I’m approaching the intersection of South Carrollton and South Claiborne when I see an elderly woman standing in the median. She’s holding a cardboard Pizza Hut box with the words “Homeless, Hungry, Anything Helps” scribbled on the brown, grease-spotted interior. I recognize her from the day before.

While cars idle at the traffic light, she walks up and down the grassy median attempting to make eye contact with drivers. Now— if you’re like me, you are trying your best to look straight ahead, to avoid making a connection, to avoid feeling any guilt. Then I watch as a man’s arm pokes out from the car in front of me, extending a one dollar bill to the woman. “God bless you sir!!” she says and continues down the aisle of vehicles.

Of course this wasn’t the first time that I’ve seen someone hand over money or food to a person standing in the streets, but something made me feel differently that day. All of a sudden, I was ridden with that same guilt I was trying to avoid in the first place. After watching someone else so mindlessly extend a helping hand to a stranger, I wondered– am I part of the problem? I began to ask myself why I felt so hesitant to help her, or any homeless panhandler for that matter. I think that the issue lies in our subconscious combination of those two words, homeless and panhandler.

Panhandling has been an issue in New Orleans for far too long. Long-time residents and visitors alike are growing increasingly unhappy and uncomfortable based on their own negative encounters. In a Tripadvisor review from 2016, one man wrote that Bourbon Street was “just ok” and “would be so much better if there was control over the amount of homeless or drunks begging for money, cigarettes, etc.” This is not the type of review that the city of New Orleans — a place that heavily relies on the tourism industry (pre-Covid) — wants to receive. A review like this, especially if it comes from a user who is well regarded across the Tripadvisor community, could affect others’ decision to visit Bourbon Street, or to travel to New Orleans at all.

In his article “Dealing With Panhandlers,” Chris Rose quotes former Director of Homeless Policy for The City of New Orleans, Stacy Koch. Regarding panhandling, she states: “It makes the public really angry … because every time they stop at a corner, someone is banging on their window asking for money. It creates a total lack of empathy and sympathy for the homeless” (3). While the majority of sign flyers and panhandlers are polite and unassuming, there are the few that beg in an aggressive manner, or react strongly when someone says no. Experiences like this can leave a sour taste in anyone’s mouth.

This is seen in reality every day. Another example of this can be seen in the comments of an article posted on SPL!NTER, in which a writer has interviewed different homeless people throughout New Orleans. One comment reads: “If you ask any bum on the street, they’re ALL veterans. Every one of em.” What the woman who wrote this comment is tapping into here is the issue of trust. The same way that aggressive panhandling perpetuates a lack of empathy for homeless people, because there are a few who are dishonest, there is an assumption that much of what is written on everybody’s cardboard signs is a lie.

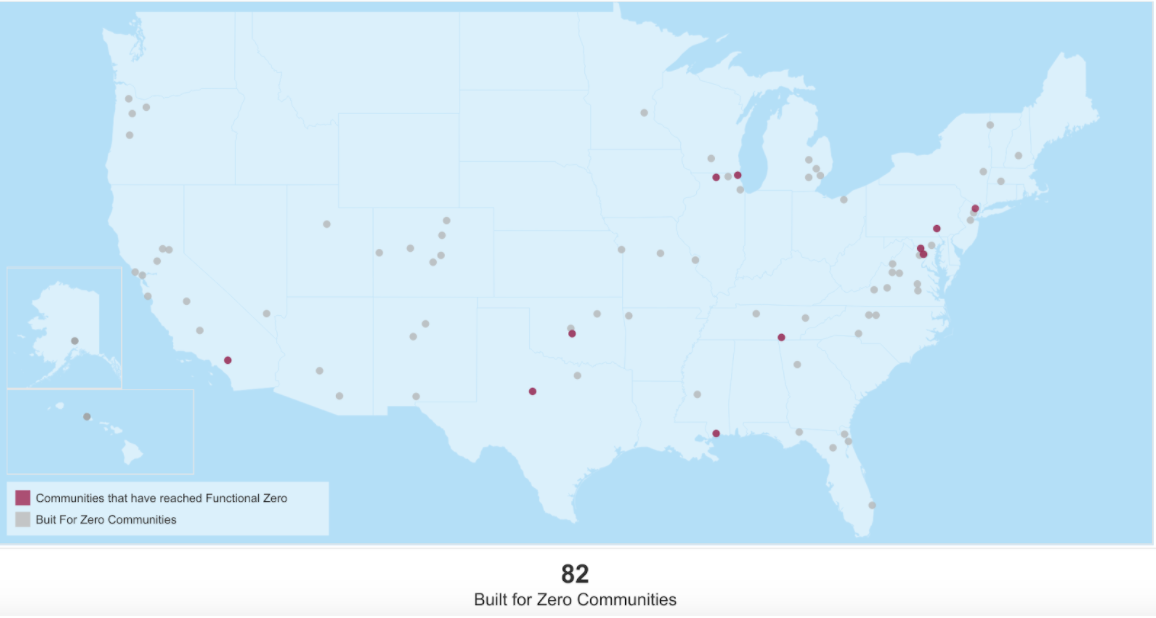

This doesn’t have to be New Orleans’ reality. Throughout my research, I came across a non-profit organization called Community Solutions that has developed a specific and unique program to help combat homelessness across the United States. The program is called Built For Zero and it is “a movement of more than 80 cities and counties using data to radically change how they work and the impact they can achieve” (1). Since their start in 2013, Built for Zero has helped eleven communities to end veteran homelessness and three communities to end chronic homelessness, with Bergen County, NJ and Rockford, IL succeeding in both.

On their webpage, they provide an in-depth case study of how they achieved success– or as they call it, functional zero– in ending veteran homelessness just recently (January 2020) in Chattanooga, TN. The organization explains the three major steps that they tok in order to make this possible. The first was, “building a unified regional team”, sometimes called the “command center,” the second was “using real-time and person-specific data”, and the final one was “testing new improvements to their system”. In simpler words, this means: gathering a reliable and dedicated group of people, getting to know everyone on a first name basis, and not being afraid to adjust their plans to fit the needs of Chattanooga on an individual level.

The reason why Built For Zero’s program is working for so many communities is because their solutions are based on the individual rather than the blanketing concept of “the homeless.” The organization explains how in most cases, success in solving homelessness is based on how much good any singular housing agency has done and “not on whether a community collectively reduces homelessness” (1). The volunteers working with Built For Zero create a list with every homeless person’s name in the city. They pride themselves on collecting “comprehensive, real-time, by-name data,” rather than an annual census of the homeless population.

Below is an image that is posted on Community Solutions’ webpage.

The red dots on the map represent the communities that have reached ‘Functional Zero’, a place where homelessness is considered rare (and brief when it does occur). The grey dots show the various communities where Built For Zero has implemented their practices. I was genuinely surprised to see that New Orleans was not on this list– or any city in the entire state of Louisiana for that matter. Community Solutions’ Built For Zero project would thrive in a city like New Orleans for numerous reasons. Anyone who has lived in New Orleans for some period of time knows that the people of this city possess something extra-special to them. There isn’t a word in the English dictionary that describes this ‘something,’ so we’ll call it ‘sprickel’– that intangible and inexplicable positive aura that surrounds a native New Orleanian. Because of the sprickel that is innately built-in to New Orleanians’ souls, Built For Zero’s methodology of collecting real-time and real-name data would work flawlessly.

Learning the names of the homeless population in New Orleans brings a person one step closer to the issue, and allows that individual to literally check-off names as they worked with the community to solve this crisis. The woman standing in the median is no longer an untrustworthy panhandler but instead becomes maybe ‘Casey Brown’ who lost her home in a fire last year. Built For Zero’s strategies combat homelessness and sign flying simultaneously. If more community members were aware of the homeless population on a first name basis, it would eliminate so much uncertainty and nervousness when handing over a five dollar bill to someone standing in the street.

NOLAbeings

Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings

Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

Data corner: Adobe Suite (create a PDF, social media graphic, presentation, edit a photo and video

Data corner is where you go to work with analytics and top tech skills. It takes on everything from PERL and SQL to Canva and Sprout Social.

Data corner: Adobe Suite (create a PDF, social media graphic, presentation, edit a photo and video

Data corner is where you go to work with analytics and top tech skills. It takes on everything from PERL and SQL to Canva and Sprout Social.