Two years ago, a family friend of mine decided to move to New Orleans to work for an organization aimed at helping formerly incarcerated people and their families with reentry into society. This was a scary world he was entering, one that could cause a trepidacious existence. However, he was serving a higher purpose and a necessary presence in a broken system. Growing up in an upper-middle-class community, I had not been raised with crime and incarceration as a presence in my life. I learned about it in school, but I never knew someone who had been incarcerated, until one day a ride to the airport changed everything.

Heading to the airport to go home last year, I struck up a conversation with my Uber driver. I asked about his life and family, and he said that he had many family members and friends who were struggling due to either former or current incarceration. He said that many were still awaiting trial for nonviolent offenses; others could not find jobs due to their criminal record; and others simply did not know how to connect with their family upon their return. For my entire flight home, I had a pit in my stomach. I was raised in a liberal community that did not shy away from discussing social issues like racial inequality; but, it was a removed subject. None of us had experienced the tragedy of a loved one being imprisoned None of us have been profiled or stopped and frisked on the streets of Manhattan where I grew up because of what we wore or the color of our skin.

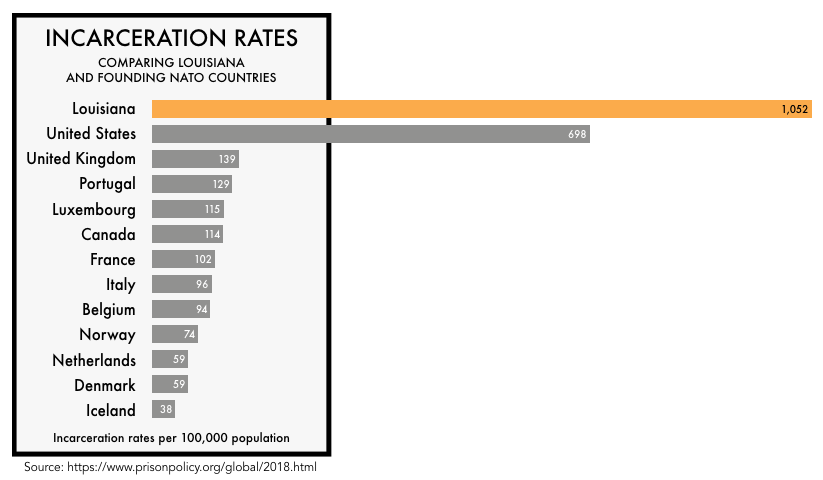

From Prison Policy Initiative: “In the U.S., incarceration extends beyond prisons and local jails to include other systems of confinement. The U.S. and state incarceration rates in this graph include people held by these other parts of the justice system, so they may be slightly higher than the commonly reported incarceration rates that only include prisons and jails. Details on the data are available in States of Incarceration: The Global Context.”

The stigma surrounding the formerly incarcerated is rampant, and Louisiana has one of the highest incarceration rates, not only in the country but in the world. Louisiana’s incarceration rate per 100,000 is 1,052, whereas the United States has a rate of 698 per 100,000 and other Nato countries such as the UK, Canada, France, and others have a rate of less than 200 per 100,000. Louisiana’s incarceration rate is higher than the US total and higher than other NATO countries. This is the startling reality of the prison system currently in place in Louisiana.

What is unsurprising, yet perpetually disturbing, is the vast racial inequality reflected in the incarceration rates in New Orleans and in Louisiana as a whole. In New Orleans, black men are 50% more likely to be arrested than white men. Black women are 55% more likely to be arrested than white women. This shows the incredible disparity amongst incarcerated individuals. According to a 2017 Prison Policy Initiative report, 2,749 black men per 100,000 were incarcerated, a stark contrast from the 675 white men per 100,000. Additionally, it was found in the same study that 48% of inmates were deemed low risk, but remained in prison because they could not afford the bond necessary to leave (Wilson et al. 2017). These shocking statistics are all indicative of the same problem: our justice system is not blind, it is the opposite. Our justice system disproportionately affects those of certain racial groups and income status, which are often connected for a myriad of structural reasons.

The impact of incarceration on inmates and their families does not end upon release. High recidivism rates in Louisiana show that the system is not effective. According to the Southern Poverty Law Center, 44.3% of people released from prison in Louisiana in 2011 had returned by 2016. The unemployment rate for formerly incarcerated people is over 27%. That is statistically higher than any historical period, even the Great Depression. The structural barriers to the formerly incarcerated make it incredibly difficult to find work and support a family. Without access to income, stability of a job or means for survival, it is no wonder the recidivism rate is so high. Many solutions have been proposed throughout New Orleans’ history, but few have had the success of reentry programs.

“Reentry” is the term used for the release of inmates from prison back to their communities. Many cities and states have adopted programs to help with this transition in the hopes that employment and stability will help reduce the chances of repeated offense. In Las Vegas, Nevada, the Hope for Prisoners reentry program has had incredible results, with 64% of participants finding employment after program completion, and only 6% of participants returning to prison [as opposed to the national average of 44%]. The program provides mentoring, job preparation, positive relationship building with law enforcement and vocational training. Having a positive relationship with law enforcement is a major victory for the program. Cities around the world have struggled to effectively investigate gun crimes due to poor community relations. With instances such as the deaths of Eric Garner and Michael Brown or policies where black men have been targeted such as stop and frisk, it is no secret that in low-income communities and predominantly black communities relationships with the police are strained. Hope for Prisoners, therefore, has worked to rebuild trust with these communities in an effort to move forward.

New Orleans has followed suit by adopting programs to help formerly incarcerated such as The First 72+ and VOTENOLA. The First 72+ is named for the first 72 hours upon release, which are known to be the most crucial indicator of success or return to prison. Located across from the Orleans Justice Center in Mid-City, the organization provides clothes, food, rides to social services and more during the first three days of release. After that, a transitional house located next door is available for six men at a time to provide ease in which to meet with case managers, mentors and other services. The program was founded by six men who each had personally experienced the Louisiana Justice System and had helped one another upon release. Having formerly incarcerated people as mentors is one of the unique components of The First 72+. It allows for participants to see the other side and the possibilities that await.

VOTENOLA is a policy-based organization aimed at reforming the justice system in New Orleans and granting rights to the formerly incarcerated. They have advocated for everything from housing and voting rights, to statewide reentry programming. This is incredibly important as the policies VOTENOLA fight for directly affect those who were formerly incarcerated and have the potential to make real change.

Reentry programs are showing real progress in reducing recidivism rates and helping the formerly incarcerated and their families to be successful and safe. VOTENOLA and the First 72+ are following in the steps of established programs like Hope for Prisoners, hoping to yield similar results. According to a study done by the University of Las Vegas Center for Crime and Justice Policy, the strongest indicator of Hope for Prisoners participant success was mentorship (Troyshinski et al. 2016). The First 72+ has taken this approach in New Orleans, focusing on mentorship and service providing to help the formerly incarcerated build their life out of prison. VOTENOLA goes one step higher but fighting for the rights of the formerly incarcerated and giving this marginalized group a seat at the table. Programs such as these are popping up around the country. Presidential candidates are recognizing their value. Perhaps the implementation of reentry programs on a larger scale would help rebuild the broken justice system of today.

Works Cited

NOLAbeings

Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings

Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

Data corner: Adobe Suite (create a PDF, social media graphic, presentation, edit a photo and video

Data corner is where you go to work with analytics and top tech skills. It takes on everything from PERL and SQL to Canva and Sprout Social.

Data corner: Adobe Suite (create a PDF, social media graphic, presentation, edit a photo and video

Data corner is where you go to work with analytics and top tech skills. It takes on everything from PERL and SQL to Canva and Sprout Social.