Editor’s Note: According to a History of New Orleans Voodoo, “The core belief of New Orleans Voodoo is that one God does not interfere in daily lives, but that spirits do. Connection with these spirits can be obtained through various rituals such as dance, music, chanting, and snakes,” and in this way the mystery associated with New Orleans begins to materialize. However, it is important to know the truth behind these myths in order to honor the history of the city and to adequately move in the right direction in the fight for social and environmental justice. From its history and culture, all the way to its arts and food, the tourism industry in New Orleans has perpetuated a vast array of myths which continue to exploit the city. Yet, while New Orleans is so popular and well known, the question remains: how much of what people know is actually true, and how does this impact the city? Through exploring New Orleans’ Senegalese roots, highlighting its Honduran connections, and uncovering the origins of hip hop, the following articles provide a keen insight into the various ways the tourism industry in New Orleans continues to spread disinformation for monetary gain.This piece was originally published on June 23, 2020.

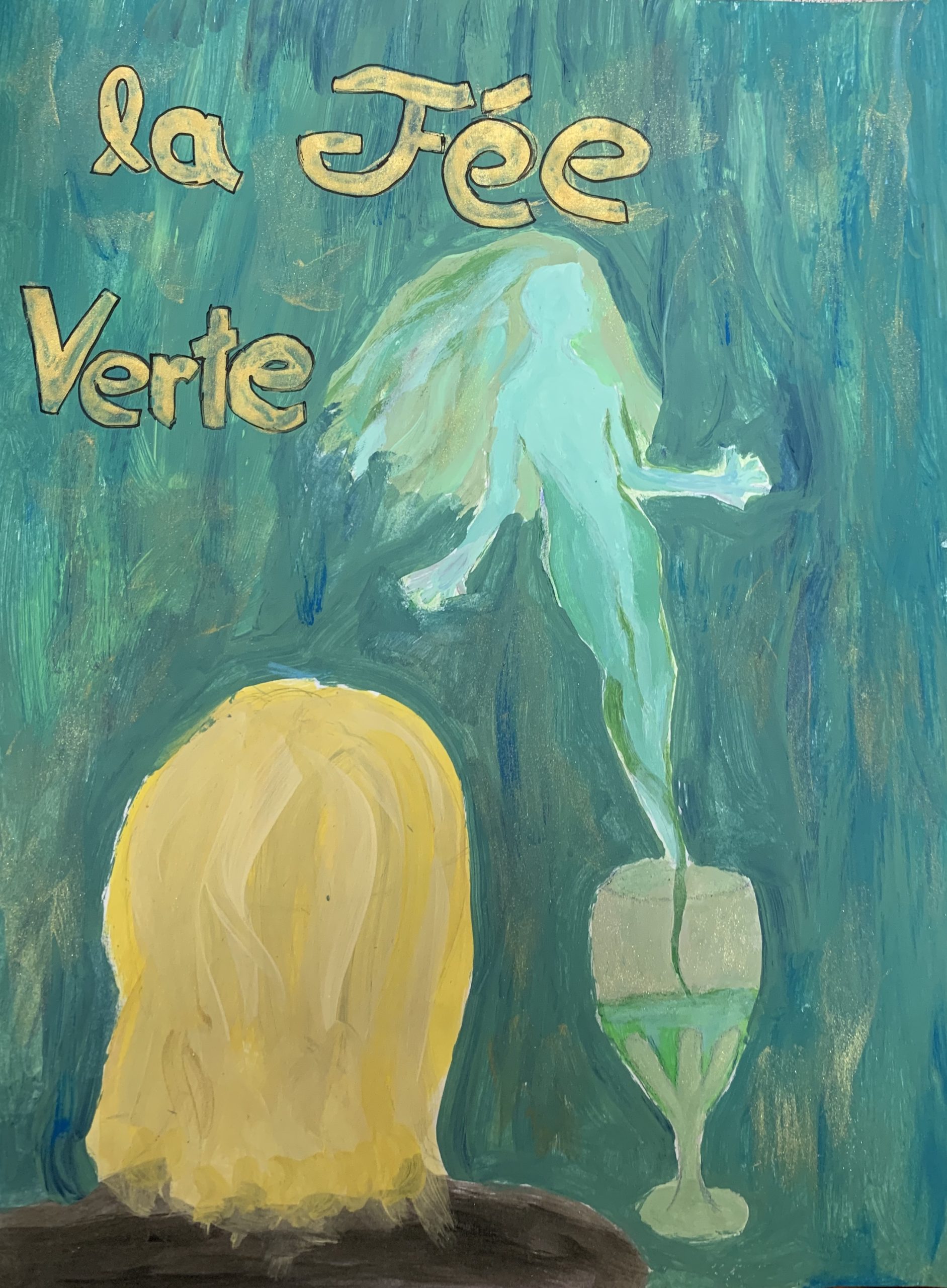

painting by Krista Andreoni

Jean Lafitte’s Old Absinthe House (Photo by: Krista Andreoni)

As I squeezed past the crowd at the historic Old Absinthe House bar the door, I could see no obvious sign that the worn down leather on the chairs had once held the backsides of prominent figures throughout history. Perhaps they had changed seats in the past 200 years. Currently, the barstools were occupied mostly by adults in their 30s or 40s along with an elderly couple and me, a young girl in my early 20s.

The Old Absinthe House began selling the mystical drink in the early 19th century (6). I saw the menus advertise the bar’s low prices, enticing people across all social classes to come inside. Among the famous patrons of the Old Absinthe House are Mark Twain, Oscan Wilde, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, and Frank Sinatra (6). The visits from these prominent figures contributed to the bar’s allure. I overheard a patron order a drink called Sazerac. This is considered to be the first absinthe cocktail, originating before the Civil War, and the Old Absinthe House is credited with its invention (4). In 2008 the Louisiana Legislature proclaimed Sazerac as the official cocktail of New Orleans (4). This contributes to the mythology by ensuring that the cocktail is documented as a pivotal component of the city’s history.

Beyond this drink order, other snippets of conversations that I overheard revealed that most people in the bar were sharing stories with one another. The doors of the Old Absinthe House were wide open, and a mass of people were pressed from the inside of the walls out to Bourbon Street. Outside, people were gathered around jazz musicians. That, combined with the bar’s own music, made it too loud to clearly hear conversations. The bombardment of sounds divided my attention, but I seemed to be the only one distracted. All the other patrons inside the Old Absinthe House were focused solely on their companions. Absinthe is rumored to have hallucinogenic effects, but that myth has been debunked (1). Other customers of the Old Absinthe House seemed unbothered by the jazz band three feet away. Perhaps this shows that they were able to stay focused and hold a conversation, giving more credience towards absinthe being non-hallucinogenic. Alternatively, it is possible that the patrons were deeply engrossed in their discussions because they wanted to share the “shady clarity” (5) that absinthe had revealed to them.

The people around me were drinking alcohol that had numerous myths surrounding its dangerously addictive qualities of providing drinkers with inner peace. The first book to place absinthe central to the plot was Octave Féré and Jules Cauvain’s The Absinthe Drinker (1865) (2). This book warns readers of the dangers of absinthe by following the crimes of two lovers addicted to the drink. The woman in the book derived an unholy power from the beverage:

the green fairy gives them an almost unlimited power over men, as well as an irresistibly attractive vampire physique: Whenever we had to drink, it was absinthe that this frenzied creature demanded, and each time her goddess forehead lit up with a marvelous radiance, her eyes flash brighter, her speech became more vibrant, more acute, it had a hellish spirit (1).

The book ends with the man being brutally murdered, leading to the woman sinking into the clutches of alcoholism (1). Other stories depicting absinthe drinkers as hellbound creatures include the two tails by the The Goncourt brothers (5). Their first novel was Sister Philoméne (1861), which showcases how people turn to “the green fairy [for] the only moments of happiness, lightness, and a kind of intellectual sensuality” (3) they can rarely experience in their dismal lives. In their second story, Germinie Lacerteux (1865), the brothers describe the life of a young girl who falls prey to absinthe because it “allows her to forget the misfortunes of her life, to drown her shame, to kill her remorse” (2). Both of their stories discuss the usage of absinthe as a crutch to deal with the negative emotions of everyday life, continuing the myth of absinthe as an escape.

The curiosity surrounding absinthe has long been documented. French soldiers popularized it in the 1800s when they claimed it was the cure for malaria and dysentery (5). At first it was reserved for the bourgeoisie who gave it the nickname “green fairy” due to anise’s distinct color. Soon, demand for the drink grew, and manufactures were able to distill it for a cheaper price (4). Eventually, it became more prominent in France than wine, and the French brought it to New Orleans when they colonized America.

Soon after Absinthe became popular in The United States, the public associated it with madness and insanity. Religious and temperance groups identified it as a societal problem and sought to eradicate it (1). Newspapers drew a large profit by printing stories on the consequences of drinking. Jean Lanfray’s story solidified absinthe’s bad reputation. Under the influence of “The Evil Green Menace,” Lanfray murdered his wife after an argument (4). When their four-year-old daughter walked into the room she too was silenced with a bullet. The carnage did not stop there. Lanfray entered his sleeping two-year-old’s room and shot her too. He then attempted suicide with the rifle, but only wounded his jaw. Police found him passed out on the family’s farm, clutching the body of his two-year-old (4). Even though Lanfray drank mostly wine before he snapped, his murderous rage was blamed on the two glasses of absinthe he had to start his morning. After this story spread, absinthe was banned in numerous countries around the world including France and The United States (4), contributing further to its mythology.

by Krista Andreoni

Only in the late 1990s and early 2000s was absinthe allowed to return to the market. Scientists discovered that absinthe contained the chemical thujone, which caused seizures and hallucinations (4). However, the amount of thujone in the drink is so minute that under the Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau guidelines, there is technically no thujone in absinthe. This analysis, along with the popularity of the numerous myths surrounding the drink in the art and literature worlds, return absinthe’s popularity. Absinthe is alleged to increase perception and consciousness, leading to an increase in creativity (4). The crowd at the Old Absinthe House reflects the public’s desire for mind-altering experiences with a now-legal drug. Although it is scientifically impossible for them to have hallucinations from this absinthe, the patrons still let the good times roll. People try absinthe because they are attracted to the unknown. Tourists desire to experience the mystery of the untapped potential of the human mind, even if it is not scientifically accurate. I experienced the mystery for myself just by being present in this historic place and taking in the sounds.

This piece was completed for the class Alternative Journalism, which is taught by Kelley Crawford at Tulane University.

NOLAbeings

Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings

Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

Data corner: Adobe Suite (create a PDF, social media graphic, presentation, edit a photo and video

Data corner is where you go to work with analytics and top tech skills. It takes on everything from PERL and SQL to Canva and Sprout Social.

Data corner: Adobe Suite (create a PDF, social media graphic, presentation, edit a photo and video

Data corner is where you go to work with analytics and top tech skills. It takes on everything from PERL and SQL to Canva and Sprout Social.