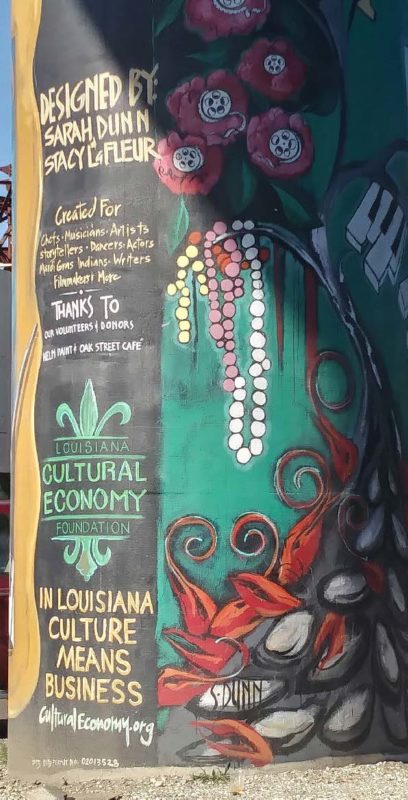

“Culture means business” mural near Interstate 10’s off-ramp on Poydras, the route many visitors take into New Orleans. Photograph by Kevin Korson.

Tourists are generally seen as invaders to a destination’s culture. Often portrayed as rude and dull, these visitors are openly disdained by most of the population outside of the tourism industry, and even mocked by those who work in the industry as being clueless. Tour guides fare even worse. We are wholly portrayed as dishonest purveyors of a culture, fabricating stories, and playing to the least common denominator in the tourism trade by plying other people’s neighborhoods and history into a for-profit endeavor.

It is not widely known that tour guides undergo extensive educational training in history and architecture, as well as field training on how to perform and lead a tour. Tour guides are central in perpetuating a city’s culture and economy to a broader, successful, and more sophisticated audience than is commonly assumed. Tourists can be informed patrons of a culture that most of the indigenous population either ignores or is unaware of; many small neighborhood museums are kept afloat by tourists because locals never visit them. This interactive set of dynamics between tourist participation and tour guide education and training is what keeps many cities functioning as traditional forums of commerce (manufacturing or natural resource exploitation) have disappeared in the present global economy. There are a fair number of charlatans, as in any industry, but the overall outcome far surpasses the detrimental aspects.

A Spin On My Origin Story

I immigrated to New Orleans from Los Angeles in 1994. I hail from the West Coast, so I’m neither Yankee nor Southerner. My teenaged parents, both from the Midwest but living in SoCal at the time, ran away and got married in Tijuana in the Spring of 1963, and I was born about nine months later. I asked my birth-mother, Veronica Boudreau, “You know what this means?”

She said, “Yes, we were young and in love.”

I said, “No, that makes me a Mexican.”

Veronica didn’t think this was very funny. Nor did she think my living in New Orleans was a good thing. Living in a roustabout port city full to the brim with scalawags and scoundrels is not everybody’s definition of a home. But I get it.

I appreciate the heavy drumming sounds of Mardi Gras thundering off her old brick buildings and funneling addictively through her antebellum mansions and oak lined Avenues like a war cry of youth come to the party. I appreciate the ultra-modern spaceship beauty of her Superdome, and the irony that she also looks like the world’s largest can of roll-on antiperspirant. I love that New Orleans can laugh at herself. Her people can laugh at their own foibles, especially when not laughing would only lead to tears. All those terrible Saints seasons, all those “pawkin’ tickets, dawlin.’ Somehow I understand all her bizarre accents. The smell of crawfish under your fingernails that no matter how hard you might try to wash away with soap lingers until late the next day. I identify with the quote, “I wasn’t born in New Orleans, but New Orleans was born in me.”

NOLAbeings

Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

NOLAbeings

Multimedia artist Claire Bangser created NOLAbeings as a portrait-based story project that marries...

Data corner: Adobe Suite (create a PDF, social media graphic, presentation, edit a photo and video

Data corner is where you go to work with analytics and top tech skills. It takes on everything from PERL and SQL to Canva and Sprout Social.

Data corner: Adobe Suite (create a PDF, social media graphic, presentation, edit a photo and video

Data corner is where you go to work with analytics and top tech skills. It takes on everything from PERL and SQL to Canva and Sprout Social.