Data corner: Adobe Suite (create a PDF, social media graphic, presentation, edit a photo and video

Data corner is where you go to work with analytics and top tech skills. It takes on everything from PERL and SQL to Canva and Sprout Social.

Data corner: Adobe Suite (create a PDF, social media graphic, presentation, edit a photo and video

Data corner is where you go to work with analytics and top tech skills. It takes on everything from PERL and SQL to Canva and Sprout Social.