I did an interview with my papa, whose name is Jack, and my grandmother, Barbara, in order to come back to my family’s Sicilian roots. The interview took place in their home in Kenner, which they have now lived in for roughly 20 years. Though the interview is focused on my papa, since he is the Sicilian one, my grandmother is heard throughout the interview as she has known my papa and his family for most of her life, and she reflects on the accuracy of the statements my papa makes.

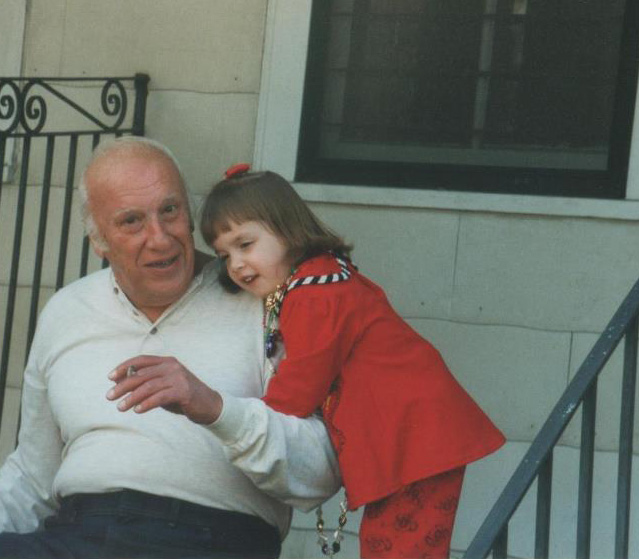

Lyndsey with her grandfather, Jack Pasternostro. Photograph courtesy of the Nuebel family.

Jack Paternostro: Our family first came to New Orleans around 1910. The Penninos are from Corleone and the Paternostros are from Palermo. Ok? That’s ya great-great-grandfathers. Both of em were beautiful.

Lyndsey: Do you know why they came to the United States?

Jack: Mussolini. Second World War. You know what I’m talkin’ about?

Barbara: Jack they didn’t come over during the Second World War! That was before the war right?

Jack: She studied that in school, man! Second World War…Mussolini was a dictator in Italy. Ya grandfathers’ had property over there alright? Grandfather Pennino had a bunch of stores. Mussolini took all the stores away. Grandpa Paternostro had vineyards. Mussolini took all that away. So both of em picked up their families. Grandpa Pennino’s family had my Uncle Frank and Aunt Rosie. They were already kids when they came over on a boat around 1910.

Barbara: They had your mother, too!

Jack: My motha’ wasn’t born in Italy! Geeze! She was born in the United States! [Laughs] Oh boy, you made me laugh, dahlin.

Barbara: Well, I’m glad.

Jack: Uncle Charlie, Uncle Joe, Uncle Ed, and my mama was born in the United States. Aight? Grandpa Paternostro came over on the same boat. Grandpa Pennino and Grandpa Pternostro were friends in Italy. So Grandpa Patty came over with Uncle Angelo and Aunt Lucy. They were two of the oldest ones. Now I’ll tell you the rest that were born. You want to know all that?

Lyndsey: Yeah!

Jack: Alright. On the Pennino side, it was Uncle Frank and Aunt Rosie who came over on the boat with his kids, and Uncle Joe, alright, one of your great uncles. And then… Uncle Eddy. And then Uncle Charlie and then your Maw-Maw Mary was the youngest one. Your Uncle Sal was in the Second World War. He was the only one that went to Germany. The reason why my daddy and all my uncles came over to New Orleans was because of the Higgins shipyard and built the PT boats and the landing barges.

Barbara: His daddy’s name was John by the way.

Jack: What?

Barbara: Ya daddy’s name is John; she didn’t know your dad!

Jack: I know that!

Barbara: I’ll be quiet.

Jack: Your other uncle was Uncle Sam, alright? He helped build the Panama Canal. You know about that, huh? They’re all Italian, baby, that’s what I am talking about. You gotta great history. Alright, after the Second World War, my daddy, your great-grandfather and the rest of em tried to go back to Italy, alright? They didn’t make it. They tried to get in touch with certain people over there about their property, before Mussolini took it over. All the papers, all the documents, were burned. They had all kinda property, baby. They couldn’t find nothing so my grandfather Pennino started buying up property. He had a real estate business [in] New Orleans. He owned the whole block he lived on, baby.

Lyndsey: What block did he live in?

Jack: 2300 block of Ursulines.

Lyndsey: So is that where they moved to whenever they came from Italy?

Jack: Right on Ursulines. Grandpa Pennino bought a lot and built a chicken house where he had about 75 chickens. In the front, all of that was screened off. In the back, he had vegetables, raised corn, and all kinda stuff. I used to go back there as a kid and pick tomatoes and walk in the chicken shit! My cousin was Joycelyn, and we were raised up together. She wouldn’t go over there, man. She would say, “I’m not goin’ over there by those stinkin’ chickens!” Grandpa Paternostro went across the river to Marrero, and he owned a farm. Your great-great-grandfather had cows and everything else.

Lyndsey: So Pennino, he was a pretty good entrepreneur, and he had a lot of money. He was doing well. But in those days, weren’t Italians racially discriminated against? Do you know if he faced any racial discrimination?

Jack: Oh, no!

Barbara: Oh, nooo! He was a short, little old man who demanded respect. He wasn’t ugly, he was very kind, but you knew when you spoke to him, he commanded your respect. As a matter of fact, I’m gonna tell you something. When Papa was in the service, I was so scared and I didn’t know what to do. I didn’t have any money. We were young, young people. So he said I could go visit Papa in Texas, but I didn’t have any money. Maw Maw Audrey didn’t have any money. Papa said, ‘Go and ask my father for some money to get on a train and to come see me.’ He used to call me Baba which meant stupid [Laughs].

Jack: He couldn’t say Barbara. He was trying to say Barbara but all he could say was Baba!

Barbara: I said, ‘Jack wants me to come visit him but I don’t have any money for plane-fare. He said to ask if I could borrow money from you.’ And he said to me, ‘I will give you the money to go see him, but you have to pay me back.’ And I did! Because I was afraid! And he was just this little bitty man, but he said you have to pay me back!

Jack: He could be the godfather! All the houses that his kids had, including your great-grandmother’s, he bought them all houses. But, the same thing! They had to pay him back! See what I mean?

Waves of Change–The Impact of Political Tides on Louisiana’s Environmental Future

Healthy Gulf has been a cornerstone in safeguarding Louisiana’s natural and human resources through sustainable and equitable practices. But a new threat looms with Governor Jeff Landry’s recent consolidation proposal, which aims to merge crucial coastal management with the Department of Energy and Natural Resources. Writer Leah Claman delves into the complexities of this proposal, breaking it down for those unfamiliar with environmental policy, and sheds light on what this could mean for the future of Louisiana’s coast and its communities.

Waves of Change–The Impact of Political Tides on Louisiana’s Environmental Future

Healthy Gulf has been a cornerstone in safeguarding Louisiana’s natural and human resources through sustainable and equitable practices. But a new threat looms with Governor Jeff Landry’s recent consolidation proposal, which aims to merge crucial coastal management with the Department of Energy and Natural Resources. Writer Leah Claman delves into the complexities of this proposal, breaking it down for those unfamiliar with environmental policy, and sheds light on what this could mean for the future of Louisiana’s coast and its communities.

Earthtalk: Retaining starts with repurposing – Green Light New Orleans

This piece spotlights Green Light New Orleans, a non-profit dedicated to promoting collective engagement in sustainability practices in local households. Author Brett Steinberg discusses the non-profit's Rain Barrel program, effectively combining art and water conservation.

Earthtalk: Retaining starts with repurposing – Green Light New Orleans

This piece spotlights Green Light New Orleans, a non-profit dedicated to promoting collective engagement in sustainability practices in local households. Author Brett Steinberg discusses the non-profit's Rain Barrel program, effectively combining art and water conservation.