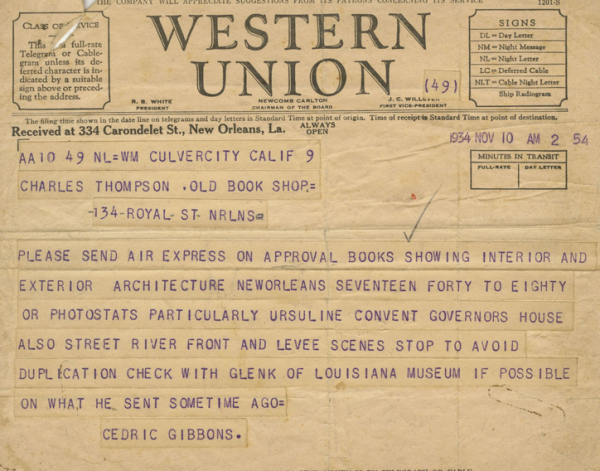

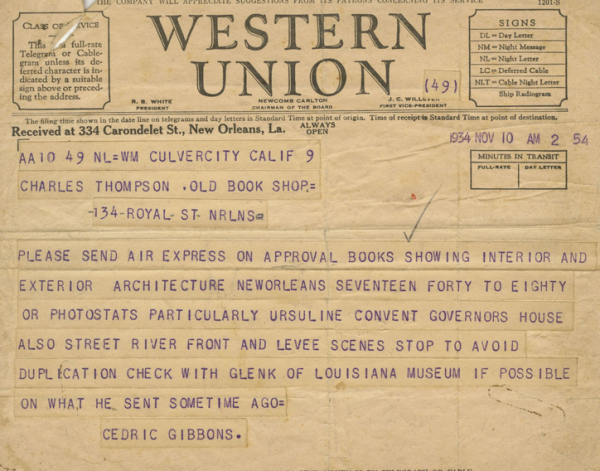

Western Union Telegram from Cedric Gibbons to Charles Johnson. From the Kuntz Collection at Tulane University.

Some may scoff at the idea of bookclubs, seeing them as social circles that gossip more than they discuss literature, but the book club concept is one that has sparked and fostered literary and political revolutions. For New Orleans, book clubs in the late 19th and early 20th century (although they were called “salons” in that age) had revolution written all over them.

Between 1900-1950, a literary renaissance emerged in New Orleans. This renaissance brought different literary themes that contrasted with the South’s old romantic view of the Confederacy conveyed in literature. Hmmm…removing and replacing iconized figures that praise the Confederacy. Sounds familiar.

With the literary renaissance, authors such as William Faulkner and Tennessee Williams came to New Orleans and their work here put them into the American literary spotlight. These authors challenged critics of Southern literature, such as H.L. Mencken, and by highlighting New Orleans on the literary map, more authors started traveling and living here. Inevitably, this changed the literary culture of New Orleans, and also the South in general. But, before we get to that happy, artistic ending, we need to start at the beginning.

After the Civil War, many southerners were devastated by the defeat of the Confederacy. The topic that dominated Southern literature at this time was the South’s “Lost Cause,” which glorified the Confederate Army and the way of living in the Antebellum Period. Northerners criticized the South by believing the South had narrow-minded literature and a lack of education. However, some literature from the Reconstruction helped spark a literary Renaissance in the South in the beginning of the 20th century.

During Reconstruction, well-known authors such as George Washington Cable, Grace King, Mark Twain and Kate Chopin contributed to the evolving literary culture. This change in book culture is present in the early to middle 20th century history of New Orleans. Specifically in New Orleans, George Washington Cable is attributed to the “city’s first literary light” by writing about his progressive stance on civil rights and American race relations (1).

During this Literary Renaissance, Southern authors commonly wrote about and lived in New Orleans since the exotic culture of New Orleans, cheap housing, and literary network appealed to many of them. Publishing companies and literary salons were also prominent in New Orleans during the 20th century. Since the literary culture was so rich, many people from all over the world contacted local bookstores for books and literary information, especially by Hollywood filmmakers. The 1880s and 1890s is when literary lovers and writers flocked to New Orleans because of the “decayed elegance, live music, friendly watering holes, literary salons, and literary festivals.” (2)

The city began to be nicknamed “Greenwich Village South” due to its uniqueness. Many authors who once lived in New Orleans during this time became nationally recognized for his or her work. These authors challenged the stereotype of Southern literature, such as George Washington Cable, who was born in New Orleans in 1844 and is often viewed as the founder of this Southern renaissance. Cable was a columnist and reporter for The Picayune. His first literary works are about creole life since he studied New Orleans colonial history and thought that it was “a pity for the stuff to go so to waste” (3).

Cable wrote the book The Grandissimes in 1880. The content of the book dealt with racial injustice and multiracial families. Therefore, it is considered to be the first modern Southern novel by many because The Grandissimes was one of the first Southern novels that criticized the racial inequality of the South. Cable gave well-received public readings in New Orleans in 1884 and used his home at 1313 Eighth Street as a literary salon to entertain other Southern writers. However, when the South became increasingly democratic, hostility was directed straight at Cable. Therefore, in 1885, Cable and his family moved from New Orleans to Northampton, Massachusetts. Yet, he had helped lay the land for writers like Grace King, William Faulkner, Tennesse Williams, and Lyle Saxon, who worked for the Item and the Times-Picayune.

He wrote many books involving New Orleans such as Fabulous New Orleans, Old Louisiana and Lafitte the Pirate. Fabulous New Orleans describes an afternoon stroll in the French Quarter. Saxon became known as “Mr. French Quarter” for restoring houses at 536 and 612 Royal Street (4).

He used these residences as literary salons in the 1930s and entertained guests such as William Faulkner and Sherwood Anderson. He also bought an apartment at the St. Charles hotel during the 1930s where he had another literary salon. In 1926, he won the O. Henry Award Prize.

All of these literary figures helped establish a platform or resistance, change, and ingenuity, and it was all taking place in New Orleans. It wasn’t just the books these authors wrote, though, that vibrantly charged New Orleans with literary electricity. It was also the magazines, and that’s what will get to next time. For now, maybe it’s time to sign up for that book club, or maybe change the name to salon.

Sources:

1 Jeff Weddle, In Bohemian New Orleans: The Story of The Outsider and Loujon Press Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2007 25.0.

2 Patricia Brady, introduction to Literary New Orleans Atlanta: Hill Street Press, 1999 VII–XII.

3 Judy Long, “George Washington Cable” in Literary New Orleans Athens: Hill Street Press, 1999 45.

4 Judy Long, “Lyle Saxon” in Literary New Orleans Athens: Hill Street Press, 1999 115.

The full article was originally published on February 6, 2015. It has been edited, and for a full view of the 2015 article, click here.