Editor’s Note: You didn’t think we’d have a “Holiday Hot Topics” series without bringing up sex, did you? Well, if you did, shame on you (and not on sex workers). Here, writer Jessica Rice looks into the decriminlization of sex work and why that hasn’t come to New Orleans. We suggest having this conversation with grandma around; it adds for a whole other level of conversation.

It’s difficult to imagine that there is any corner of the world where sex work (SW) has not taken place and still, the critical dialogue that is pervasive in many cultural spaces is saturated in moralism. There are, however, a select few locales that exemplify the way in which the regulation and decriminalization of SW can prove mutually beneficial to all parties involved, the most well-known of which is undoubtedly Amsterdam, the Netherlands.

Sex Worker in Amsterdam’s Red Light district.

Photo by: Jean Pierre Jeanmin

Known as a hub for SW as early as the 16th century, the cultural impact of this line of work is deeply entrenched in the history of the city. After undergoing a period of extreme prohibition led by Christian countermovement in the 1800s, the latter half of the 20th century was characterized by a resurgence of SW and brothels as the global sex tourism industry grew in popularity. While the brothel ban of the prohibition era was still technically ratified until 2000, mid 20th century policy at a local level condoned and tolerated prostitution; this policy was coined Gedoogbeleid. An inherently Dutch concept, there exists no direct translation for the policy itself or the verb, “Gedoegen” that it is derived from. The most accurate approximation of “gedoegen” in English is, “to tolerate”, however that translation incorrectly suggests a degree of passivity whereas the Dutch term refers to the active practice of pragmatic tolerance. In the context of governmental policy, Gedoogbeleid is utilized in reference to social issues that are discussed until consensus is reached; if a concrete solution is unable to be reached, the behavior is accommodated and tolerated by law enforcement as long as it exists within designated parameters.

Gedoogcultuur, defined most closely as the culture of permissiveness born out of gedoegen, rose to prevalence tangentially with the counterculture movements of the 1960s and early 1970s and eventually led to the formalization of the Dutch polder model of consensus-based decision making in the 1980s. Until 2000, Dutch policy on SW acknowledged both its legality and illegality but maintained the consensus against its criminalization for the purpose of harm-reduction. On Oct. 1, 2000, SW in the Netherlands officially departed from its half-legal status of toleration and became a fully legal and licensed field of work, finally lifting the century-long ban on brothels.

With well over 20,000 SWs in the Netherlands, 40% of whom work within the city of Amsterdam, the legalization of SW has meant the integration of prostitutes into the labor market as tax-paying citizens. While SWs are required to contribute to their federal and local economies through their income, they are oftentimes denied the right to open bank accounts with local branches because of occupation-based discrimination. Amongst SW’s in the Netherlands, 60% say they were subjected to physical violence as a result of stigmas surrounding their work, 78% reported sexual violence, 93% reported emotional violence, and 58% reported financial-economic violence all as a result of stigma surrounding Sex Work. 97% of Dutch SWs in total reported that one or more incident of stigma-based violence occurred to them in the 12 months prior to being interviewed in a 2017 study.

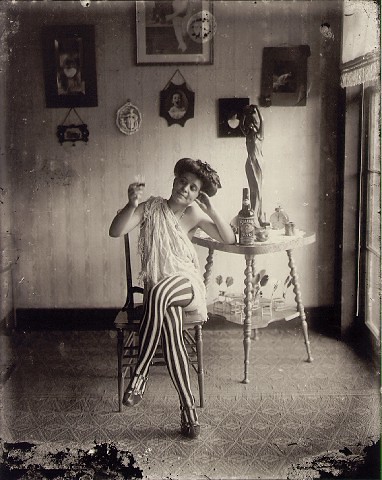

In New Orleans, SW served as the foundation for the birth of the jazz musical culture in Storyville, the red-light district of the city in the early 1900s. Deeply entrenched within the history of jazz and one of the oldest forms of entertainment, SW is a part of the cultural framework of the city of New Orleans.

Storyville Prositute, 1917

Photo By: Ernest Bellocq

In order to effectively evaluate any aspect of SW as it exists within New Orleans, we must first deconstruct the foundations of our general perception. The ways in which western culture conceives of SW is rooted deeply within a normative white heterosexual male construction of femininity, as is made evident by the fact that each of the major players in the legislative efforts against SW are white and male. Consider, that SW is a field predominantly dominated by women in a city that nearly 60% black.

There are two tactics generally utilized to enact policies that directly affect SW: fear and intimidation tactics through law enforcement and legislation that criminalized the solicitation of sex for work. In January of 2018, came the first strip club raids that combined the efforts of the New Orleans Police Department (NOPD) and the Louisiana Office of Alcohol and Tobacco Control (ATC.) NOPD reported that the raids of strip clubs, which frequently operate as the physical workspaces for SW, were necessitated because they operated as fronts for human trafficking, though these claims were made with no evidential basis. Months prior to these highly publicized raids, NOPD made a habit of working undercover within strip clubs in order to itemize sexual conduct, as harmless as SWs touching their own bodies, and reported such behavior as being outside of the parameters of accordance with liquor licensing. These reported Alcohol and tobacco violations would result in notices of suspension from the ATC and were used to bolster the accusations against strip clubs during the raids, though no correlation between the two existed. Just weeks later, towards the end of January, eight different strip clubs were raided by ATC agents and NOPD officers in the middle of their business hours, harassing and questioning the SWs without any explanation. In a press conference that was released later that month, Louisiana ATC Commissioner, Juana-Marine Lombard openly admitted that no arrests relating to sex trafficking had been made as a result of the raids, essentially rendering the entire operation null. What was effectively launched however, was the “Unemployment March” a movement of resistance spearheaded by the SWs and dancers alike that had been grouped together by false claims of criminality and had been left unemployed by the raids and consequent closures of their spaces of work. The messages of the SW community were communicated on the signs they carried and resounded throughout the city and the media:

“Your political agenda shouldn’t cost me my future,” “I am not a victim! I do not want to be saved!” “Strippers’ rights are human rights.”

Riding off the backs of the decentralization of SWs in the quarter due to temporary closures of strip clubs, city council members-imposed moratoriums that proposed and passed zoning ordinances that disallowed more than twelve strip club venues to be open for operation simultaneously. Given that these clubs are only permitted legally within the French Quarter, SWs are already required to exist within the delineations set by white male lawmakers; those SWs that hail from peripheral areas and are members of marginalized groups are automatically made more vulnerable by legislation that determines the legality of their profession based on the ability of these workers to meet appropriate “standards” that are often racialized and heteronormative. While the city zoning ordinances were struck down in March of 2018, signifying a victory for SWs against infrastructural attempts to decentralize clubs in order to make them more “family friendly,” there is continual support for legislation that inflicts direct stigma-based violence in the form of financial harm. HB 830 and SB 335, both of which assume automatic linkage to sex trafficking amongst SWs, exemplify moralist policy objectives motivated by ulterior motives, which are in this case are commercial tourist infrastructural investments that necessitate the continued gentrification and forced peripheral movement of “lewd” business.

Big Daddy’s Strip Club in the Quarter

Photo By: CCSearch

The striking irony of it all is that moralistic legislation passed to “protect” SWs from sex trafficking inherently puts them in more acute danger and invites stigma-based violence in a plethora of ways: 1) SWs engaging in survival sex work are put at greater risk with the least amount of protections in place especially if fined monetarily 2) POCs and LGBTQ+ SWs are also found guilty of SW crimes at disproportionately high rates and face predatory policing patterns, along with unequal prosecution & sentencing 3) SWs that can no longer find work within a legal workspace are far more likely to be forced into unregulated work that makes them highly exploitable to figures like pimps that deny their autonomy.

NOLAbeings

Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings

Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

Data corner: Adobe Suite (create a PDF, social media graphic, presentation, edit a photo and video

Data corner is where you go to work with analytics and top tech skills. It takes on everything from PERL and SQL to Canva and Sprout Social.

Data corner: Adobe Suite (create a PDF, social media graphic, presentation, edit a photo and video

Data corner is where you go to work with analytics and top tech skills. It takes on everything from PERL and SQL to Canva and Sprout Social.